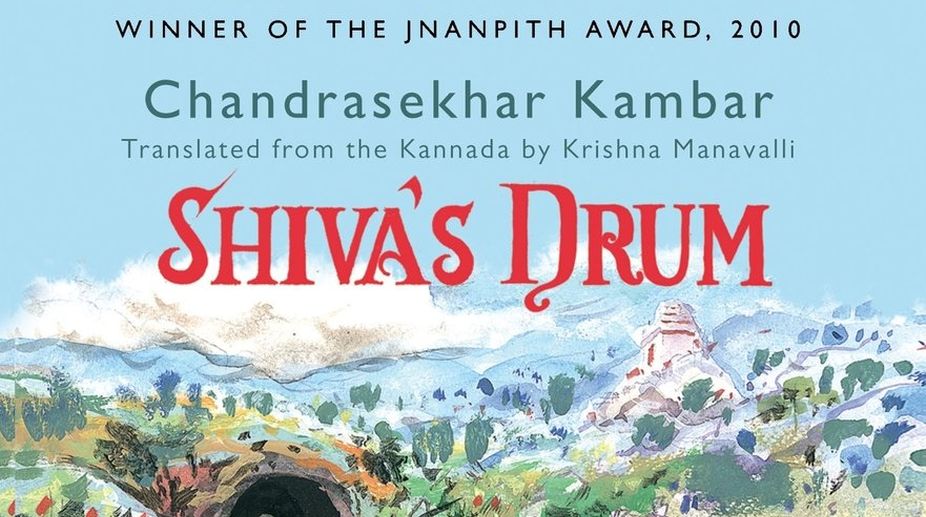

This is the story of the slow growth of a village on the path of progress. Set in Shivapura, a village that is tranquil and beautiful, the story becomes something of the dark tragedy of our modern times.

Chandrashekhar Kambar, with the help of his translator, has managed to pull off the duality between contentment with the present and a desire for progress and quick wealth.

Advertisement

Village life is slow, dictated by the cycle of the seasons. Shivapura’s chief Baramegowda feels that life could be even better and allows outsiders into the village, with the approval of the local powers that be.

He signs over land for a modern school and college, encroaching on the waters of the lake. Industry springs up and the pristine Mallimadu waters are polluted while the fruit trees are poisoned.

Kambar gives weight to the physical beauty of the village, saving his famed poetry for the description of a Shivapura that has appeared in his other writings as a place out of folklore rather than an actual living village. This makes the wanton destruction more credible to those familiar with his work.

The situation calls for a hero and Chambasa with his sinewy shoulders is the only force strong enough to lead the Dalit farmers — who are part of the fallout when political greed makes its presence felt — in a fight to save the village and a way of life that was once idyllic.

Chambasa understands what is good about modernity and what is necessary to bring balance and profitability to the village. He is an almost mythological figure who rises over what today’s world would call handicaps — his marriage to a Devadasi, a physically challenged daughter and the fact that he was a chief’s son but was nursed by a low caste woman which is why his uncle is now village chief and cause of the village’s woes.

Kambar refers to the chief Baramegowda as a cripple, juxtaposing his deformity against that of Chambasa’s daughter’s, though it might be mentioned that cripple is an insult frequently thrown around in many cultures and that cripples are usually villains.

Shiva’s Drum is deeply layered and each of the plots has its own back-story that requires patient comprehension on the reader’s part. The fairytale ending may also seem a little improbable given the direction of the plot and the fact that by the end of the story Baramegowda is beginning to realise that he has made a mistake and that an excessive love of money and flesh sow the seeds of their own downfall. It could have been a tale of hubris repented too late rather than one of love saving the day.

Eighty-year-old Kambar is aware of the forces at work in modern India and the fact that feudal hierarchies can be and are exploited. The result is a world filled with violence where women are the ones who suffer most.

Not that he gives his women characters much depth since they are just characters in his morality tale. His characters, for the most part are confused, feeling that they are missing out on something that the rest of the country enjoys but at the same time, reluctant to move on.

In the end, Shiva’s Drum has to be accepted as just that. Kambar implies that Shivapura’s is the fate awaiting societies that are ruled by greed rather than ethics but purity of motive can be a light at the end of the tunnel.

The reviewer is a freelance contributor