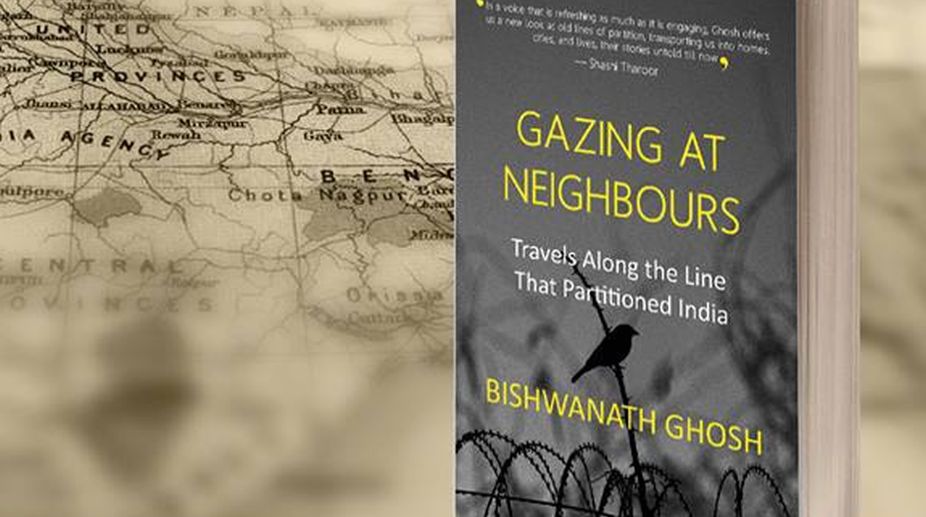

Gazing at Neighbours delves deep into the lives of people living along the border, what is populary known as the Radcliffe Line, and sheds light on many untold stories. A review by Nivedita R

Enough has been written and re-written about Partition of India and the horrors associated with it. The mere word, Partition, evokes lot of emotions that have been engraved deep in our hearts.

Advertisement

Although we already know a lot about how Partition of India happened and the history behind it, we almost fail to reminisce about the lives of people on the border along the Radcliffe Line.

What is shocking to know is that, in mere five weeks the fate of our country was decided, changing the lives of millions of people forever.

Millions died and most of them got displaced. What is Radcliffe Line? “No other seemingly benign exercise has such farreaching consequences as drawing a line on a map. On the face of it, you merely put pencil to a paper, but the line actually runs through towns, villages, valleys, farmlands, forests, rivers, ponds and people,” articulated the author of Gazing at Neighbours, Bishwanath Ghosh. The book takes the readers through the lives of people on the border and sheds light on the history of Radcliffe Line.

The author explains, “In July 1947, British barrister Cyril Radcliffe was summoned to New Delhi and given five weeks to draw, on the map of the subcontinent, two zigzagged lines that would decide the future of one-fifth of the human race.

One line, 553 km long, created the province of West Punjab, the other, adding up to 4,096 km, carved out a province called East Bengal. Both territories joined the new-born nation of Pakistan ~ an event called the Partition of India, which saw one million people being butchered and another 15 million uprooted from their homes.” Seventy years have gone by and yet the scars of Partition linger on our hearts and minds.

The resentment for the refugees has rather increased over the years. The bitter-sweet relationship of India and Pakistan is there for everyone to see. Speaking about the role of Mahatma Gandhi in Partition, Ghosh says, “Many in India, even today, thoughtlessly blame Gandhi for Partition, the charge against him being that he did not stop it.

The truth is that Gandhi had very little say in the months leading to Partition, when the political landscape was dominated by Nehru and Jinnah, the public faces, respectively, of the Congress and the Muslim League.”

Elucidating further, the author writes, “Most refugees who went through the horrors of Partition as adults have passed on. The succeeding generations have long grown roots in India. The surgical scars, however, remain and will remain as long as India, Pakistan and Bangladesh exist as separate countries. The scars, considered together, are called the Radcliffe Line. In the places it runs through, the line is referred to variously as zero line, boundary line, international border or simply border. Here, barbed wires have split families; concrete pillars have turned neighbours into foreigners; people follow restrictions, which their countrymen elsewhere don’t, and wish sometimes silently, and sometimes aloud, that the line did not exist.”

Renowned for his literary travelogues, Ghosh meanders along the Radcliffe line, and with an interesting narrative, he takes us through the vibrant greenery of Punjab as well as the more melancholic landscape of the states surrounding Bangladesh, and examines first hand, life on the border.

The lucid vocabulary keeps the readers engrossed till the end and the plot rekindles our memories of dreadful times during Partition of India.

In all, this book narrates myriad of untold stories from the times of Partition that is thought-provoking and refreshing.