Hamas frees eight hostages in Gaza; Israel delays prisoner release

Palestinian militants in Gaza, led by Hamas, released eight hostages, three Israelis and five Thais, on Thursday.

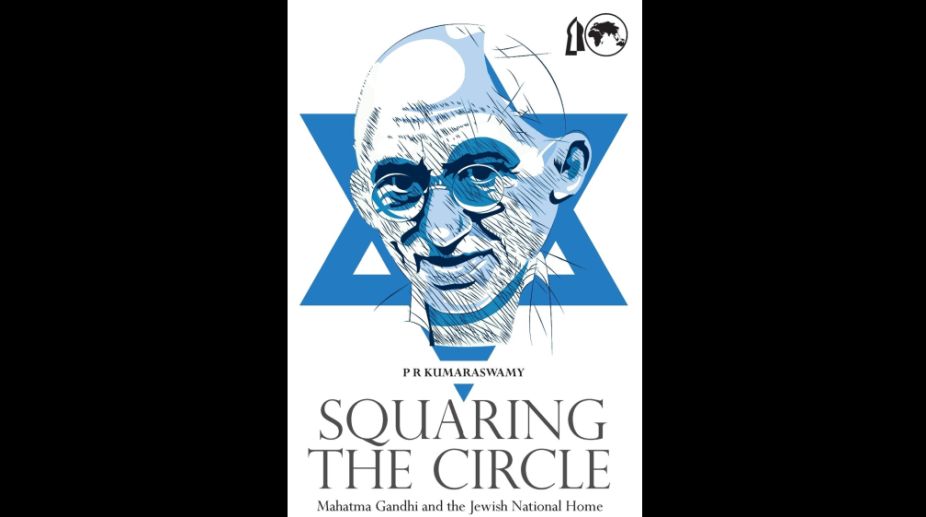

This book is timely; it coincides with the hundredth anniversary of the Balfour Declaration. Kumaraswamy is the leading Indian specialist on Israel and a robust advocate of that nation. He has done great service in this book by positioning the Zionist struggle in the relevant Indian political context, and by exposing Gandhi’s inconsistencies in his approach to the creation of Israel and the related issue of non-violence. A serious charge against Gandhi is one of cover-up: there are omissions about Israel in the Gandhi Collected Works and evidence points to Pyarelal as the culprit.

In his writings, Gandhi made more references to Jews than their small number in India would justify; he made fewer references to Sikhs and Buddhists. But he opposed the Zionist objective of a Jewish national home in Palestine, and could not accept Jewish use of violence in seeking that home. He also disproved of Jewish collaboration with British imperialism to achieve Zionist goals, but his knowledge was incomplete and heavily influenced by the domestic situation, which explains Gandhi’s acceptance of the Khilafat cause and his continuous appeasement of Muslims, whom he hoped to enlist for the freedom movement.

Advertisement

During the Khilafat phase of the 1920s, Gandhi accepted Palestine as part of the Jazirat ulArab (undefined but interpreted by Gandhi as the Arab peninsula) which had to remain under Islamic sovereignty according to the “injunction” of Prophet Mohammed, an assertion that ignored the Jewish and Christian holy sites in Palestine. He viewed Judaism through Christian anti-Semitic lens, and Zionism through a Muslim prism. Indian Muslims were then the largest such community in the world and Gandhi sheltered behind them to avoid a positive stand on Israel. His appeal for Jewish-Arab cooperation and for the Jews to rely on the goodwill of the Arabs, though “no exception can possibly be taken to the natural desire of the Jews to found a home in Palestine,” was as unavailing as his hopes of Congress-Muslim League (ML) cooperation. In his gloss over Jewish suffering in World War II he set a bad example for Nehru and Bose.

Advertisement

In the 1930s Palestine became a contested question between the Congress and the ML. Congress sought to wrest the leadership of the Muslims from Jinnah, who opposed British imperialism while depending on the British against the Congress. Riposting to ML’s marking Palestine Day since 1930, Congress followed suit in 1936. Gandhi’s “offer to assist in bringing about a settlement” through Arab-Jewish accommodation, of which no details are forthcoming other than the Zionist refusal to seek accommodation with the Palestinian Arabs, failed. He viewed Zionism as a spiritual aspiration not germane for the reoccupation of Palestine, and least of all for the Jewish return to be achieved through force or collaboration with the British. The Zionists reached out to Gandhi in the 1930s to separate the homeland issue from Indian domestic politics and gain his favourable opinion, but they were unable to empathise with his liberation movement from the British since they were dependent on the goodwill of the Palestine Mandate authorities.

In later life, in 1946, Gandhi accepted that the Jews had a good case, and even a prior claim on Palestine, but echoing the Balfour declaration, he hoped that the Arabs would not be wronged. His most sympathetic opinion was in April 1947, but it was too little too late, when “all sides ignored the nuanced shift.” Even this shift was linked to the Jews adopting non-violence — an attitude he never urged on the Arabs or Khilafat leaders — and his appeal to Indians not to volunteer for the British army was ignored.

Gandhi’s stance created a “predisposed anti-Israeli position.” In 1903, 1932 and 1938 he drew parallels between the European treatment of Jews and the untouchables’ plight in India. His “sympathy for the plight of Jews in Nazi Germany was visible, but insufficient to link it to the Jewish desire for self-determination,” and his Harijan article of 1938 on the Jews led to a breakdown of contact with the Zionists.

Gandhi’s understanding of Judaism was more limited and prejudiced than his understanding of the other Abrahamic faiths of Islam and Christianity. For him, Zionist claims to Palestine were a “Biblical conception” and not geographical, though he did not use the same yardstick of a spiritual or abstract space for Palestinian Muslims. As the author writes, “Zionism was un-Gandhian in the sense that it was not utopian.” Gandhi failed to note that Zionism transformed Jews into a community in the national sense, a distinct nation like the distinct Muslim nationalist consciousness that paved the way to Pakistan. Both Zionism and the ML stood for religious nationalism and the Jewish demand for a homeland was no different from the ML’s demand for Pakistan. Gandhi was perhaps consistent in opposing the religion-based nationalism of both the ML and the Zionists, which ran counter to Congress’ territorial secular nationalism.

It is not churlish to mention that this otherwise penetrating book suffers from deficiencies. Due to the thematic format beloved of academics, there are innumerable repetitions, though a chronological, primarily historical, account would have served better. Another vexation is the needless numbering of arguments, reminiscent of pedagogical lecture notes. There are nine such “points” in chapter 10 and 12 in chapter 11. The author is prone to rhetorically use multiple descriptors; thus, “controversial, problematic, hypocritical and even selective,” and just two lines further down, “politically naïve, morally inadequate and even simplistic.”

It is not clear, when Kumaraswamy discusses Gandhi’s Jewish friendships, why he should expect anyone to share the views of his/her friends. There are misleading statements such as “The Holy Land, especially Jerusalem … was now promised to the Jews through the Balfour declaration,” and hyperbole, namely “When it comes to Israel, Palestine or the wider Middle East, Mahatma Gandhi enjoys near universal veneration.” The Jews text covers four and half pages and should have been given as an annexure. So too should the Balfour Declaration.

Gandhi cannot be wholly blamed for lack of knowledge and comprehension; the same applies to all in public life who can bestow limited attention to complex international issues. But he is rightly accused of deviousness, pontificating and assumption of moral superiority — “my opinion is based on ethical considerations…independent of results.” Saints are consistent; politicians are not. Gandhi was “an astute political leader” anxious to incorporate Indian Muslims in his movement. He plunged the Congress into the Khilafat cause to out-Islamize the Muslims thereby involving Indian Islam in the Middle East. Gandhi’s advice to Jews not to collaborate with imperialists did not apply to Bose’s alliance with the Nazis and Japan, and he later concurred that force was needed by the Indian state to repel Pakistani infiltration in Kashmir. Kumaraswamy subjects the sainted Gandhi to valid criticism for the opinions he expounds despite insufficient understanding, and lack of transparency. Gandhi’s plea for non-violence against the Nazis was nonsensical, and he did not urge this on the Arabs.

Available documents throw no light on Gandhi’s views on India’s federal, as opposed to the UN’s partition, plan of 1947. Adverting to the title of this book, is it possible to reconcile Gandhi’s opposition to Jewish nationalism with India’s new-minted friendship with Israel? India’s belated decision was motivated by several factors, none of which had anything to do with Gandhi. Consequently, as Kumaraswamy correctly states, squaring the circle “is a futile exercise.”

The reviewer is India’s former Foreign Secretary

Advertisement