Palamau tigers head for home: Foresters

It's possibly the time for the Jharkhand tigers to return home, as their current movement reflects.

It was more than 48 hours since the huge animals had wandered onto the doorstep of Kolkata and tranquilisers, flames and skills used to sedate and pack them off to their new home. Here’s a first person account of every bit of the action

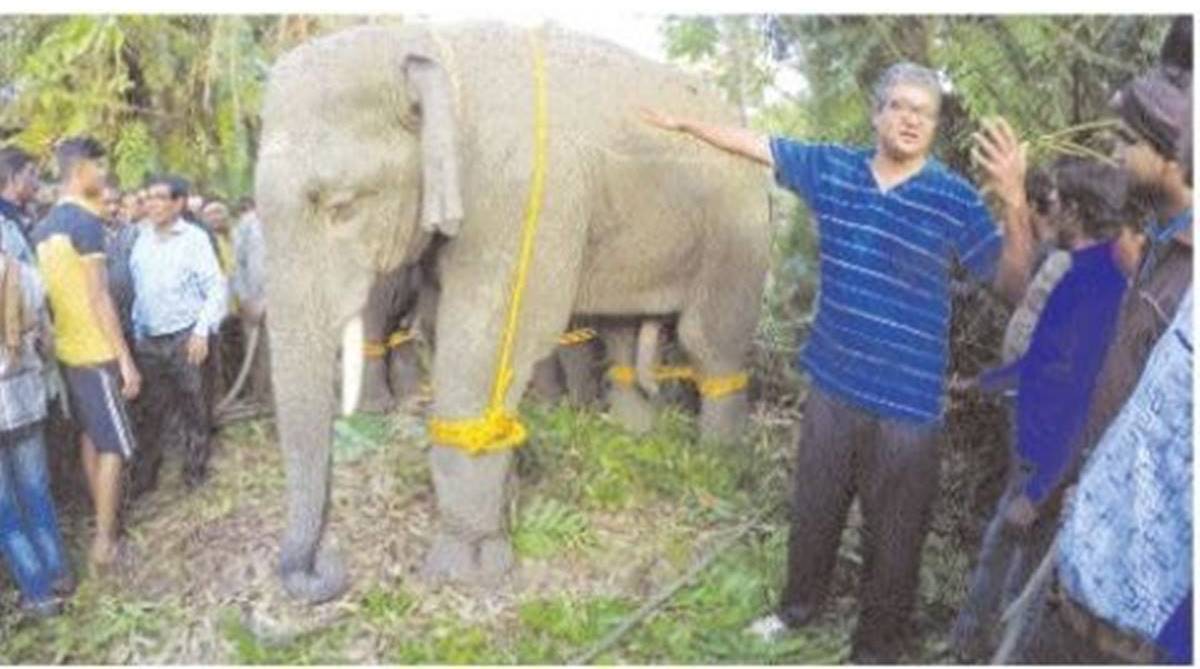

The frequency of elephant-man conflict in that district is much greater than in Howrah . (SNS Photo)

I am an early riser but even for me the ‘ping!’ of a WhatsApp message at 6 in the morning was unusual. “Haati dhukeyche,” said my friend from Howrah. It was Monday, 11 February – and that was not how I was expecting to start the week. Ninety minutes later I was there. Uttar Bhatora is an island near the confluence of the Rupnarayan and Mundeswari rivers, about 60 km from Kolkata. The bamboo bridge creaked and shook as I drove my car over it. But I wasn’t paying attention to those noises – there was a huge gathering of villagers that I was focused on. Behind them were the two elephants that had wandered into the area during the night.

They seemed to be protecting each other. Standing side-by-side in the bamboo grove, the sub-adult males were clearly under stress – tails stiff, a mock charge and then a retreat. Officials of the Forest Department, Police and Civil Defence were doing their best to manage the crowd while they waited for the “hullah party” to arrive from West Midnapore. As the word suggests, the hullah party is literally a group of people who are yellers – except that there is a method to their shouting. The group works in a planned manner so that the object of the noise created by them is frightened into moving in a desired direction.

Advertisement

This takes some skill and that was the reason the party had to be called in from West Midnapore. The frequency of elephant-man conflict in that district is much greater than in Howrah and that makes the yellers much more experienced.

Advertisement

While yelling, these teams also hold up flaming torches, an improvement over the earlier practice of throwing fireballs at the poor animals. This change, incidentally, came about because of a public interest litigation filed by the wildlife author and activist, Prerna Bindra.

It was almost 3pm by the time the hullah party arrived. The elephants, in the meantime, had stayed in the bamboo grove, occasionally serving as backdrop for the selfie-seeking crowds. Some had come from as much as 30 km away.

The women were lipstick-ready for excitement. The presence of the author seemed to provide some assistance to the local authorities because of my past experience with handling mobs during tribal hunts. The team agreed that our attempt should be to drive the elephants toward Chandrakona, about 20 km away. As we moved in, the elephants responded and raised our hopes.

But after they had walked a while, we saw that they had just made a wide circle – and come back to exactly the spot we had started. And this happened a second time. It was almost as if the two had decided that the bamboo grove was a nice sanctuary and they would like to stay on. Three hours later, with the flaming torches having to be lit again and again, we were still there.

Finally, on the third attempt, we seem to have communicated our intentions well and the elephants moved away into the forest area where we were trying to push them. Tired but excited and satisfied, I returned home late that night. The poor, frightened animals also were heading home.

It was not to be. At 2 am the next morning, the Howrah friend was back on the phone – the elephants had been spotted swimming across the river, coming back toward where they had spent the past 24 hours.

This time it wasn’t the bamboo grove, but a banana plantation in Manikpir, near Ranihati, about 25 km from the bank of the Hooghly at Kolkata. The plantation was part of a wetland complex, with ponds, marshland, hogla and human habitation. It was 8 in the morning and, clearly, hullah parties were not going to work. Besides the futility of flaming torches in the daytime, the crowds were getting larger – even the Rapid Action Force had been summoned. This was when the Principal Chief Conservator of Forest decided that it was time to call for tranquilisers. Shooting tranquilisers at any wildlife is very tricky business. Not only does the dosage have to be expertly estimated based on the weight of the animal, the dart cannot land just anywhere on the body. Temple and stomach are strictly off limits and the shoulder is best. The rifle is a modified airgun with a pellet pushing the dart on which the tranquiliser is loaded. But because the dart is feathered, the trajectory may get erratic and, therefore, a calculated shooting distance is needed.

And, of course, the animal must stand still. The first tranquiliser was fired at about 1130 am. The elephants, both stung by the darts, reacted as expected they charged in the direction of the assaulters. I remembered the golden rule I had been taught when running in such terrain – take high steps, so you don’t get your feet entangled in the vines running on the ground. As it is, an elephant, at an hourly speed of 50 km, can easily outrun an average human; getting caught in the undergrowth is a sure way of being trampled upon. Fortunately, I could jump into a pond and did not have to test my speed against that of the two elephants. Later in the afternoon, by when more tranquiliser teams had assembled, I witnessed what could have been a highrisk situation. With four teams taking shots at the same targets, I suddenly realised that if more than one dart lands, we could have an overdosed pair of animals on our hands. Why isn’t there coordination or one control point so that this risk is reduced, I wondered.

But the elephants were in luck. Although bleeding spots suggested that each had been darted thrice, they did not seem to suffer from excessive dosage. Displaying amazing motor skills with their trunks, they managed to get the darts out but not before the medicine had started working. In fact, as we heard their snores after a while, I gathered enough courage to walk up and actually touch one of those beautiful creatures!

Now it was time for speedy action.

The legs of each elephant were tied together as they slept standing up. As the tranquiliser wore off, additional drugs were administered. A temporary road had been built to enable the tractor and trailer to come into the wetland area. Harnesses were put around them and a hydra lifted them on to the trailer. The 3-tonne weight of the elephant was no trouble at all for the 14-ton capacity hydra.

So, dosing in a half-sitting position, the elephants left on the morning of the 13th for Purulia. More than 48 hours after having wandered onto the doorstep of Kolkata, they were heading for the elephant reserve in Moyurjharna, on the Bengal-Jharkhand border, their new home.

You can be sure I will be going back to see them!

Advertisement