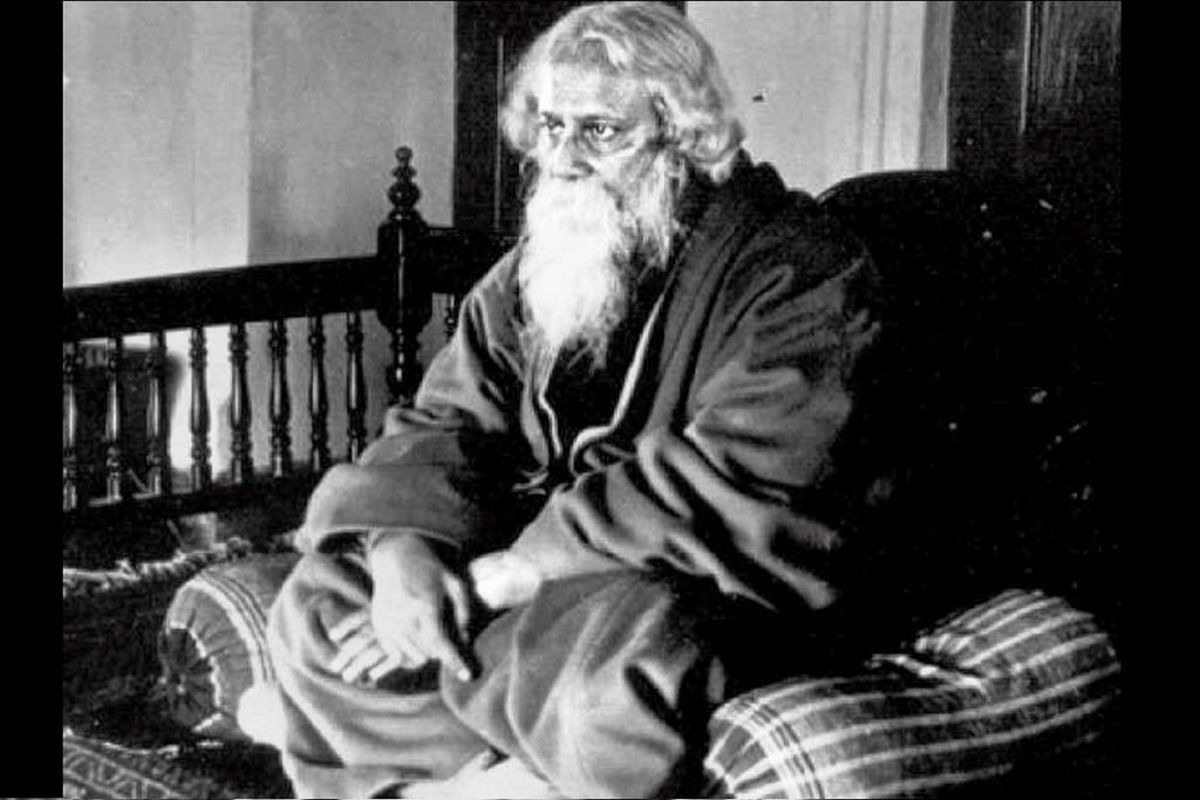

As is well-known, due to unavoidable circumstances Rabindranath Tagore could not attend the Nobel Award Ceremony held in Sweden in 1913. Instead, the telegram from Rabindranath Tagore, read by Mr. Clive, British Chargé affairs’, at the Nobel Banquet at Grand Hôtel, Stockholm, on 10 December 1913 stated, “I beg to convey to the Swedish Academy my grateful appreciation of the breadth of understanding which has brought the distant near, and has made a stranger a brother”. In 1913, Tagore proved that he could not only create literature in the colonizer’s language, English, but even secure the western world’s most coveted prize, the Nobel Prize for literature.

Simultaneously Tagore untiringly continued to write in his own indigenous language, Bengali, with equal felicity. I would urge you to notice that throughout his literary career Tagore did not compromise on the writer’s vision and ideology, under either local or global coercion, irrespective of his choice of language as a medium of communication and cultural connectivity. Eventually, in his Nobel Prize Acceptance speech delivered on 26 May 1921, eight years after he received the award in 1913, Tagore had observed with deference, “After my Gitanjali poems had been written in Bengali I translated those poems into English, without having any desire to have them published, being diffident of my mastery of that language, but I had the manuscript with me when I came to the west… I was accepted and the heart of the West opened without delay (Tagore 294).”

Advertisement

Interestingly, when the poet TS Eliot was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1948, though he wrote in English, Eliot foregrounded the importance of cultural transfer through poetry and language. So Eliot stated in his Nobel Prize acceptance speech, “To enjoy poetry belonging to another language, is to enjoy an understanding of the people to whom that language belongs, an understanding we can get in no other way. … And I take the award of the Nobel Prize in Literature, when it is given to a poet, to be primarily an assertion of the supra-national value of poetry”. So we notice that the first initiative in terms of reaching out to a global readership came from Tagore himself when in 1912, he translated his poems into English and handed over a copy of the translated poems to his friend William Rothenstein. Soon after, Tagore and the renowned Irish poet W B Yeats met for the first time on 27 June 1912, at the home of Rothenstein.

had previously sent Yeats the manuscripts of Tagore’s partial translation of Gitanjali. On July 7, Yeats gave a reading of these poems to a group of thrilled London literary elite, including Ernest Rhys and Ezra Pound. A member of the audience, May Sinclair, wrote a letter of effusive appreciation to Tagore. This letter has been mentioned by Bashabi Fraser in her latest biography of Tagore published in 2019. May Sinclair stated, “You have put into English which is absolutely transparent in its perfection things it is despaired of ever seeing written in English at all or in any Western language.” (Fraser 122) Tagore’s translated poems, typed and circulated by Rothenstein, were widely appreciated by the literati of London in 1912. Yeats hosted a dinner in honour of Tagore at the Trocadero restaurant in London on July 12.

While proposing a toast to honour Tagore, Yeats said, “To take part in honouring Mr Rabindranath Tagore, is one of the great events in my artistic life. (I have been carrying about with me a book of translations into English prose of a 100 of his Bengali lyrics, written within the last ten years.) I know of no man in my time who has done anything in the English language to equal these lyrics. Even as I read them in English in this literal prose translation, they are exquisite in style as in thought”. Tagore responded to Yeats by stating, “This is one of the proudest moments of my life. I have a speaking acquaintance with your glorious language; yet I can feel it in my own. My Bengali has been a jealous mistress, claiming all my homage and resenting rivals. Still I have put up with her exactions with cheerful submission; I could do no other.

(I cannot do more than assure you that the unfailing kindness with which I have been greeted in England has moved me far more than I can tell.) I have learned that, though our tongues are different and our habits dissimilar, at the bottom, our hearts are one. The monsoon clouds generated on the banks of the Nile, fertilize the far distant shores of the Ganges; ideas may have to cross from East to Western shores to find a welcome in men’s hearts and fulfil their promise. East is East and West is West ~ God forbid that it should be otherwise ~ but the twain must meet in amity, peace and understanding; their meeting will be all the more fruitful because of their differences; it must lead both to holy wedlock before the common altar of humanity” In other words through this assertion of intimate communion, “holy wedlock”, we perceive that Tagore was perhaps also addressing the duality of his creative identity, by focusing firstly on the use of language for communication and secondly the use of language for creative expression ~ a ghare/baire, the known/unknown, familiar/unfamiliar binaries of the existential being and the tension of self-identity.

A split creative identity between the English Tagore and the Bengali Thakur and the reception of the respective creative texts, can be a crucial sub-text, though this aspect has not been a concern for critics and cultural commentators. As Tagore remained a prolific bi-lingual writer throughout his life, the tension between the desi Thakur and his bhasha literature and the global Tagore and his writings in English was never regarded as an act of cultural betrayal despite the fact that English in British India was a signature language of imperialism, though in this era of globalization English is now regarded as a de-territorialized global lingua franca. Significantly, Tagore continued to write in Bengali throughout his life along with writing in English. He realized that if he had to reach a larger readership, a global language like English would be a functional tool that would make him engage in a dialogue with the world.

According to many Tagore scholars, one compelling reason for this bid to introduce himself and his texts, specifically his philosophic, mystical reflections written in English, to the world, was primarily because he needed to raise funds for the maintenance of his dream project ~ Visva Bharati University, which he did tirelessly, by undertaking multiple international lecture tours. In a Sahitya Akademi curated conference on Tagore’s English writings held at Kochi, the then President of Sahitya Akademi, the celebrated author Sunil Gangopadhyay remarked unequivocally that there can be no fair competition between the Bengali writings of Tagore that comprise thirty-three volumes and the English writings of Tagore comprising four volumes that include many translations by the poet himself.

Also it would be rare for Bengalis to prefer reading Tagore in English rather than in Bengali. Sahitya Akademi’s four volumes titled The English writings of Tagore is of course a commendable initiative, as it validates the fact that Tagore could write creatively in not only Bengali but in English as well.

Volume 1 of the English Writings deals with translations or more appropriately Tagore’s transcreations from his own Bengali poems, sometimes even fusing lines and images of two or more Bengali poems in order to create one English poem. While three volumes of Tagore’s English writings have been edited by Sisir Das, the fourth volume has been edited by Nityapriya Ghosh. Interestingly, apart from the English Gitanjali, the poems of Tagore written or transcreated in English include ~ The Gardener, The Crescent Moon, Fruit-Gathering, Lover’s Gift and Crossing, The Fugitive, Stray Birds, Fireflies, The Child, one Hundred poems of Kabir among others. In fact, there are 17 poems in Crossing which seem to be poems written directly in English, as no Bengali poems could be located by Tagore scholars that even remotely resembled the content or style of these poems. In a letter from London dated 12 May 1913, to Ajit Kumar Chakravarti, Tagore had stated, “The forms and features of the original become difficult in my translations ~ the way I do them these days.

My translations are more a reflection than an exact replica of the original image.” Moreover in response to poet James Henry Cousins’s letter about his translated poems that he had sent to Cousins for his views, Tagore wrote (5 March, 1918) – “About the Englishness of my English I have to be careful as the language is not mine own, but about Ideas I think, it is best to have a definitely independent attitude of mind… (Paul vol 7 313). By using self-translation and transcreation as crafts of communication and cultural understanding, Tagore disseminated the supra-national value of poetry and showcased Bengal as an outstanding cultural space in British India.

(The writer is Professor and former Dean of Arts, Calcutta Univer)