Pakistan: Restrictions imposed on night travel on key highways in Balochistan

Amid growing unrest in Pakistan’s Balochistan, the provincial government has imposed a ban on night-time travel across several key national highways.

When it comes to recalling a movement for the dignity of the Bangla language, one often settles to remember a civil war in Pakistan that took place on 21 February 1952.

SOMEN SENGUPTA | New Delhi | May 22, 2024 7:06 am

(photo:SNS)

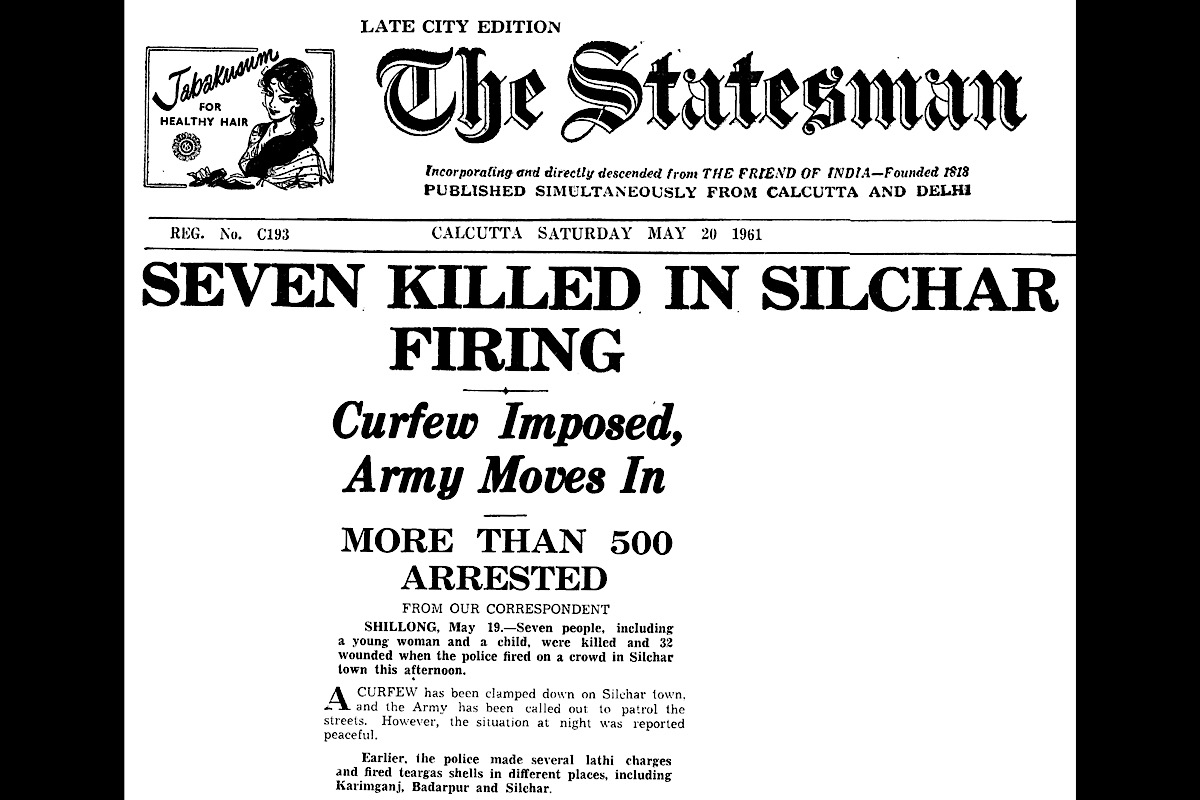

When it comes to recalling a movement for the dignity of the Bangla language, one often settles to remember a civil war in Pakistan that took place on 21 February 1952. Thanks to an extraordinarily planted narrative, Indians often forget that many more lives were sacrificed and much bigger sufferings were conceived by Bengalis of Assam in 1960–61 when they fought against Assam’s BP Chalia’s Congress Government to establish the right of Bangla as the second official language of Assam in Barak Valley, especially in Silchar, Karimganj and Hailakandi.

The linguistic demography of undivided Assam has been very complex since the British era. Though in its Brahmaputra valley, Assamese was the language of most of the people of Assam. It has a huge population living in Barak Valley, which is a Bangla-speaking zone. Sylhet, one of the richest districts of Assam, was fully Bangla-speaking.

Advertisement

The tension between Bangla-speaking and Assamese-speaking people in Assam was age-old. One of its reasons was the dominance of Bangla-speaking people in the fields of education, industry, politics, art and every single intellectual space in Assam. This was fueled in 1898 when Rabindranath Tagore, in an article published in Bharati magazine, mentioned that Assamese and Oriya were just different versions of Bangla and that they were not independent and distinguishable languages. Tagore even wrote that in Orissa and Assam, the language that must be promoted is Bangla. No doubt this created huge disgust and anger among the common Assamese mob, and soon Congress politicians used it as a political tool for their vested interests.

Advertisement

In 1946, Congress leader Lokpriya Gopinath Bordoloi of Assam expressed his desire to include Sylhet in Pakistan due to its Muslim majority but almost equal number of Hindus. A referendum was applied before the partition of India in 1947, but 1,25,155 votes were cancelled, indicating local Congress leaders mobilised voters to prevent Sylhet from coming to India. In 1950, tyranny on the Hindu community in Sylhet by the Pakistan government led to a massive influx of Bangla-speaking people migrating to Assam’s Barak Valley. In 1960, the Assam Congress proposed introducing Assamese as the only official language and medium of instruction in schools. However, protests from MLA Ranendra Mohan Das argued that Assamese was not the language spoken by most people in Assam. Despite protests, the Bangla-speaking Muslims of Assam supported the new law, though carrying out the slogans in Bangla, leading to a communal riot in Hailakandi on 19 June 1960.

On 5 February 1961, Kachar Gana Sangram Parishod (KGSP), a body dedicated to re-establishing the right to the mother tongue, was formed. To protest against the Congress government of Assam, it organised a massive walk of people, which started on 24 April and ended on 2 May. Before that, on 14 April, the people of Karimganj, Hailakandi, and Silchar observed “Sankalpa Diwas,“ which was largely attended by the Manipuris, who were equally shattered by the decision of the Assam government.

An ultimatum was given to the Assam government to announce Bangla as the second official language of the state by 13 May. A large-scale agitation in various parts of the Barak Valley was also announced on 19 May. Eventually, then Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru, who was observing the development of Assam, was scheduled to arrive in the state on 19th May itself for a three-day state visit.

The Assam government took massive steps to suppress the agitation. On 18 May, leaders of the movement, Nalinikanta Das, Rathindranath Sen and Bidhubhushan Chowdhury, were arrested. Silchar city was converted into a fortress, and an army flag march was done by the Assam Rifles, Madras Regiment, and CRPF.

A spontaneous yet peaceful strike and picketing were observed in all parts of Barak Valley on the 19th. In Silchar, a large mob blocked the railway track. The picketing at Silchar railway station was scheduled to end by 6 p.m.

By afternoon, a huge company of Assam Rifles arrived at the station and was involved in small fracas with the mob. They detained some people, and that created tension in the gathering. By 2:30 pm, anti-government slogans and din filled the air, and the army started to abuse people, and then suddenly, from nowhere, a rain of bullets were fired on the crowd with no alert. The army fired 17 rounds of bullets, and in a moment, nine people were killed. More than 100 were injured. Some were very serious. Ruthless physical abuse was done to many of the demonstrators. Young women, children, and even elders were not spared.

Those who fell to the bullets of the military of their own country only to protect the dignity of the Bangla language were Hitesh Biswas, Sukomal Purakayastha, Taruni Chandra Deb Nag, Kanailal Neogi, Sunil Sarkar, Kumud Ranjan Das, Chandi Charan Sutradhar, Sachindranath Pal and Kamal Bhattacharya. Kanailal Neyogi, who also died on the spot, was a railway parcel clerk.

One person named Birendra Sutradhar died later in the hospital, and the body of Satyendra Deb was found in a pond near the station. This took the total death toll to eleven, the highest ever in any language movement in the world. 16-year-old Kamala Bhattacharya, who was shot in the eye and died on the spot, became the first woman in the history of mankind to sacrifice her life for the sake of her language. Her younger sister, Mangala, was seriously injured and became physically disabled for the rest of her life.

The postmortem report of all these people revealed that except Sukomal Purakayastha, all were shot above their waist line, which is extremely unusual for this kind of firing.

Many who were injured later died. Names like Manik Laskar, Pradip Kumar Dutta, Krishnakanta Biswas, Anjalirani Deb, etc. were some of them.

When the Congress Government of Assam was playing with blood at Silchar, Jawaharlal Nehru was physically present in Assam. Nehru arrived in Guwahati on 19th May for a three-day state visit and asked the language movement to stop because it would not add any benefit to the Bangla language, but he remarked that Bangla was already a great language. However, even knowing the firing at Silchar in the same afternoon, he did not mention the deaths of nine people in his speech.

The Bengali press of Calcutta covered the event in vivid details and attacked the Assam government ruthlessly. It held Nehru responsible for this tragedy, pointing out his extreme inability to understand the emotions of common people related to their mother tongue. Nehru, who had been in Assam for three days, did not bother to visit Silchar then. In Bengal, the grievances of the common people against the Congress government continued. Neelam Sanjivan Reddy, then Congress President and later President of India, was attacked by one Dulal Pal with a knife at Durgapur station on 27th May. Morarji Desai, then union finance minister and later Prime Minister of India, also faced agitation at Durgapur when he arrived to participate in a Tagore centenary event.

The movement for the Bangla language in Assam got huge support from many communities other than Bengali. However, a section of Bangla-speaking Muslims in Assam and the Assam unit of the Communist Party of India did not support this movement. Fani Bora, the leader of the Assam CPI, issued a statement from Jorhat on 20th May, clearly saying that the CPI had no relation to the Bangla language movement in Assam. However, the CPI of Barak Valley and its central leadership supported the movement.

With its profound impact on national politics and the pressure mounting from the Congress party itself, the Assam government finally agreed to accept Bangla as the second official language of the Barak valley. It still enjoys this status.

The supreme sacrifice of Kamala and all those who gave their lives for the Bangla language in Assam was never celebrated with its apt importance. In Calcutta till now, there is no monument dedicated to the movement or a street or park named after the martyrs who bit the bullet for their language. Today, one event is scheduled in Calcutta’s Ram Mohan Hall by a group of people who will recall the supreme sacrifice of Silchar language warriors who gave their lives for Bengal on 19 May 1961. Perhaps, this is the only homage that they deserve from Bengal.

The writer is a freelance contributor

Advertisement

Amid growing unrest in Pakistan’s Balochistan, the provincial government has imposed a ban on night-time travel across several key national highways.

Assam Chief Minister Himanta Biswa Sarma on Sunday said that his administration is actively monitoring the train derailment involving the SMVT Bengaluru-Kamakhya AC Express in Odisha's Cuttack.

TTP announced similar ceasefires during religious festivities in the past as well.

Advertisement