20 killed, 66 injured in Israeli airstrike in Lebanon’s Beirut

At least 20 people were killed and 66 others injured in an Israeli airstrike on a residential building in the Lebanese capital Beirut, Lebanon's Ministry of Public Health reported.

All the anti-Israel protests, demonstrations, violent activities, school closures and disruptions of academic lives going on in campuses of prestigious US universities bring back memories of the infamous Naxalbari movement that I experienced during my college life in the late 1960s.

(photo:SNS)

All the anti-Israel protests, demonstrations, violent activities, school closures and disruptions of academic lives going on in campuses of prestigious US universities bring back memories of the infamous Naxalbari movement that I experienced during my college life in the late 1960s. The purpose of my essay is not to give a political analysis of causes and possible solutions to these crises, which are fundamentally different, but to offer a personal account of how the Naxalbari uprising affected my life and infer possible consequences of the present turmoil based on that experience.

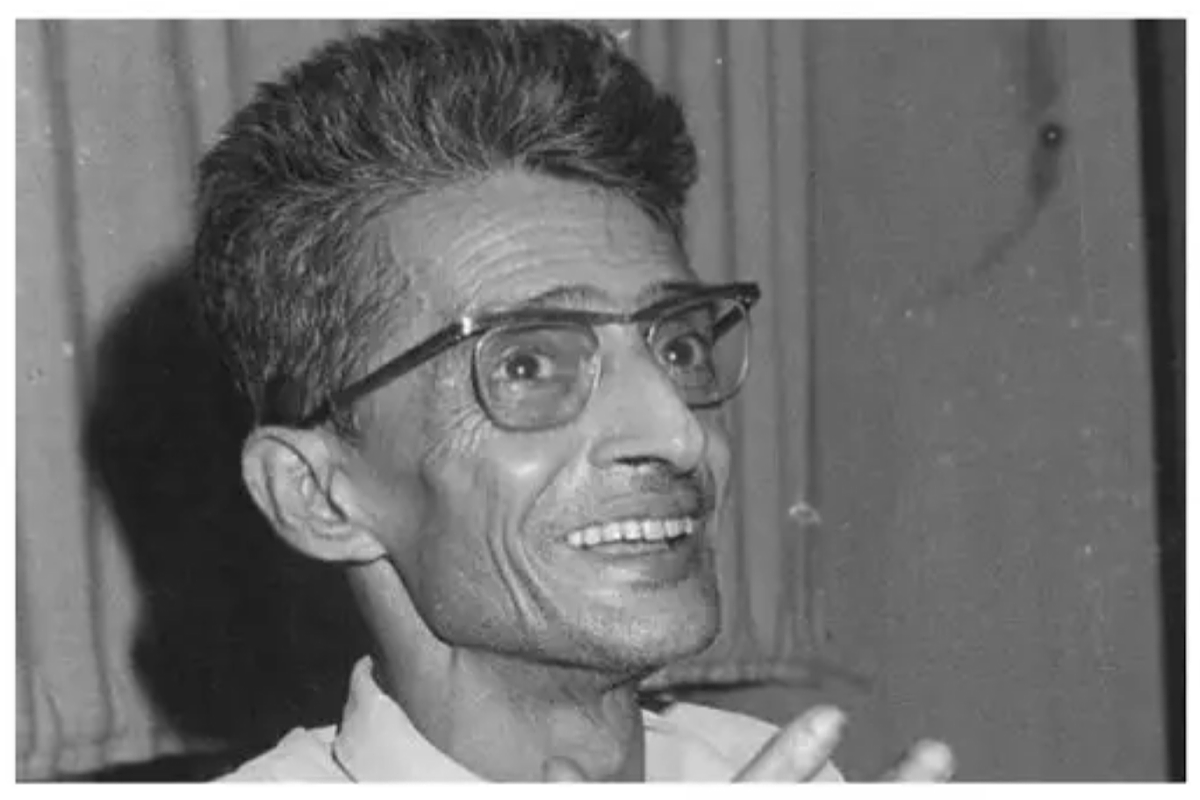

I attended the Presidency College (PC), now Presidency University, in Kolkata for my undergraduate education. At that time, it was arguably one of the best if not the best undergraduate college in India. It was ironic that, during our third year, it became the breeding ground of the Naxalite movement. The uprising started with an armed movement by rural peasants against landlords in the northern part of West Bengal. The architect of the movement behind the scenes was a group belonging to CPI-Marxist (later officially established as the CPIMarxist Leninist group) led by Charu Mazumdar (photo), Kanu Sanyal and others, who were inspired by Mao Zedong’s ideology with a grand plan of an armed revolution against the wealthy elite class.

I do not remember how it became a students’ movement except that some Naxal leaders, including Ashim Chatterjee (aka “Kaka”) were students at PC. PC was completely shut down with gates locked for almost four months with no classes, no exams, no access to lab or library and no graduation or any other ceremony. Many US campuses have recently cancelled classes for the sake of safety of students and gone to remote teaching. We did not have the luxury of a remote learning option using Zoom, but some professors secretly held classes in private residences. I do not know how beneficial the Naxal movement was and to whom, but it certainly affected me. Basically, I lost one year of the prime phase of my life, both from an academic as well as social point of view.

Advertisement

I could have graduated a year earlier, perhaps married a year earlier or not married at all and studied some other subjects for a year. In quantitative terms, I lost one year’s salary. However, the most damaging impact on me was disenchantment with not only student life but daily life in Kolkata since the movement spread beyond colleges. It seemed that there was no value in education and no hope for the future. I can honestly say that I did not come to the US for higher education; I came here to flee all the despair I felt. Some of my classmates went to universities outside Kolkata for their post-graduate schooling for the same reason.

In any event, that was the beginning of the decline in the prestige and reputation of the PC. I do not know how my life would have progressed had it not been for all these disturbances. I do know if I would have made my parents happy if I stayed in India, taken good care of them during their final years of life and helped them live a more peaceful life. At the very least, I could have been at their deathbed and performed their last rituals following the rigor described in scriptures. On the positive side, it made me much more aware of politics. I realized that what I saw starting out as a conflict of ideologies in the college union election between the Students’ Federation, an arm of the Communist party and the right leaning Presidency College Students’ Organization was really a microcosm of the greater battle between capitalism and communism, people who owned land and people who farmed land, evolution and revolution, freedom to dream and a forced ideology of equality.

I became aware of the plight, poverty, exploitation and lack of political power of the farmers. The similarity between the Naxal movement and the current anti-Israel protests by students sympathetic to Palestine and Gaza is that in both cases the events have nothing to do with students’ education and careers. If the intentions were to raise awareness of the general student body of what is going on in other parts of the world outside their comfort zone, a couple of days of demonstrations would have been sufficient. Just like the Naxal movement, there seems to be a more profound hidden agenda of a power group which is to provoke and influence young minds at best schools to make them participate in their causes, perhaps resulting in a jihad.

These students are easy targets; people are most compassionate in their youth and anxious to do something for the good of mankind. Typically, they are inexperienced in worldly affairs and ignorant of history and politics. In both cases, it was not the student bodies themselves but outsiders who created the crisis. Protests and demonstrations had always been around on college campuses. What made the Naxal movement different was the implicit threat of violence and the long duration over a widespread area covering multiple states. The present anti-Israel movements are showing some of the same signs. Some of the aftermaths are predictable.

Future students will shy away from applying to universities like Columbia, Harvard and UCLA, especially since they are not cheap. It is already happening with the admission process for the 2024-25 academic year. Some of these prestigious campuses will become breeding grounds for a radical segment whose intentions might be ideologically appealing but far from being realistic as far as practical implementation is concerned and will eventually end in a sad, unproductive way. The personal lives of many students will irrevocably change in terms of their professional aspirations, personal relationships and even patriotic feelings. Yes, these movements will make American college students, who are typically preoccupied with dating, drinking beer, sporting events and spring breaks as their extracurricular activities, much more aware of the harsh realities of people in Gaza, history of Israel, Holocaust and global politics.

Unlike the Naxal movement, the present movement may also lead to a more fundamental positive change in the higher education system in the US. I always felt that the Ivy league and similarly ranked universities exist and function because of their reputation and history. They charge enormous amounts of tuition fees and deliver little. Students at these schools excel in their studies because they are smart to begin with and the competitive spirit with fellow students who are all smart (since the schools admit only smart students) forces them to do well.

Students graduating from these schools succeed professionally because of the name recognition of their schools and subsequent acceptance/mentoring by others who also graduated from similar schools and hold important positions in various sectors. They also feel a sense of entitlement just because they have spent big money on their education: that they have the right to get better jobs, live in better neighbourhoods and have a good life. This mindset encourages geographical segregation and classification in social strata. If the big-name universities lose their glamour because of the current unrest and smart students get dispersed across other universities, eventually there could be some equity in education and subsequent collective living whether anyone learns anything about Gaza or not.

(The writer, a physicist who worked in academia and industry, is a Bengali settled in America.)

Advertisement