On World Earth Day, the United Nations led the comity of nations by addressing a triple planetary crisis to foster climate stability, and asked that we live in harmony with nature and forge a pollution-free future. But it is Mahatma Gandhi’s thoughts, shared a century ago, which remain universal lessons for all humanity. “I suggest that we are thieves in a way,” he wrote in ‘Trusteeship’. “If I take anything that I do not need for my own immediate use and keep it I thieve it from somebody else.

I venture to suggest that it is the fundamental law of Nature, without exception, that Nature produces enough for our wants from day to day, and if only everybody took enough for himself and nothing more, there would be no pauperism in this world, there would be no more dying of starvation in this world. But so long as we have got this inequality, so long we are thieving.” What he wrote in ‘Young India’, on 22 October 1925 about the ‘Seven Social Sins’ has become part of meme-lore: “Politics without Principle, Wealth Without Work, Pleasure Without Conscience, Knowledge without Character, Commerce without Morality, Science without Humanity, Worship without Sacrifice.” These sinful idiomatic phrases continue to provoke, incite, and inspire, especially ‘Science without Humanity’, in our age when climate change, carbon footprint and net-zero energy emissions are common parlance.

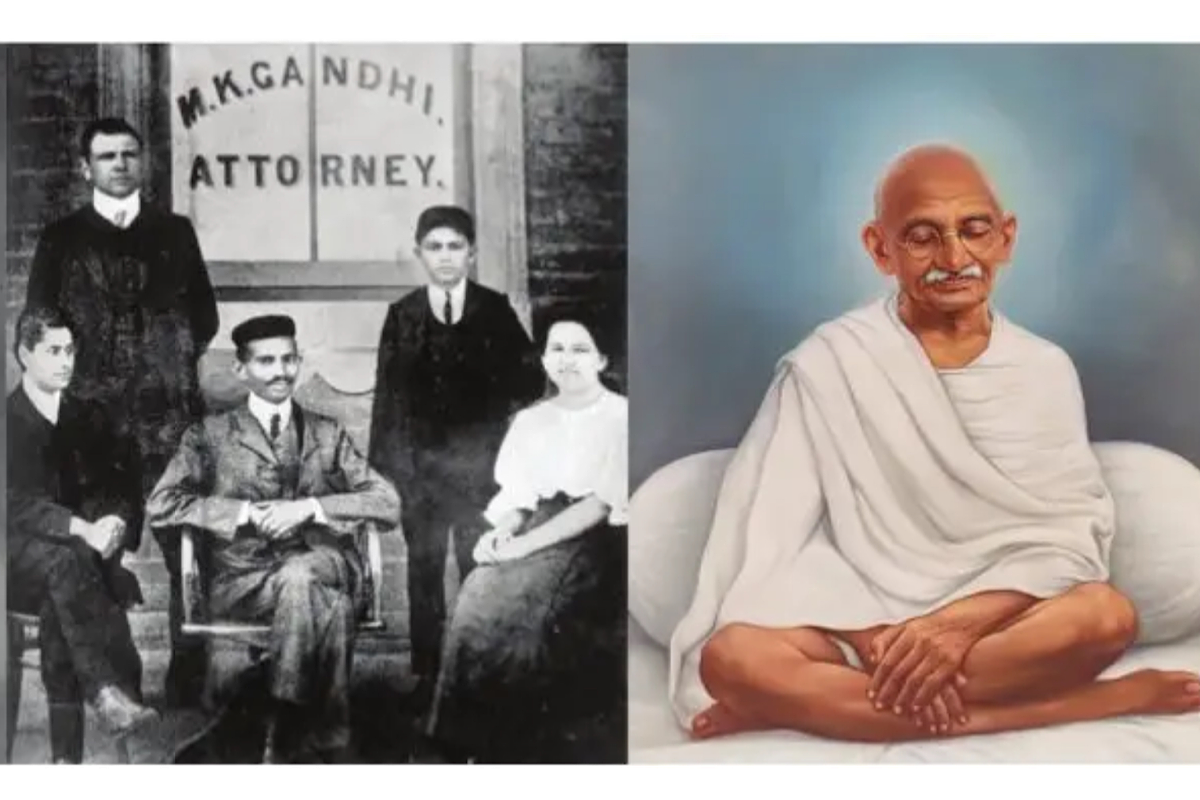

He was barely 39 years old, when Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi wrote ‘Hind Swaraj’; returning from England his mind was buzzing with issues plaguing modern civilization. It was not just the physical environment or industry, nor the condition of cities, families, and women that bothered him. Gandhiji wrote, “This civilization takes note neither of morality nor of religion. Its votaries calmly state that their business is not to teach religion. Some even consider it to be a superstitious growth. Others put on the cloak of religion, and prate about morality. But, after twenty years’ experience, I have come to the conclusion that immorality is often taught in the name of morality… Civilization seeks to increase bodily comforts, and it fails miserably even in doing so.”

Having put religion and morality at the core of civilizational growth, the young barrister explained, “This civilization is irreligion, and it has taken such a hold on the people in Europe that those who are in it appear to be half mad. They lack real physical strength or courage. They keep up their energy by intoxication. They can hardly be happy in solitude. Women, who should be the queens of households, wander in the streets or they slave away in factories. For the sake of a pittance, half a million women in England alone are labouring under trying circumstances in factories or similar institutions.

This awful fact is one of the causes of the daily growing suffragette movement. This civilization is such that one has only to be patient and it will be self-destroyed.” Turning his gaze to India, he wrote, “It is my deliberate opinion that India is being ground down, not under the English heel, but under that of modern civilization. It is groaning under the monster’s terrible weight. There is yet time to escape it, but every day makes it more and more difficult. Religion is dear to me and my first complaint is that India is becoming irreligious.

Here I am not thinking of the Hindu or the Mahomedan or the Zoroastrian religion but of that religion which underlies all religions. We are turning away from God.” His powerful words still echo after the passage of the 20th century hailed for its triumph of ‘science and technology’. ‘Hind Swaraj’ addressed the charge against Indians being lazy people, while the Europeans were industrious and enterprising. Gandhiji said, “We have accepted the charge and we therefore wish to change our condition. Hinduism, Islam, Zoroastrianism, Christianity, and all other religions teach that we should remain passive about worldly pursuits and active about godly pursuits, that we should set a limit to our worldly ambition and that our religious ambition should be illimitable. Our activity should be directed into the latter channel.”

Once again, as in ‘Trusteeship’, he wanted the readers to become religious, and unafraid to challenge Western civilization. “It is a charge against India that her people are so uncivilized, ignorant and stolid… It is a charge really against our merit,” he said. In the slim 100-page ‘Hind Swaraj’ Gandhiji provided overviews of civilizations, past and present. “That civilization which is permanent outlives it. Because the sons of India were found wanting, its civilization has been placed in jeopardy. But its strength is to be seen in its ability to survive the shock.

Moreover, the whole of India is not touched. Those alone who have been affected by Western civilization have become enslaved. We measure the universe by our own miserable foot-rule. When we are slaves, we think that the whole universe is enslaved. Because we are in an abject condition, we think that the whole of India is in that condition.” Introducing the concept of Swaraj in simple words, he wrote: “We can see that if we become free, India is free. And in this thought, you have a definition of Swaraj. It is Swaraj when we learn to rule ourselves. It is, therefore, in the palm of our hands. Do not consider this Swaraj to be like a dream. There is no idea of sitting still.

The Swaraj that I wish to picture is such that, after we have once realized it, we shall endeavour to the end of our lifetime to persuade others to do likewise. But such Swaraj has to be experienced, by each one for himself. One drowning man will never save another. Slaves ourselves, it would be a mere pretension to think of freeing others.” It is only towards the end of ‘Hind Swaraj’ that Gandhiji focused on machinery and industrialization as witnessed during his stay in England. “Machinery has begun to desolate Europe. Ruination is now knocking at the English gates. Machinery is the chief symbol of modern civilization; it represents a great sin. The workers in the mills of Bombay have become slaves. The condition of the women working in the mills is shocking.

When there were no mills, these women were not starving. If the machinery craze grows in our country, it will become an unhappy land. It may be considered a heresy, but I am bound to say that it were better for us to send money to Manchester and to use flimsy Manchester cloth than to multiply mills in India. By using Manchester cloth we only waste our money; but by reproducing Manchester in India, we shall keep our money at the price of our blood, because our very moral being will be sapped, and I call in support of my statement the very millhands as witnesses. And those who have amassed wealth out of factories are not likely to be better than other rich men.” The anti-machinery arguments flowed: “Machinery is like a snake-hole which may contain from one to a hundred snakes.

Where there is machinery there are large cities; and where there are large cities, there are tramcars and railways; and there only does one see electric light. English villages do not boast of any of these things. Honest physicians will tell you that where means of artificial locomotion have increased, the health of the people has suffered…I cannot recall a single good point in connection with machinery. Books can be written to demonstrate its evils.” These contrarian views of Gandhiji, in an age when capitalism was thriving, remain relevant when he said: “Impoverished India can become free, but it will be hard for any India made rich through immorality to regain its freedom.

I fear we shall have to admit that moneyed men support British rule; their interest is bound up with its stability. Money renders a man helpless. The other thing which is equally harmful is sexual vice. Both are poison. A snakebite is a lesser poison than these two, because the former merely destroys the body but the latter destroys body, mind and soul.” Swaraj, Swadeshi and Home Rule were inter-connected and intertwined when Gandhiji questioned: “What need, then, to speak of matches, pins, and glassware? My answer can be only one. What did India do before these articles were introduced? Precisely the same should be done today.

As long as we cannot make pins without machinery, so long will we do without them. The tinsel splendor of glassware we will have nothing to do with, and we will make wicks, as of old, with homegrown cotton and use handmade earthen saucers for lamps. So doing, we shall save our eyes and money and support Swadeshi and so shall we attain Home Rule.” About civilizations, nature, machinery, and lives of people, Gandhiji warned, “It is necessary to realize that machinery is bad. We shall then be able gradually to do away with it. Nature has not provided any way whereby we may reach a desired goal all of a sudden. If, instead of welcoming machinery as a boon, we should look upon it as an evil, it would ultimately go.”

(The writer is an authorresearcher on history, and a former deputy curator of Pradhanmantri Sangrahalaya)