Unfinished Agenda

Mahatma Gandhi, the greatest man of the twentieth century, often talked about poverty. For the prophet of non-violence, poverty was the worst form of violence.

Long before the Salt Satyagraha was launched by Mahatma Gandhi from Sabarmati Ashram in Ahmedabad on 12 March 1930, there were popular uprisings, hunger-strikes in jails, workers’ strikes and public processions denouncing the ruthless colonial rule subjugating the country.

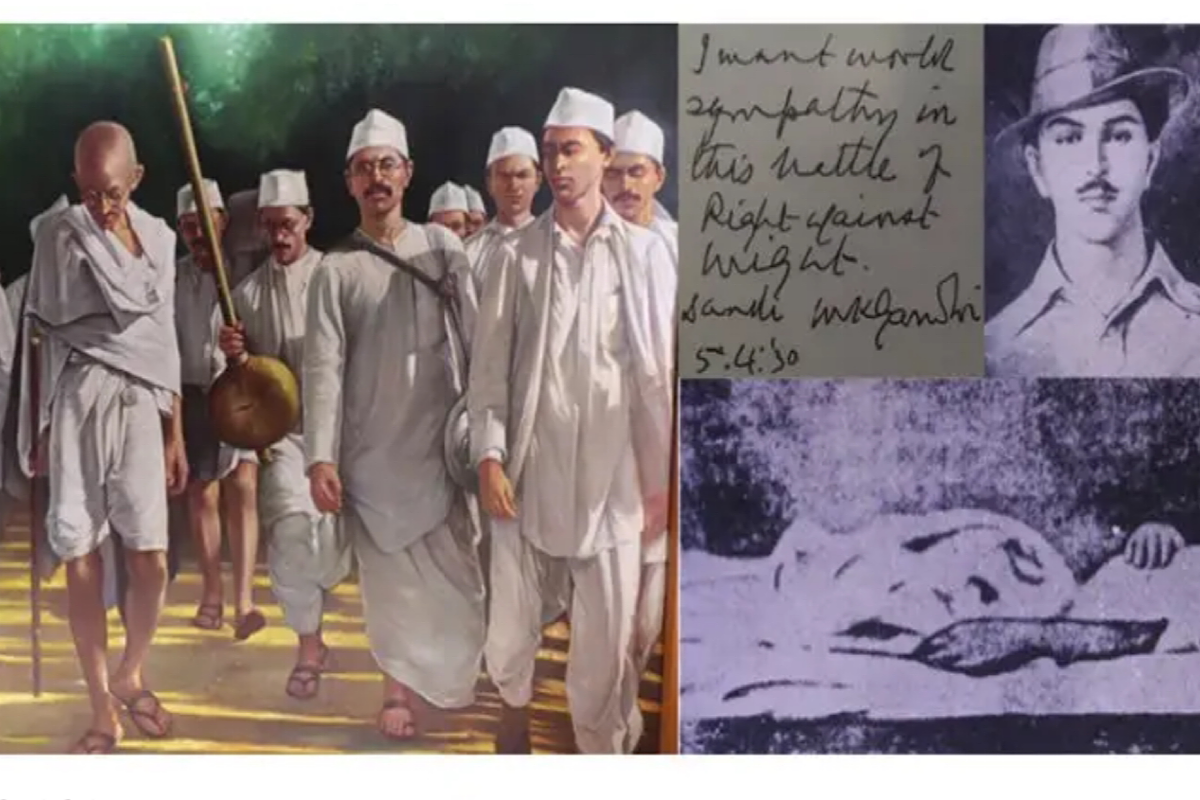

(Photos: Bhagat Singh, Batukeswar Dutta, Jatin Das on death-bed; painting at Sabarmati Ashram depicting Gandhiji leading the march)

Long before the Salt Satyagraha was launched by Mahatma Gandhi from Sabarmati Ashram in Ahmedabad on 12 March 1930, there were popular uprisings, hunger-strikes in jails, workers’ strikes and public processions denouncing the ruthless colonial rule subjugating the country. British authorities were alarmed and determined to put an end to these demonstrations through beatings, police firings and indescribable tortures. Gandhiji’s Dandi March, as the Salt Satyagraha is referred to, was defying British laws prohibiting common manufacture of salts in India: it sparked the imagination of the people, near and far through March to May 1930.

It was an intensely active non-violent revolution which brought to the fore what Raja Rammohun Roy had enumerated in 1831, almost a hundred years earlier. Standing before the ad hoc Committee of the British parliament in London, Rammohun Roy left no one in any illusion about the plunder and self-serving nature of the English East India Company. The Company had run a deplorable drainage of the Indian economy, sacrificing the interests of millions of Indians to profit for an English elite. This was several decades before Dadabhai Naoroji and RC Dutt could spell out ‘the drain of wealth’ theory with more hardhitting facts. He denounced abuses of the Company concerning salt trade in India; pointing out that in Bengal alone, 125,000 manufacturers of salt (molunghi) had become victims of this severe monopoly of the English.

The patriotic fervor seen during the Dandi March was building up with the Meerut Conspiracy case of 20 March 1929, and the publicity it received in India and overseas. The British carried out widespread simultaneous searches throughout India and arrested 31 Communist and trade union leaders. They wanted to prove in court that “Communists were anti-religion, antinational and anti-everything that is civilised in society”. Harold Laski, the British political scientist, likened the Meerut trial “to the class of cases of which the Mooney trial and the Sacco-Vangetti trial in America, Dreyfus trial in France, the Reichstag fire trial in Germany, are supreme instances.”

Advertisement

With the nationalist press in India, and Communist press abroad, giving full publicity, the Meerut Conspiracy case became widely known, inspiring a new generation of Indian revolutionaries. Sure enough, the second Meerut Conspiracy shook the colonial government. On 8 April 1929, in the Central Legislature at Delhi, the Public Safety Bill and the Trade Dispute Bill were certified as lawful acts by the Viceroy. Immediately, in protest of such anti-working class activity of the Government, the revolutionary Bhagat Singh and Batukeswar Dutta threw two bombs in the Legislature hall.

They did not try to escape, instead shouted: “Long Live Revolution”, ”Down with imperialism”, “Workers of the World Unite” and distributed handbills, published in the name of Hindusthan Socialist Republican Army (HSRA), headlined, “In order that the deaf might listen, the noise must be powerful.” When Jatin Das, another HSRA revolutionary, died in Lahore Jail after a 63-day hunger strike on 13 September 1929, patriotism and anti-British emotions reached new pitch with leaders like Subhas Chandra Bose and Durgavati Devi joining a massive funeral procession in Calcutta four days later, an unprecedented outpouring of compassion and empathy for the sacrifices of HSRA revolutionaries.

From Bengal came another show of anti-British power in the jute mills of Chengail and Bauria where workers began a long strike, refusing to bow before police attacks and retrenchment. By July-August 1929, the first general strike of jute works assumed historic proportions: a record 192,000 jute workers of Bengal were united through this struggle. Leaders like Abdul Momin, Abdur Rezzak Khan, Kali Sen and Dr Bhupendranath Dutta were engaged in these struggles, a recurring nightmare for the Government. With these fires of freedom burning in 1929, the Congress at its Lahore session in December, resolved for complete Independence or Poorna Swaraj.

On 26 January 1930, Independence Day was observed all over the country. The pledge was taken for not resting till complete Independence was gained when the national flag was unfurled. It was in this political context that Mahatma Gandhi on 11 March 1930 announced the Dandi March, at the evening prayer held on Sabarmati sands with a 10,000-strong crowd listening to his memorable dramatic speech. He said, “In all probability this will be my last speech to you. Even if the Government allows me to march tomorrow morning, this will be my last speech on the sacred banks of the Sabarmati. Possibly these may be the last words of my life here. I have already told you yesterday what I had to say. Today I shall confine myself to what you should do after my companions and I are arrested.

The programme of the march to Jalalpur must be fulfilled as originally settled. The enlistment of the volunteers for this purpose should be confined to Gujarat only. From what I have seen and heard during the last fortnight, I am inclined to believe that the stream of civil resisters will flow unbroken.” His emphasis on non-violence was constant: “Let there be not a semblance of breach of peace even after all of us have been arrested. We have resolved to utilize all our resources in the pursuit of an exclusively non-violent struggle. Let no one commit a wrong in anger.

This is my hope and prayer. I wish these words of mine reached every nook and corner of the land. My task shall be done if I perish and so do my comrades. It will then be for the Working Committee of the Congress to show you the way and it will be up to you to follow its lead. So long as I have reached Jalalpur, let nothing be done in contravention to the authority vested in me by the Congress.

But once I am arrested, the whole responsibility shifts to the Congress. No one who believes in non-violence, as a creed, need therefore sit still. My compact with the Congress ends as soon as I am arrested. In that case volunteers, wherever possible, civil disobedience of salt should be started. These laws can be violated in three ways. It is an offence to manufacture salt wherever there are facilities for doing so. The possession and sale of contraband salt, which includes natural salt or salt earth, is also an offence.

The purchasers of such salt will be equally guilty. To carry away the natural salt deposits on the seashore is likewise violation of law. So is the hawking of such salt. In short, you may choose any one or all of these devices to break the salt monopoly.” “I stress only one condition, namely, let our pledge of truth and nonviolence as the only means for the attainment of Swaraj be faithfully kept,” he explained, “For the rest, every one has a free hand.

But that does not give a license to all and sundry to carry on their own responsibility. Wherever there are local leaders, their orders should be obeyed by the people. Where there are no leaders and only a handful of men have faith in the programme, they may do what they can, if they have enough self-confidence…Our ranks will swell and our hearts strengthen, as the number of our arrests by the Government increases.” Gandhiji’s focus was not just on salt alone, his words, “the Liquor and foreign cloth shops can be picketed. We can refuse to pay taxes if we have the requisite strength. Lawyers can give up practice. Public can boycott law courts; Government servants can resign their posts. People quake with fear of losing employment.

Such men are unfit for Swaraj… If, therefore, we are sensible enough, let us bid good-bye to Government employment, no matter if it is the post of a judge or a peon. Let all who are co-operating with the Government in one way or another, be it by paying taxes, keeping titles, or sending children to official schools, etc. withdraw their co-operation in all or as many ways as possible. Then there are women who can stand shoulder to shoulder with men in this struggle.” “You may take it as my will,” he said, adding “It was the message that I desired to impart to you before starting on the march or for the jail.

I wish that there should be no suspension or abandonment of the war that commences tomorrow morning or earlier, if I am arrested before that time. A Satyagrahi, whether free or incarcerated, is ever victorious. He is vanquished only, when he forsakes truth and nonviolence and turns a deaf ear to the inner voice. God bless you all and keep off all obstacles from the path in the struggle that begins tomorrow.”

(The writer is an authorresearcher on history and heritage issues, and a former deputy curator of Pradhanmantri Sangrahalaya)

Advertisement