A miscellany of book reviews

From books on US policies, the Russia-Ukraine War to notorious terrorist bodies operating in India and the trans-national arena, here' a miscellany of book reviews.

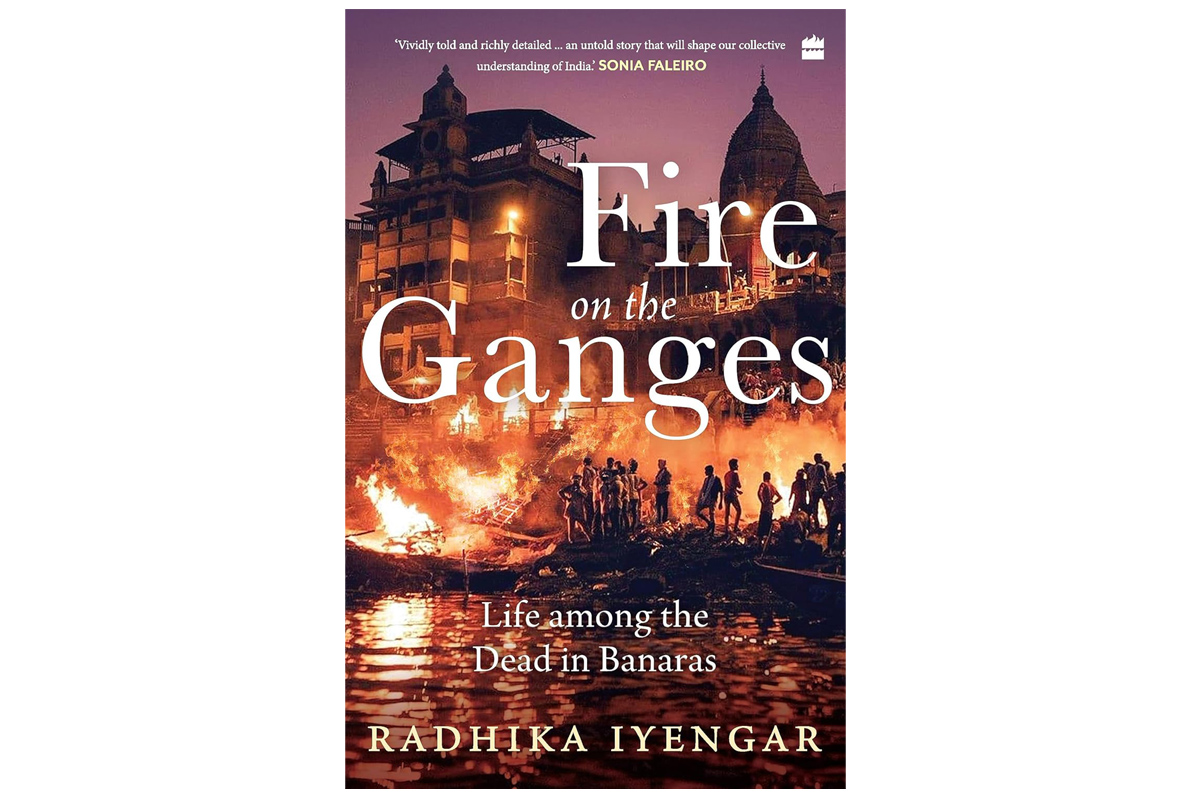

Fire on the Ganges is an insightful yet compassionate book that hits hard with its bare facts by examination of the systemic gaps within a highly stratified society that systematically marginalises the specific community of the Doms, depriving them of even the basic remnants of humanity.

In the sacred city of Varanasi, where the Ganges meanders through ancient ghats and ancient temples, a profound ritual unfolds daily along its riverbanks—a ritual that has both captivated and confounded the imaginations of observers for centuries.

This mystifying practice of the burning of corpses in Hinduism, is a sacred act believed to liberate the soul, a step towards attaining salvation.

Journalist Radhika Iyengar’s debut book, Fire on the Ganges: Life among the Dead in Banaras, is based on the marginalised group of the Doms— the individuals responsible for cremating corpses in Banaras, and whose livelihood is intimately tied to the morbidity that surrounds them. Mandated with the solemn duty of performing Hindu cremation rituals, the Doms, branded as ‘untouchables’, find themselves relegated to the lowest echelon of the caste hierarchy. The right to aspire is a privilege denied to these members of the Dalit sub-caste. The scant semblance of life they experience is intricately intertwined with the pyres ablaze on the ghats of the sacred city, and their societal value is inexorably linked to the departed—quite literally deriving their social currency from the deceased.

Advertisement

The narrative commences with the introduction of Dolly Chaudhary, a young widow whose husband, Sekond Lal Chaudhary, was a practitioner of the solemn task of cremating the deceased. On the night of her husband’s cremation, Dolly is conspicuously absent, denied the opportunity to witness the final rites of her own spouse. The author sheds light on the prevailing belief within the community, asserting that women are deemed too fragile in spirit to endure the emotional rigours associated with the solemnity of cremation ceremonies. “The community believed that women are too weak-hearted to be present at cremations”, Iyengar writes. This cultural perception, deeply embedded in tradition, marks the inception of the book, underscoring the gendered norms and societal expectations that shape the experiences of individuals within the community of corpse-burners.

The sketch unfolds, delving deeper into the melancholic tale of Dolly, a widow barely in her thirties burdened with the responsibility of providing for her five children. Within the confines of the Dom community, the lives of its women, regardless of age or marital status, unfold against a backdrop of dimly lit homes where the routine revolves around the mundane tasks of cooking and cleaning utensils. The societal constraints are palpable; a married Dom woman can only venture beyond the community’s limits with a male companion, and unmarried women find themselves similarly tethered, unable to wander alone on a “whim”. The pervasive gaze of surveillance casts a shadow over every movement, enforcing a disheartening reality where women are perpetually under scrutiny.

In this oppressive environment, where a woman’s worth is intricately tied to the presence of her husband, Dolly’s story emerges as a poignant departure from the norm. Despite the patriarchal confines that seek to confine Dom women within domestic spheres, Dolly defies these constraints by courageously establishing her own shop. Her resilience becomes a flicker of light in the dimness, a testament to the strength required to carve out an identity beyond societal expectations and challenge the pervasive belief that a woman without her husband holds no intrinsic value.

Through her insightful interviews, author Radhika Iyengar skillfully unveils the nuanced emotions of the women featured in the narrative, allowing them to transcend the confines of stereotypical roles. Within the pages of the book, these women emerge as multifaceted and rebellious individuals—confident matriarchs, defiant daughters-in-law and ambitious young girls—breaking free from the rigid societal expectations that seek to define them.

One notable figure is Komal, a young Brahmin girl residing in a Yadav colony, entangled in a forbidden romance with Lakshya, a Dom boy. In a narrative that echoes the pervasive societal norms in India, Komal finds herself burdened with the “honour” of her community once her clandestine relationship is exposed. The aftermath is a haunting tale of harassment and torment. However, Komal summons the strength within herself to take a daring step, one that holds the promise of a potentially better life. Another of these women with indomitable spirits is Kamala Devi. Her matriarchal strength is evident as she manages to sustain her home and provide for her nine children despite enduring an abusive marriage.

The book transcends the ethereal and legendary tales of life and rebirth, stories that have come to dominate the popular narrative surrounding the city of Banaras. Iyengar, instead, delves into the sombre reality of the business of death, shining a gloomy light on the narratives of labour that metaphorically and literally stoke the critical flames defining the city.

The poignant accounts unveil haunting images—bones succumbing to the relentless grasp of flames, shrouds collected by children and exchanged for meagre sums, and the painstaking sifting through ashes and bones to salvage bits of metal, bartered for a modest reprieve in the form of a snack.

In the chronicle’s depths, a five-year-old confronts death for the first time, encountering the lifeless form of a man bearing the scars of violence with a sewn-up eye. A cremator’s revelation to Iyengar unveils the chilling reality that bodies, subjected to prolonged suffering from illness, injected with an array of fluids and medicines during their weeks in hospitals, demand a prolonged ritual—six to seven hours, compared to the customary three—for the fire to fully consume them. These grim revelations paint a haunting portrait of the profound struggles and realities faced by those ensnared in the relentless cycle of life, death, and the unforgiving flames that bridge the two.

Within the chapter titled Fleeing the Crabs, Iyengar meticulously captures a significant tale of mobility within the Dom community—a narrative centred around the life of Bhola Chaudhary, a 24-year-old who stands as a trailblazer by becoming the first from the Dom community to venture beyond the confines of Banaras and enrol in a private university. In this compelling account, readers are granted an intimate look into Bhola’s journey of assimilation into an environment far removed from the familiar streets of his hometown.

Iyengar unravels the complexities of Bhola’s experience as he navigates the challenges of fitting in among his more affluent peers, highlighting the palpable unease that accompanies interactions with those who hail from different socio-economic backgrounds. The tale delicately unfolds the layers of Bhola’s internal struggle, emphasising his hesitancy in divulging his origins to others. In a poignant moment, Bhola confesses, “I don’t let anyone know what or who I am,” underscoring the weight of societal perceptions and the enduring struggle to define one’s identity beyond the constraints of a predetermined narrative.

Fire on the Ganges is an insightful yet compassionate book that hits hard with its bare facts by examination of the systemic gaps within a highly stratified society that systematically marginalises the specific community of the Doms, depriving them of even the basic remnants of humanity.

Iyengar, in her work, deliberately emphasises the resilience and fortitude of the individuals she portrays, steering away from casting them solely as victims. Despite projecting an exterior of unwavering strength and an unsettling serenity, the women in the book harbour within them the latent embers of fury, feelings of betrayal, the weight of injustice and deep-seated resentment.

The book not only sheds light on the inherent complexities of the life of a Dom, but also serves as a testament to the indomitable spirit that propels these people toward paths of self-determination and the pursuit of a life that transcends the limitations set by society. The Doms, simmering with these unspoken emotions, embody a paradoxical blend of strength and vulnerability, challenging societal norms while maintaining a facade of resilience. Similar to their occupation, the flames within their souls persist, relentlessly striving to liberate themselves from the constraints of societal expectations. The key distinction lies in the perpetual nature of the fire within their spirits, never succumbing to extinguishment.

The reviewer is a journalist on the staff of The Statesman.

Advertisement