Parting shot

The outgoing Biden Administration’s authorisation for Ukraine to carry out long-range missile strikes against Russian targets using US weaponry signals a significant escalation in the on-going conflict.

Is it inevitable that Donald Trump will be the Republican nominee for US president for a third race in a row? To answer this question, we must understand the political dynamics in the United States at a deeper level than the headlines. The Republican Party is in the midst of a nearly unprecedented drama.

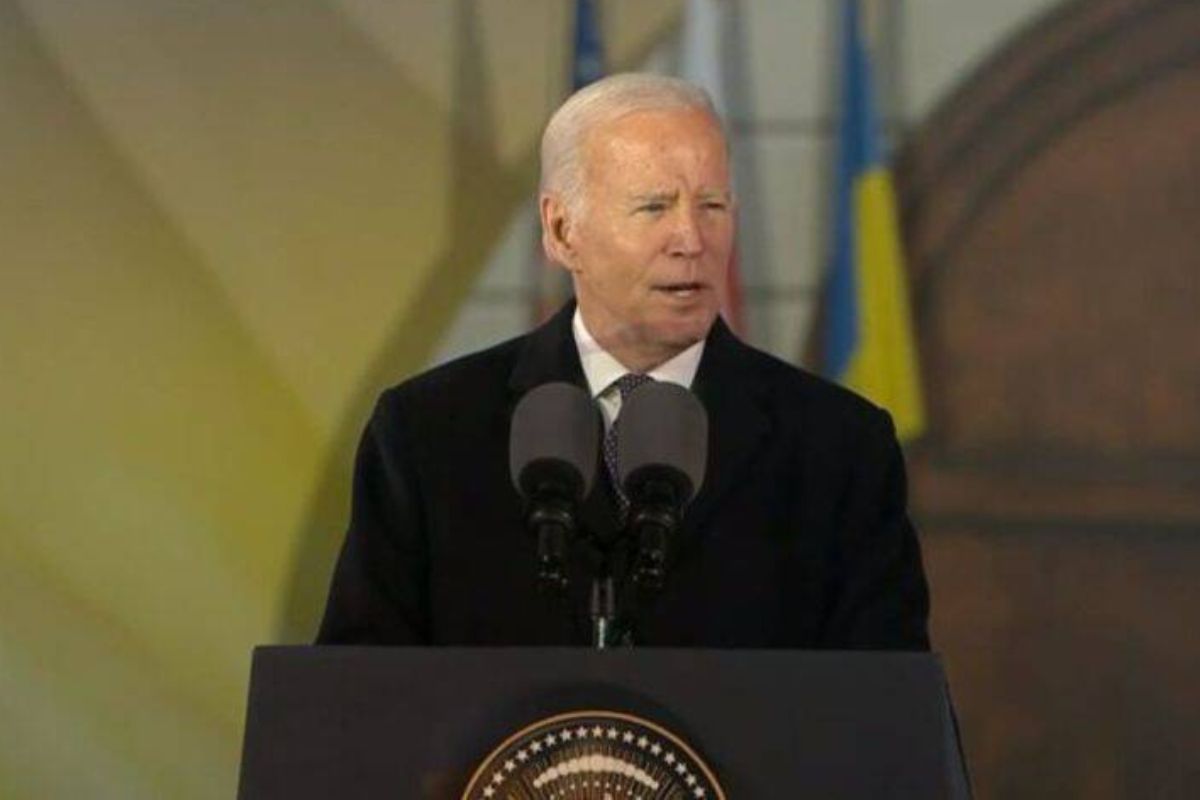

US President Joe Biden (Screengrab from The White House YouTube)

Is it inevitable that Donald Trump will be the Republican nominee for US president for a third race in a row? To answer this question, we must understand the political dynamics in the United States at a deeper level than the headlines. The Republican Party is in the midst of a nearly unprecedented drama. Not since Herbert Hoover in 1940 has a former US president campaigned for another term in the Oval Office.

And this time, Trump is also managing a slew of criminal and civil charges – yet remains the frontrunner for the nomination. It is political gospel in the US that voters rarely admit they made a mistake in the voting booth and will continue to support parties and candidates they voted for in the past.

This means that, for all of his personal sins, rude insults, felony indictments and electoral defeats, Trump remains relatively popular with Republican voters, the majority of whom want to see him return to his old job running the White House. Indeed, polling indicates the indictments actually strengthened the former president’s position among Republican voters.

Advertisement

Because of his popularity within the party, Trump has been able to skip Republican candidate debates, define his own path to the state nomination caucuses and primaries, and keep well ahead of his rivals in the polls. He uses his criminal indictments as evidence the establishment is out to get him, further cementing the “outsider” status his voters love.

During the first Republican debate he sat down with former Fox News host Tucker Carlson for a lengthy clickbait interview. During the second debate, Trump spoke with striking auto workers in the swing state of Michigan. No other Republican candidate is strong enough even to attempt this – at least, not yet. For Trump’s challengers, who lack this flexibility, a great winnowing is now underway.

The question today is not whether one of them can move past Trump in the polls, but rather which one will emerge as the main alternative. The previous two debates – and there will be at least one more – should be seen in this context. Two candidates appear to be emerging from this winnowing: Governor Ron DeSantis of Florida and Nikki Haley, the former governor of South Carolina and the Trump administration’s ambassador to the United Nations. Haley and DeSantis are pursuing different constituencies within the Republican Party, particularly in their approaches to foreign policy questions.

Haley has effectively attacked the isolationist America-first policies of the previous Trump administration and vigorously defended US military aid to Ukraine. Her open appeal to the internationalist wing of the party will win her no friends among hardcore Trumpers. DeSantis is playing a more nuanced game – attempting to appeal to isolationist Republicans by saying things like “Ukraine is a territorial dispute” and “we are not going to have a blank check” and “we will make the Europeans do what they need to do”.

These statements strongly communicate scepticism of a vigorous US role in Ukraine. The bet here, however, is that this is a feint. DeSantis is following in the footsteps of Ronald Reagan, who as a candidate in both 1976 and 1980 routinely condemned prior US presidents’ Panama Canal treaties as a giveaway to foreigners. However, once he was in office, he did not abrogate them.

DeSantis may sound like a nationalist, but there is nothing in his various statements on Ukraine that would necessitate withdrawal of US support for the fight against the Russian invasion. If he wins the presidency, look for a substantive pivot towards a more internationalist policy agenda. The Haley-DeSantis battle is about more than foreign policy, of course.

Haley is making an appeal to Republican women with a relatively moderate position on abortion – opposing a federal limit on the procedure. DeSantis is looking to draw Trump supporters by bragging about his various efforts to fight socially liberal social policies and their corporate advocates.

In the two-person battle to be the Trump alternative, Haley may have a structural advantage over DeSantis in that she doesn’t have to pull as many of her supporters away from Trump. As the other candidates fall away, their supporters will likely side with Haley.

Vivek Ramaswamy’s supporters may end up with DeSantis, although the animosity between Trump and the Florida governor may limit that. Trump’s great political vulnerability is that since 2016, he has been an electoral loser. He lost the majority in both houses of Congress in 2018, he lost re-election to Joe Biden in 2020, and he cost the Republicans a shot at winning the Senate in 2022 by personally supporting losing candidates in Georgia and Pennsylvania.

Whether Haley or DeSantis wins the contest to be the alternative to the former president – and look for that winner to emerge just before or during the Iowa Caucus in January 2024 – they will have to challenge Trump at his weakest spot: his demonstrated inability to defeat Biden in an election.

Trump has spent the past three years denying he lost the 2020 election. As a world-class political athlete, Trump knows his Achilles heel is his loss to Biden. For Trump to be a viable candidate in 2024, he must sow doubt about that loss. He has done so effectively, at least within the primary voter base, with a majority of Republican voters still believing Biden didn’t win legitimately.

For Haley or DeSantis to prevail and become the Republican presidential nominee, they will have to dismantle that Big Lie and force voters to confront the likelihood that Trump will lose and Biden will win a second term. If and when that battle begins, most likely between Trump and Haley, we will see the real future of the Republican Party and who will oppose Biden in the 2024 general election.

(The writer is Non-resident fellow, United States Studies Centre, University of Sydney. This article was published on www.theconversation.com)

Advertisement