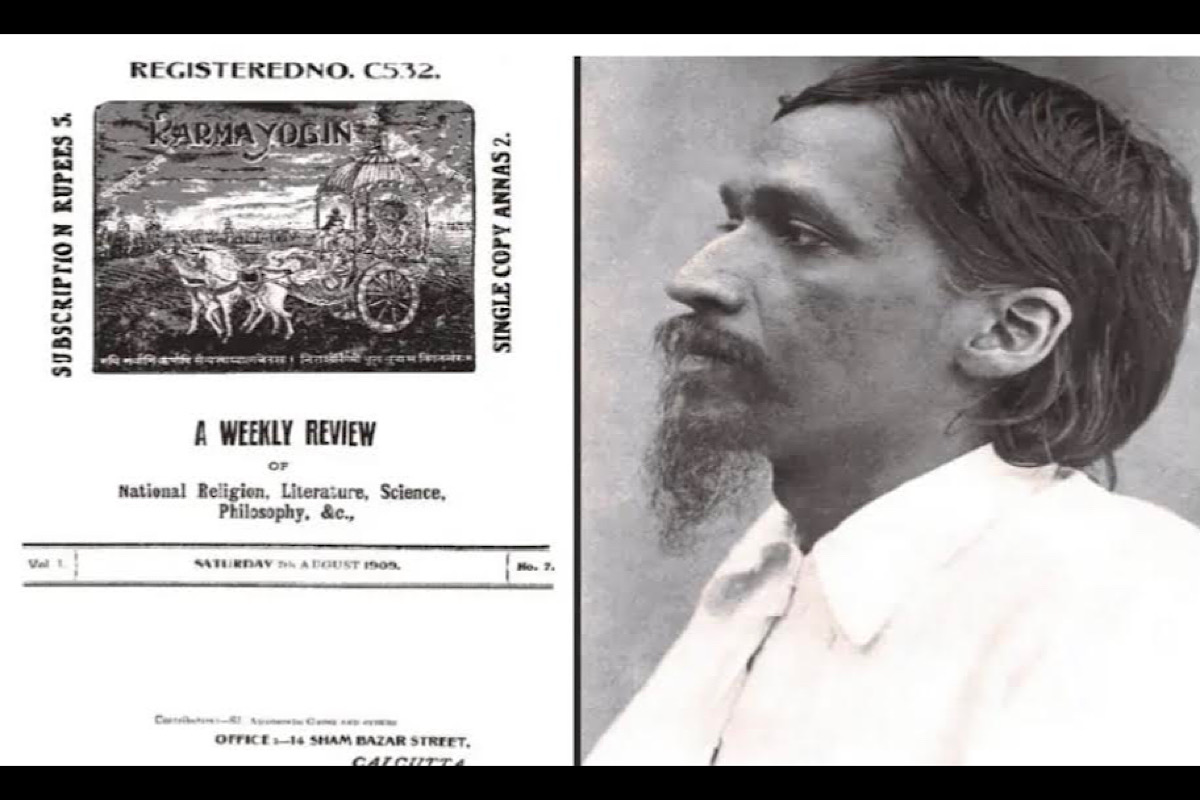

On his release from jail after the Alipore Bomb trial concluded in May 1909, Aurobindo Ghose launched ‘Karmayogin’, a weekly journal, on 19 June 1909. Its objective was to focus readers’ attention on issues of national religion, literature, science, and philosophy.

Till he left Calcutta in February 1910, Aurobindo Ghose was writing most of the journal contents himself; these were in the form of essays on subjects of yoga, education, art and literature as well as translations and poetry, proof of his intellectual depth and urge to share knowledge to inspire his countrymen. When later in life a disciple of Sri Aurobindo reviewed his earlier writings, especially in ‘Karmayogin’ (In Volume 8 Collected Works of Sri Aurobindo), his response was revealing.

Advertisement

He said, “I don’t think it can be published in its present form as it prolongs the political Aurobindo of that time into the Sri Aurobindo of the present time. You even assert that I have ‘thoroughly’ revised the book and these articles are an index of my latest views on the burning problems of the day and there has been no change in my views in 27 years (which would surely be proof [of ] a rather unprogressive mind).” He questioned: “How do you get all that? My spiritual consciousness and knowledge at that time was as nothing to what it is now ~ how would the change leave my view of politics and life unmodified altogether?” While the spiritual journey of Sri Aurobindo continued, the Uttarpara speech of 1909 from the pages of ‘Karmayogin’ unveils his dialogue with divinity. He said, “…always I listened to the voice within: ‘I am guiding, therefore fear not. Turn to your own work for which I have brought you to jail and when you come out, remember never to fear, never to hesitate.

Remember that it is I who am doing this, not you nor any other. Therefore whatever clouds may come, whatever dangers and sufferings, whatever difficulties, whatever impossibilities, there is nothing impossible, nothing difficult. I am in the nation and its uprising and I am Vasudeva, I am Narayana, and what I will, shall be, not what others will. What I choose to bring about, no human power can stay’.” There is pain, a sense of embarrassment he shared with the audience in the Uttarpara public library. “You have spoken much today of my self-sacrifice and devotion to my country.

I have heard that kind of speech ever since I came out of jail, but I hear it with embarrassment, with something of pain. For I know my weakness, I am a prey to my own faults and backslidings. I was not blind to them before and when they all rose up against me in seclusion, I felt them utterly. I knew then that I the man was a mass of weakness, a faulty and imperfect instrument, strong only when a higher strength entered into me.” These were invaluable lessons in understanding human existence: problems arising from seclusion; frailties and weaknesses which become apparent, and imperfection which seeks remedies not easily found. In jail, Aurobindo Ghose had apprehensions on preparing the legal defense.

Then he came to know Srijut Chittaranjan Das had assumed charge as defence counsel. He said, “When I saw him (Chittaranjan Das), I was satisfied, but I still thought it necessary to write instructions. Then all that was put from me and I had the message from within, ‘This is the man who will save you from the snares put around your feet. Put aside those papers. It is not you who will instruct him. I will instruct him’. From that time I did not of myself speak a word to my Counsel about the case or give a single instruction and if ever I was asked a question, I always found that my answer did not help the case.” Aurobindo Ghosh shared these divine revelations during the speech; it was a confessional act, demonstrating his sincerity to uplift the audience. He narrated the coming of the second message. “It said, ‘Something has been shown to you in this year of seclusion, something about which you had your doubts and it is the truth of the Hindu religion. It is this religion that I am raising up before the world, it is this that I have perfected and developed through the rishis, saints, and avatars, and now it is going forth to do my work among the nations. I am raising up this nation to send forth my word.

This is the Sanatana Dharma, this is the eternal religion which you did not really know before, but which I have now revealed to you. The agnostic and the sceptic in you have been answered, for I have given you proofs within and without you, physical and subjective, which have satisfied you’.” Challenges were set out for Aurobindo Ghose by divinity when Sanatana Dharma and its role was outlined for the future of India.

He recounted the divine dialogue, “‘When you go forth, speak to your nation always this word that it is for the Sanatana Dharma that they arise, it is for the world and not for themselves that they arise. I am giving them freedom for the service of the world. When therefore it is said that India shall rise, it is the Sanatana Dharma that shall rise. When it is said that India shall be great, it is the Sanatana Dharma that shall be great. When it is said that India shall expand and extend herself, it is the Sanatana Dharma that shall expand and extend itself over the world. It is for the dharma and by the dharma that India exists’.” The dialogue continued, resonating with the exchange of Arjuna and Lord Krishna in the Bhagavad Gita.

Aurobindo detailed the revelations in these words: “To magnify the religion means to magnify the country. I have shown you that I am everywhere and in all men and in all things, that I am in this movement and I am not only working in those who are striving for the country but I am working also in those who oppose them and stand in their path. I am working in everybody and whatever men may think or do they can do nothing but help on my purpose. They also are doing my work; they are not my enemies but my instruments. In all your actions you are moving forward without knowing which way you move. You mean to do one thing and you do another.

You aim at a result and your efforts subserve one that is different or contrary. It is Shakti that has gone forth and entered into the people. Since long ago I have been preparing this uprising and now the time has come and it is I who will lead it to its fulfilment.” To the audience in Uttarpara, Aurobindo questioned, “This then is what I have to say to you… But what is the Hindu religion? What is this religion which we call Sanatana, eternal?

It is the Hindu religion only because the Hindu nation has kept it, because in this peninsula it grew up in the seclusion of the sea and the Himalayas, because in this sacred and ancient land it was given as a charge to the Aryan race to preserve through the ages. But it is not circumscribed by the confines of a single country, it does not belong peculiarly and forever to a bounded part of the world.” “That which we call the Hindu religion is really the eternal religion, because it is the universal religion which embraces all others. If a religion is not universal, it cannot be eternal. A narrow religion, a sectarian religion, an exclusive religion can live only for a limited time and a limited purpose.

This is the one religion that can triumph over materialism by including and anticipating the discoveries of science and the speculations of philosophy. It is the one religion which impresses on mankind the closeness of God to us and embraces in its compass all the possible means by which man can approach God.” For Aurobindo Ghosh the domains of politics, religion and faith were merging. He said, “I spoke once before with this force in me and I said then that this movement is not a political movement and that nationalism is not politics but a religion, a creed, a faith.

I say it again today, but I put it in another way. I say no longer that nationalism is a creed, a religion, a faith; I say that it is the Sanatana Dharma which for us is nationalism. This Hindu nation was born with the Sanatana Dharma, with it, it moves and with it, it grows. When the Sanatana Dharma declines, then the nation declines, and if the Sanatana Dharma were capable of perishing, with the Sanatana Dharma it would perish. The Sanatana Dharma, that is nationalism. This is the message that I have to speak to you.”

(The writer is a researcherwriter on history and heritage issues and a former deputy curator of Pradhanmantri Sangrahalaya)