Has the moment arrived for India to become a technology-transfer premised complementary manufacturing hub in Asia which can create value-added jobs? Intensifying great power rivalry is having a telling impact on the stability of China-centric global supply chains, forcing transnational corporations to rethink global sourcing strategies. It is precisely with this in mind that Prime Minister Narendra Modi in his address to a joint session of Congress during his state visit to America last month had declared: “When India and the USA work together on semiconductors and critical minerals, it helps the world in making supply chains more diverse, resilient, and reliable.” In a new paper, Ganeshan Wignaraja of the think-tank Gateway House iterates that the agreements on defence and critical technologies signed by Mr Modi and President Joe Biden, as well as the e-commerce investments promised by Amazon.com, are indicative of how India is being considered by the USA as central to new supply chains and its inclusion in the shift of existing ones away from China.

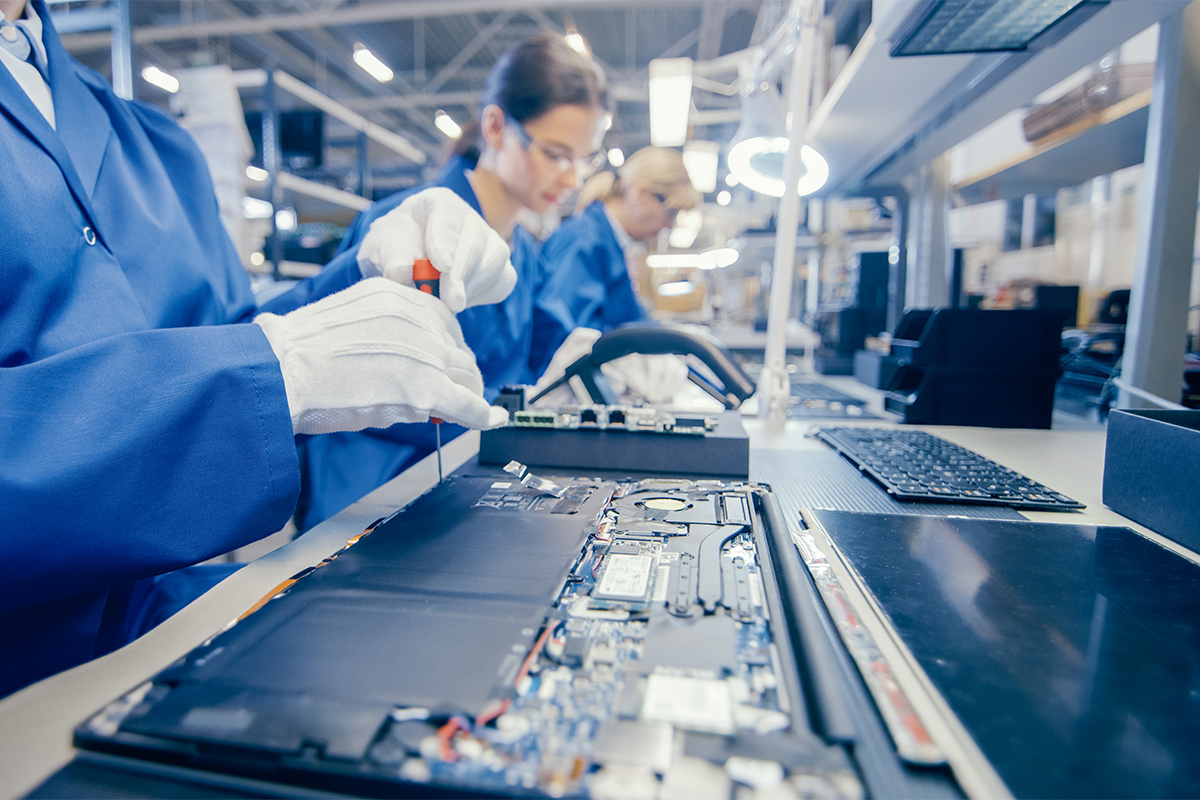

Recent investments in India for the production of Apple’s iPhone 14 and the Mercedes-Benz EQS electric luxury sedan suggest that supply chain pessimism about the country has started to fade. The argument being made is that since the end of the Covid-19 pandemic, both geopolitical and economic factors have coalesced in India’s favour. For example, India is a key target of the Indo-Pacific Economic Framework launched by Washington which seeks to de-risk, if not decouple, global supply chains from China and promote global sourcing from more strategically trusted supplier countries. Decoupling is already visible in flows of capital and technology, adds Wignaraja, as evident in the delisting of Chinese companies from US exchanges, or how American venture investment group Sequoia Capital has spun off its Chinese funds. The global risks of supply chains concentrated in mainland China and Hong Kong are underlined by recent World Trade Organisation data. Exports from the two markets, which together represent a fifth of world exports of intermediate goods, decreased 15 and 27 per cent year-onyear respectively, during the last quarter of 2022. Shipments from the USA, which accounted for 8.1 per cent of world exports of intermediate goods, fell 3 per cent, while those of Japan, with 4 per cent, fell by 13 per cent. This downturn, coupled with rising labour costs in China and the country’s trade war with the USA has forced multinational companies to think afresh. Yes, it is both costly and logistically cumbersome to shift supply chains. But longer-term profitability considerations, says experts, are influencing a trend of Washington actively encouraging the relocation of production to friendly countries, the much talked about “friend-shoring” policy of the Biden administration. Low wages, fiscal incentives, and improved logistics have meant that Southeast Asian economies such as Vietnam and Thailand have been bigger winners in supply chain shifting than India thus far. But there is no reason why India cannot reap the gains from the shift, especially in manufacturing sectors such as automotives, pharmaceuticals, and electronics assembly which provide well-paid, skilled/semi-skilled jobs. These are no garment sweatshops of yore.