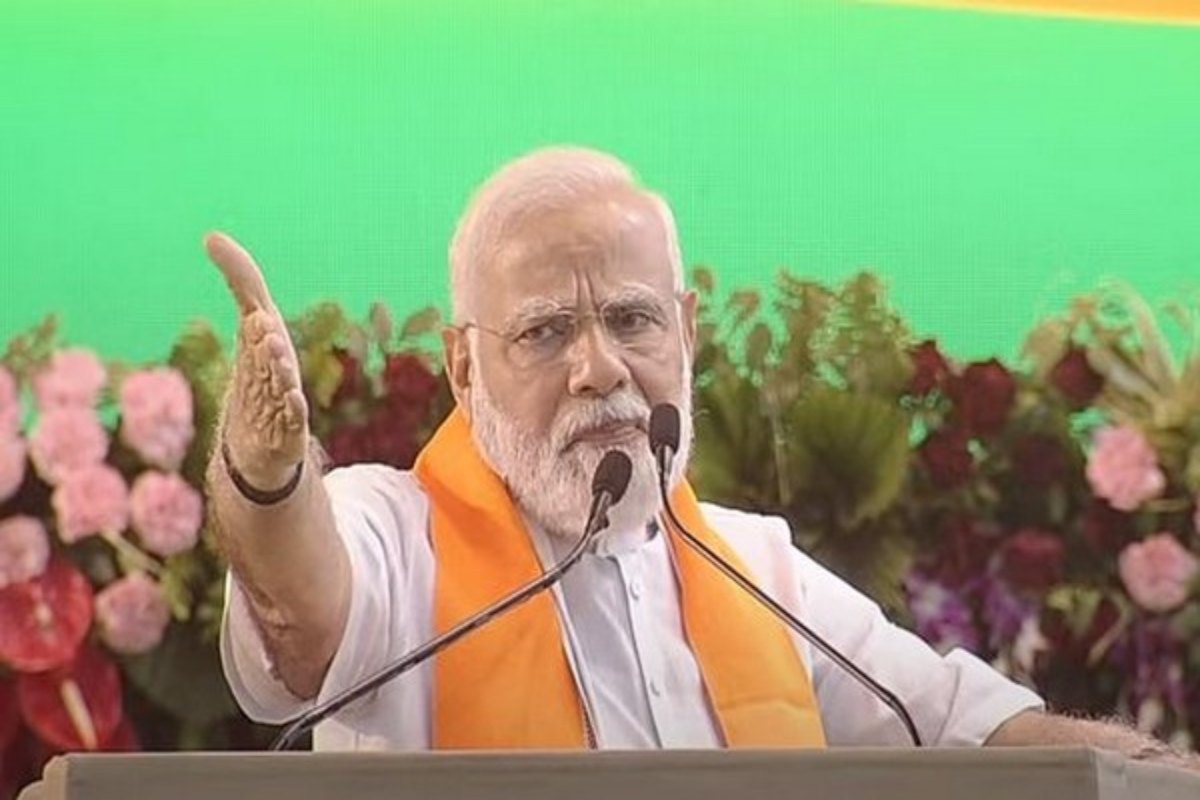

Prime Minister Narendra Modi raised the controversial issue of a Uniform Civil Code again this week while addressing BJP workers in Bhopal. Madhya Pradesh is going to the polls at the end of the year. It was not an off-the-cuff remark, as Modi had measured every word. Significantly, it was part of the Sangh Parivar’s core agenda.

Modi has overseen the other two parts of the agenda in the past nine years of his regime – building the Ram Temple in Ayodhya and revoking Article 370. Bringing a Uniform Civil Code remains on the table. There are various angles, such as political, legislative, religious, gender and Constitutional, to the question. The origin of the UCC dates back to colonial India. The British government submitted its report in 1835 and recommended uniformity in the codification of Indian law. Whether India needs a single law and whether now is the time to implement it remains a question mark.

Article 44 of the Constitution stipulates the state shall endeavour to secure a UCC throughout India for citizens. According to the Directive Principles of State Policy, the UCC is essential. Interestingly, Goa is the only Indian state that follows a uniform civil code. The Portuguese law of 1867 remained even after India annexed Goa. The Supreme Court asked the Centre why it was not extended to other states. Despite the codification of Hindu laws in 1956, a consensus on the Uniform Civil Code (UCC) is yet to be achieved in India. Various religious communities in India currently abide by their own distinct personal laws.

The UCC intends to unify all personal religious laws, encompassing marriage, divorce, property rights, inheritance, and maintenance, under a secular framework. The UCC has become more politically charged. Supporters and opponents are arguing on both sides.

Supporters believe that sooner or later, there must be a common law that applies to all religious communities. The BJP believes in bringing the UCC as soon as possible. Prime Minister Modi, while making a strong pitch for the UCC, said in Bhopal that the Constitution speaks of having equal rights. “If there is one law for one member in a house and another for the other, will the house be able to run? So how will the country be able to run with such a dual system?” the Prime Minister asked.

He argued that passing a uniform civil law would provide more benefits despite many differences and conflicts. The UCC would provide gender quality and remove different laws for different religions. Modi urged Muslims to see how the Opposition provoked and exploited them. The opponents, led by the Congress, fear the loss of minority votes.

They oppose it, as Muslims and other minorities do not favour it. Although some Islamic countries have adopted a common law for all, there has yet to be a consensus in India. The UCC is prevalent in France, the United Kingdom, the United States, and Australia.

However, Kenya, Pakistan, Italy, South Africa, Nigeria, and Greece do not have it. The issue had been debated in the Constituent Assembly. India’s first Prime Minister, Jawahar Lal Nehru, postponed a decision claiming, “I do not think that at the present moment, the time is ripe for me to try to push it (UCC) through”. Had the framers of our Constitution decided on the issue, there would have been no problem. Modi’s call for a UCC has provoked sharp criticism from opposition parties.

Many, including DMK, RJD, and JD (U) and AIMIM, led by the Congress, allege that Modi was diverting attention from bread-and-butter issues such as rising prices, unemployment and violence in Manipur. They note that there needs to be a consensus on the subject. The opponents point out that Muslims perceive the UCC as infringing on their religious freedom.

The Supreme Court highlighted the importance of a UCC in 1985, stating that it would help maintain national unity. In 1995, the Court recommended that a single law govern all citizens. In 2019, the Modi government expressed its commitment to implementing the UCC for all, following the Supreme Court’s ban on Triple Talaq, thus doing justice to Muslim women on divorce. Last month, the Law Commission of India began to examine UCC afresh. It solicited views and suggestions from the public.

In a secular country like India, UCC is significant to assure the majority that there is one law for all. Seventy-five years have passed, and it is time to consider it seriously in a country where 65 per cent are youth. However, it is the political will that is required. The Prime Minister must convene an all-party meeting to mobilise support for the UCC. With Assembly elections in some states and the General elections scheduled for next year, the UCC may have to wait for some more time.