UP govt to conduct grand roadshows in India and abroad for Maha Kumbh

Apart from this, approval has been granted for the purchase of 220 vehicles for the event.

The Election Commission of India conducts the presidential elections in exercise of powers vested in it under Article 324 of the Constitution of India.

Image source (census)

The people in India were witness to the maneuverings of two political formations ~ the party in power and its allies and of the opposition conglomeration ~ in selecting their nominees and their strategies in garnering support in the recent presidential election. For sure, they may have also wondered at some point if the choices and election exercise truly reflected their will. Yes, peoples’ keen observation of their representatives’ actions in discharge of each of the assigned roles is essential for strengthening of democracy. Not only should people closely observe but should make their opinion ~ approbation or rejection ~ explicit. A truly democratic set-up should provide an environment for this and the scope and the capacity to people for course correction when their elected representatives falter in their job; otherwise, the choices of vested interests prevail over the public interest.

Let alone the reflection or otherwise of people’s true will in voting, at least three anomalies in the election system, which are against the democratic spirit, are not being debated enough; they continue unchallenged election after election although the presidential elections are extremely important. Yes, the presidential position is crucial in that the constitutional architects carefully designed it for ensuring proper checks and balances in the governance and to guard against any autocratic trends of the elected government. Reverting to the three flaws, a quick recap of the presidential election is imperative since they are inherent to the system. The Election Commission of India conducts the presidential elections in exercise of powers vested in it under Article 324 of the Constitution of India.

An electoral college comprising the elected representatives of both houses of the parliament, elected members of assemblies of all 28 states and two union territories (National Capital Territory of Delhi and the Union Territory of Puducherry) which have assemblies elect the president (Article 54). The election is through the system of proportional representation by means of the single transferable vote and voting in a secret ballot [Article 55 (3)]. Now the three anomalies: First, 1971 is the population base till 2031. To ensure peoples’ representation from each state in proportion to the population, the constitution mandated that the vote value of each MLA be decided dividing the state’s population by total number of MLAs which again is divided by 1,000 to fix the vote value in 1,000 multiples; example: vote value of a UP MLAs is 208. It is obtained by dividing the state’s 1971 population (of 1971, not current) of 8,38,49,905 with 403, the number of MLAs, and again dividing the value thus obtained by 1,000. Needless to say, the value would be different if current instead of the 1971 population is taken.

Advertisement

Why 1971? The constitution (Article 55) originally mandated that the population base of the last preceding census of which relevant figures have been published be taken for calculating the MLA vote value (also implies MPs). But that was changed through the 42nd amendment to the constitution which had frozen the population reference year to 1971 till the year 2,000 which practically meant until after 2001 census data was available. The purpose of the then Congress government for such freezing was its population policy; it was feared that the states which strictly followed population policy would register slower population growth and therefore current year’s reference may result in a lower vote value meaning, a lower proportional representation to a performing state, which meant a disincentive for a good job whereas the states which failed to implement the population policy would register higher population and would get the benefit of representation incentive.

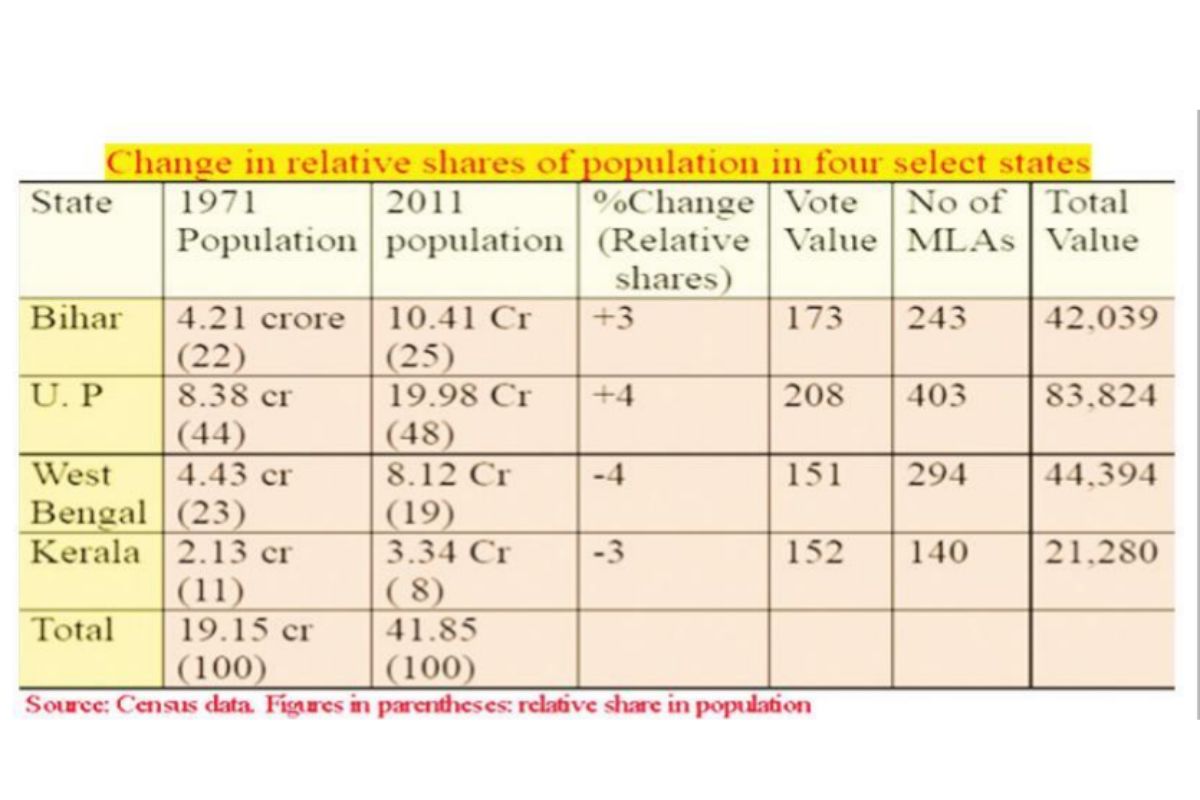

With this very same approach and purpose the NDA government through the 84th constitutional amendment extended the population reference year from 2000 to 2026 which means the same 1971 base continues till the 2031 census figures are published. Whichever the government and whatever its rationale, the persons born after 1971 do not get representation for no fault of theirs ~ they are not responsible for the ineffective population policy implantation. Is this not irrational, unjust and an outright undemocratic practice? Look at the relative shares in population growth of four select states, for example. Bihar (with highest population growth rate of 25.40 per cent in 2001-11 decade), UP (20.23 per cent growth), West Bengal (middle range growth of 13.84 per cent) and Kerala (least growth of 4.91 per cent) with a total 1971 population of 19.15 crore more than doubled to 41.85 crore in 2011.

The details show the relative fall in population growth in West Bengal to -4 and of Kerala -3 per cent between 1971 and 2011 against 3 and 4 per cent hike in Bihar and UP whereas the vote value of the MLAs remain unchanged at 1971 level at all these states (see accompanying chart). Second, the method of achieving proportional representation should be foolproof, not in some, but in all the 28 states and eight union territories. But that is not the case in all the Union territories ~ only NCT Delhi and UT of Puducherry are exceptions because they have assemblies. The state or territory with an assembly is represented in voting at two levels ~ through their assembly and parliament members whereas the UTs without assemblies represent only through their MPs. One example for greater clarity. The recently formed UT of Ladakh with Jammu and Kashmir reorganization in 2019, doesn’t have an assembly although its constituents ~ Kargil and Leh had MLAs when it was part of J&K who too were entitled to vote together with the MPs from the area.

Now the people have lost that privilege ~ no assembly, no MLA votes! Three, the values of M.P. votes are uniform although the all-India average population of an MP is 22.29 lac with wide variations. For instance, a Rajasthan MP represents 27.42 lac while that of Lakshadweep represents just 64,000 people ~ a mere 2.87 per cent of the all India average. Add to these three anomalies, the presidential elections at times are held without some assemblies’ participation. This time it was Kashmir where assembly is yet to be formed; this state could not participate in 1992, too. Also, there are other examples: Gujarat (in 1974), Assam (in 1982) and Nagaland (in 1992) could not participate in the presidential elections as their assemblies were in dissolution. Technically it was correct because elections to the president’s position were to be held before the incumbent president’s term ends [ Article 62 (1)]. But is it not the duty of the government to ensure the timely assembly elections so as not to exclude a state’s representation?

A version of this story appears in the print edition of the September 3, 2022, issue.

The writer is a development economist and commentator on economic and social affairs

Advertisement