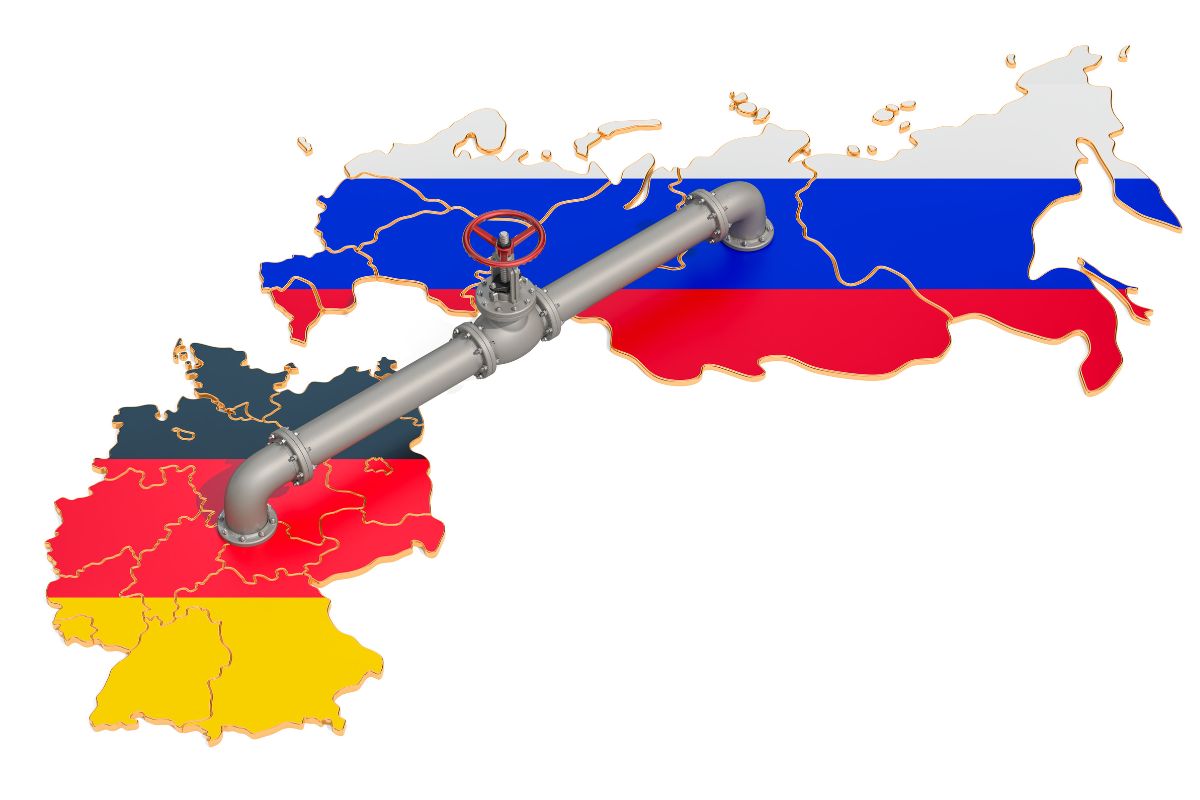

In the absence of a unified European strategy on energy security, Germany was merrily sourcing cheap Russian gas to enhance its global competitive advantage before the Ukraine war. Now, Moscow is making Germany (and Europe) pay the price for this over-dependence. When the 10-day “scheduled maintenance” of the Nord Stream 1 pipeline ends on 21 July, will the Russian state-controlled gas exporter Gazprom resume deliveries? Or will, to use the evocative phrase coined by commentator Constanze Stelzenmüller, a “gasectomy” be performed on Germany by President Vladimir Putin? Nord Stream 1 supplies 58 per cent of Germany’s annual gas needs. A couple of weeks ago, after Russia reduced supplies by 60 per cent, Berlin triggered the second stage of its national gas emergency plan ~ one step away from gas rationing.

Germany also sources gas from Norway, the Netherlands, and Belgium but ~ given that Russia has not redirected its gas headed for Germany via alternate routes ~ Berlin is hard-pressed to fill its gas storage facilities to ensure reserves for the North European winter. According to Stelzenmüller, Germany’s threedecade-long trade surplus turned into a deficit earlier this month driven by the rise in gas prices. Europe’s largest economy has created its wealth in the main by energy-intensive industries, whose import costs have soared. Inflation is at a record high, fears of a recession are very real, and the euro is at parity with the dollar for the first time in two decades.

Take cheap Russian energy out of this anyway dire economic situation, and the writing is on the wall. The Kremlin is making Germany and the rest of Europe pay a massive economic cost for supporting what it sees as the Washington-driven expansionist agenda of the North Atlantic Treaty Organisation. In Germany, where the impact of Russia turning the screws is being felt most acutely, the talk is of bringing “dirty” coal plants back online and telling people to take shorter showers.

The government is trying to streamline energy procurement and environmental restrictions are being eased to build fixed liquefied natural gas terminals. Authoritarian leaders from West Asia, with whom Berlin had previously interacted with noses pinched, are being wooed in search of alternative gas supplies. There are lessons here for the Global South, including for a section of influential policymakers in India. Swallowing the whole Western narrative on the environment and democracy is not without its perils. As is evidenced from the solutions being attempted by German leaders to fix that country’s gas problem, it’s always about the economy. While it would not do to be reductionist about it, the fact remains that economic concerns will always be paramount for any sovereign country.