Securing India’s coast through multi-agency ops

The importance of coastal security was acknowledged long ago. In the evolving world, types of threats have diversified.

Frankly, very often the adopted land is much more appreciative than the homeland.

In the 1960s, India came to be known as the begging bowl of the world. Famine had made the country unable to feed its own people. Lal Bahadur Shastri was not one to tolerate global insults.

He started the green revolution because of which the country’s granaries are full today. India aspires to be a world leader. When floods ravaged Pakistan in 2010, it gave the country $25 million.

Billions of lines of credit have been extended to countries like Bangladesh. India has spent over $3 billion building up Afghan infrastructure which is slated to fall into the Taliban’s hands there once the Americans leave and the American propped-up Ghani government collapses.

Advertisement

The Afghan investment may or may not prove a wise investment, but it certainly earned India considerable goodwill in the corridors of the powers that be that still really and principally matter in the world, those of Washington, D.C. India gave the impression that it was punching above its weight, all in the cause of winning a UN Security Council permanent seat.

But the world took from India, and no perma-seat came. Still India didn’t lose heart. It would contribute heavily to UN peacekeeping missions. It would become a net donor of aid (not counting developmental aid).

It would refuse foreign aid for floods and earthquakes and tsunamis. India had become self-sufficient. It would give aid to an adversary like Pakistan but refuse to accept it from it.

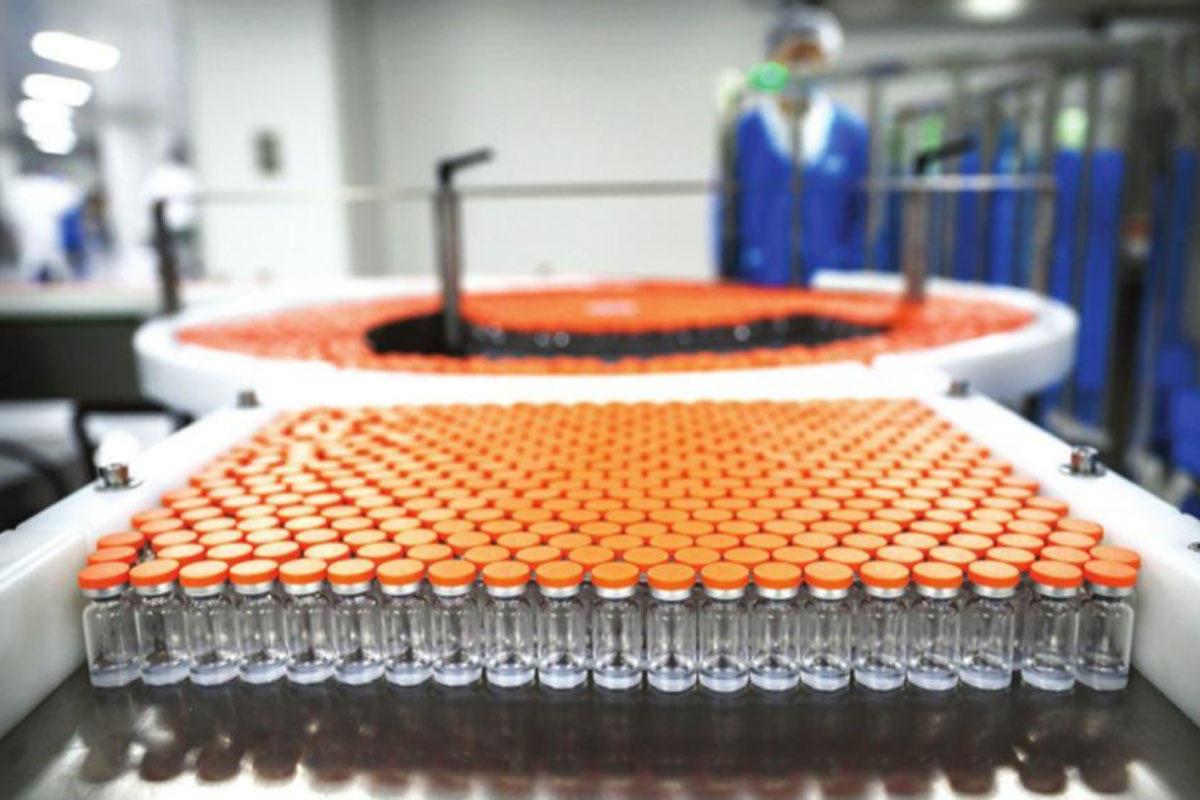

Therein it appeared a bit churlish, but when has Indian foreign policy towards its adversaries not looked a bit churlish? The pandemic struck the world in early 2020, and India launched its Vaccine Maitri programme, in effect vaccine diplomacy around the world. It crowed that it was the pharmacy of the world and the world’s biggest vaccine maker.

It sent some medicine to places like the US. Through draconian lockdowns, it curbed the virus in its country. Then it let its guard down.

The virus attacked 1.4 billion people. Images the world over were of cremation grounds packed to the gills. India did not know where to look.

Initially the US proved petulant in providing raw materials for vaccines, but when the magnitude of the crisis hit home, reversed stand. People in the West cancelled their plans to visit India for a year. Billionaire Indians fled to London and Dubai for safety. Note that when the pandemic hit America, billionaire Americans had only sought succor in remote American states like Wyoming.

Our billionaire class, they are a class apart. Our pharmaceutical companies who were going to supply the whole world with vaccines could hardly meet even a pittance of the demand in India. It was an all-round shameful effort. Has India learnt anything from the crisis? Will it keep relying on chalta hai and jugaad and meander around as a self-declared world power? Will it finally instill a work ethic in its people that the prime minister of the country has? Now we are saying that we will ramp up vaccine production manifold to deal with future pandemics.

Well, pandemics like Covid and the Spanish flu of a hundred years ago come only once in a century. More likely when the crisis abates in India, everything will be hunky-dory as before. I am reminded of a friend who before his IIT exam said that he wouldn’t prepare for it that year but wait for the following year.

The future always looked bright to him. He was always willing to sacrifice the present. He never made it to an IIT. If not now, when? That is the question that Indians must ask themselves. The reality that Indians are not willing to accept is that the world has left India behind. It is not only America and Europe.

It is not only China, which is leaving the whole world behind. It is not just countries like Thailand and Malaysia and Indonesia. Just take a look at the skylines of the capitals of each of these respective countries: Bangkok, Kuala Lumpur and Jakarta.

It is even South Asian countries like Sri Lanka and can you believe it, Bangladesh.

The pandemic has exposed India as a state, which since Independence, has not been able to provide its people adequate water and food and healthcare and mobility. The prime minister appeals from the ramparts of the Red Fort to curb population explosion, which he beseeches is nullifying all the gains that the country makes, but few bother to pay heed.

Take his pearls of wisdom from one ear and take them out the other. Yes, a few, very few have become rich, uber-rich and they are the ones who consider their lives and the lives of their loved ones the most precious in the world.

They are the ones jetting off to London and Dubai to seek refuge from the pandemic. India’s diaspora is one of the largest in the world at around 30 million.

The diaspora comes to India’s need whenever India falls into trouble, but the diaspora is suffering from donor fatigue. Firstly, the elite classes in India consider the diaspora as mercenaries who left India for greener pastures abroad. Then the diaspora also feels obligated to help its adopted lands in their own time of trouble.

Frankly, very often the adopted land is much more appreciative than the homeland.

The homeland just expects without giving acceptance. The adopted land does not expect as much and gives acceptance even for a little help. The pandemic must change the mindset of Indians in India. But will it? I doubt it.

The writer is an expert on energy and contributes regularly to publications in India and overseas.

Advertisement