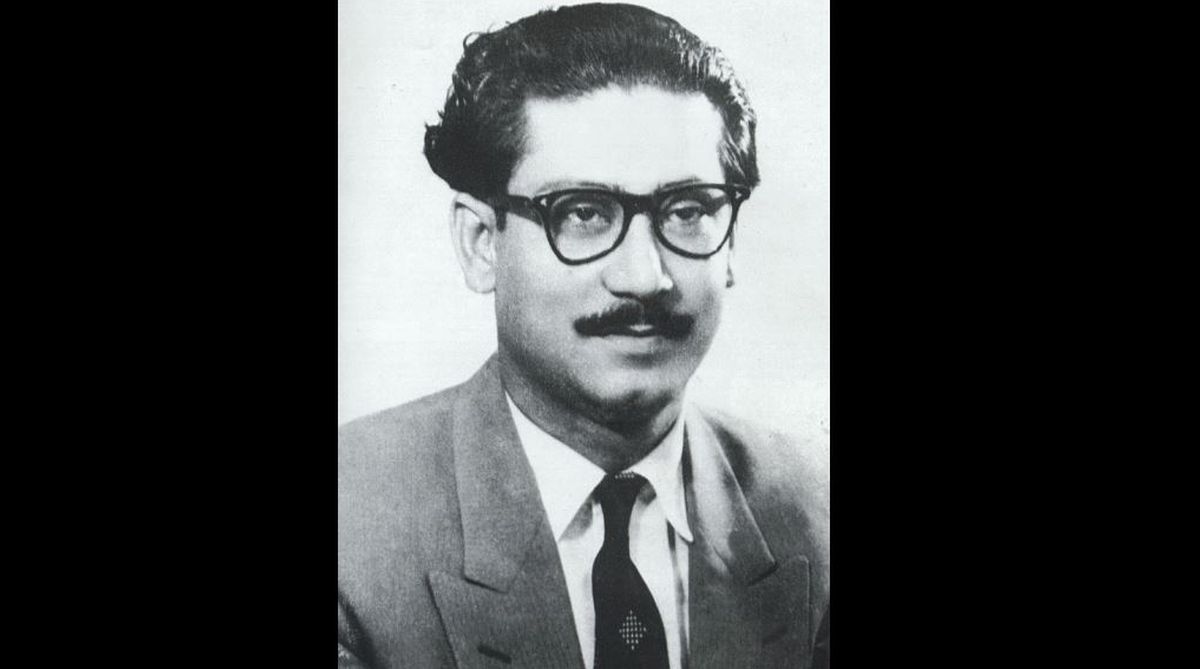

Prime Minister Narendra Modi at a virtual summit with his Bangladeshi counterpart, Sheikh Hasina, recently released a commemorative postage stamp on the occasion of the birth centenary of Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman. India issuing a stamp to honor a foreign leader is a rarest of rare events and in the past such stamps were only issued on the death centenary of Abraham Lincoln (1965), in honour of Martin Luther King Jr. (1969) and on birth centenaries of Vladimir Lenin (1975) and Ho Chi Minh (1990). A contingent of the armed forces of Bangladesh participated in the Republic Day Parade at New Delhi to z commemorate 50 years of the Bangladesh Liberation War. Only on two earlier occasions had a contingent of a foreign country participated in the Republic Day celebrations. Prime Minister Modi is likely to visit Dhaka in March to participate in the Golden Jubilee celebration of the liberation of our eastern neighbor. All these events demonstrate how India values the principles that Bangabandhu stood for and India’s priority in strengthening friendship with Bangladesh.

To many of that generation who had witnessed the bitterness of partition of this sub-continent, these gestures of India may appear to be counter intuitive. Sheikh Mujib as a student (1942-47) of Islamia College of Calcutta (now known as Maulana Azad College) was an activist of Pakistan movement and even at that age he emerged as a powerful youth leader in Bengal politics because of his proximity to the then premier of Bengal, Huseyn Shaheed Suhrawardy (who in 1956 became the Prime Minister of Pakistan). After partition, Mujibur Rahman returned back to Dhaka.

When Muhammad Ali Jinnah declared in 1948 that Urdu would be the only State Language of Pakistan, protests broke out amongst the Bengali speaking majority of Pakistan led by Sheikh Mujib. Within few years Sheikh Mujib turned out to be the de-facto leader of his people in spite of the presence of many senior leaders who played significant roles in pre-partition politics and in governance of Pakistan after partition viz. A. K. Fazlul Haque, Sir Khawaja Nazimuddin, Suhrawardy, Maulana Bhasani, Nurul Amin and Sahibzada Mohammad Ali Bogra. In less than a quarter of a century, Sheikh Mujib succeeded in making his people free from Pakistani subjugation.

Was it a case of complete turnaround of the ideology of Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, before and after partition or was it an example of a leader who evolved over time? Perhaps it was neither. Most of the leaders of Bengal Provincial Muslim League in pre-partition days did not believe in the two-nation theory of Muhammad Ali Jinnah, yet they wanted a separate Muslim State of Pakistan. The meaning of Pakistan(s) was deliberately kept so vague by its proponents that it meant different things to Muslims in different regions. For the majority of the people of East Bengal, language identity was stronger than religious identity. If their leaders had really believed that the Muslims of the sub-continent constituted a different nation, Shaheed Suhrawardy would not have approached Jinnah or Bengal Congress leader Sarat Chandra Bose with the idea of forming a third country: an undivided Bengal at the time of partition. To them partition of Bengal was only the second-best solution, a strategy to achieve a higher goal. For leaders like Mujib, inclusion of East Bengal in Pakistan was only an intermittent stage to realize the goal of an independent nation, predominantly based on Bengali culture as opposed to Islamic culture but where the reins would be in the hands of the majority Muslims. Pakistani rulers, however, looked at the people of East Bengal with contempt as they were perceived to be culturally close to the Hindus, their language was more akin to Sanskrit. More the Pakistani rulers tried to Islamize the culture of East Bengal (renamed as East Pakistan in 1955), it made the job of Mujib easier. Bengali identity of people gathered strength and their attitude towards the rulers hardened. That’s how within two decades of formation of Pakistan, Sheikh Mujibur Rahman turned out to be the supreme leader of the entire population of East Bengal, irrespective of religion and varied ethnicity of people living there.

In 2004, BBC organized an opinion poll to find out the greatest Bengali of all time as perceived by Bengalis at that time. Bengalis from India, Bangladesh and overseas were all expected to participate in the poll. We should not assign much importance to such polls. At the same time, we cannot overlook the fact that Bangabandhu was voted to be the greatest Bengali of all time and he polled more votes than Rabindranath Tagore! One may, however, legitimately ask if a people’s leader like Sheikh Mujibur Rahman was there what made Hindu population in East Bengal to dwindle from 28 per cent in pre-partition days to 22.05 per cent in 1951, 18.5 per cent in 1961, 13.5 per cent in 1974 (after formation of Bangladesh), 12.13 per cent in 1981, 10.51 per cent in 1991, 9.2 per cent in 2001 and 8.96 per cent in 2011? In order to understand this phenomenon, we need to go deep into the politics of Bangladesh.

There are two strong parallel streams in Bangladesh: the liberal democrats enlightened by the spirit of freedom struggle (muktijuddho) whom Sheikh Mujib stood for. The other constitutes the conservative elements who might or might not have supported Pakistani rule but always accused the liberals of being Indian stooges. Hindus primarily left East Bengal not so much because of religious persecution but because of intimidation by this second stream in social life of that country. It is difficult to prove such intimidation but those who have faced it know it well. The struggle of Sheikh Mujib in his time and that of Awami League today is primarily against identity politics promoted by this second stream.

The politics of India in the aftermath the partition was also responsible to a great extent for the dwindling Hindu population in Bangladesh. In the provincial elections of 1946, Bengal Provincial Muslim League won 113 out of the 117 Muslim electorate seats, whereas Congress with predominant support of the Hindus in 78 General electorate seats, won 86 seats in total. Muslim League formed the Government led by Suhrawardy. In the following year, after the partition, 141 legislators representing constituencies that fell in East Bengal were included in the East Bengal Legislative Assembly and 35 of them were elected on Congress ticket. But the Congress leaders of the East migrated to Calcutta instead of leading their followers in establishing the rights of minorities in newly formed Pakistan. Hindus in East Bengal (today’s Bangladesh) were rudderless after partition and were stunned by the suddenness of the event. They felt as if they had become ‘foreigners’ in their homeland and followed their leaders in leaving the country with or without provocation.

The most important contribution of Sheikh Mujibur Rahman was just not to give the clarion call for liberation but to develop the “spirit of muktijuddho”, to make all his people dream of establishing a society based on liberal values. But his journey in realizing this dream remained largely unfinished because of his assassination within three years of his coming to power. After his assassination in 1975 and after assassination of all top-ranking leaders of his party later in the same year, his daughter Sheikh Hasina had to build up Awami League from scratch and she had to struggle hard to revive and to keep alive the spirit of freedom struggle by isolating the fundamentalist elements in society. It’s an eternal battle. India by honoring Bangabandhu in a year when Bangladesh is going to celebrate 50 years of its independence, salutes this spirit that Sheikh Mujib had created, which is still the driving force of society under the leadership of his daughter.

The writer is a former civil servant