Kangana says THIS about Diljit Dosanjh’s meeting with PM Modi

Kangana Ranaut discusses her admiration for PM Modi, addressing her failed attempts to meet him and expressing a desire for a future conversation about the arts.

All of this came on a day, moreover, that the second phase of the Malabar Exercise got underway in the northern Arabian Sea with the navies of all Quad members ~ India, US, Australia and Japan ~ participating in strength.

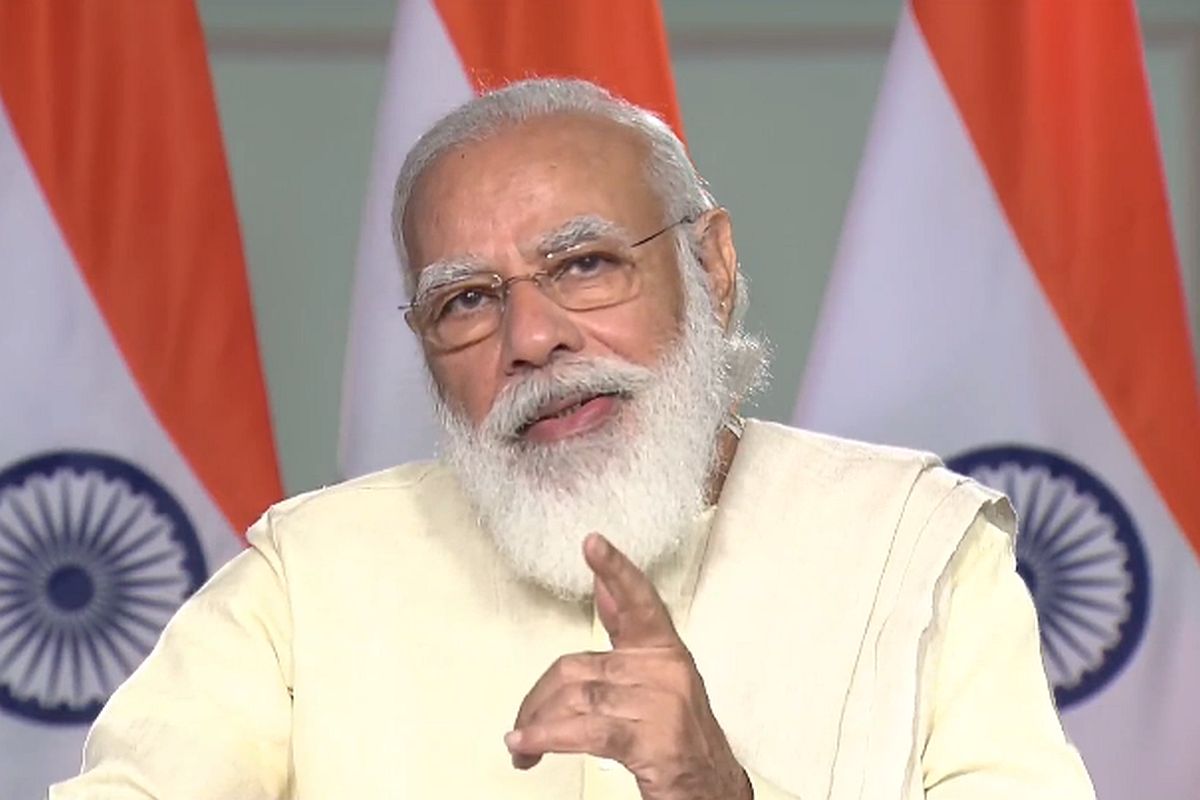

(Photo: Twitter/@BJP4India)

That the global balance of power and strategic architecture is very much a work in progress ~ and India is watching events unfold keenly without committing to a particular course of action ~ was brought home by two interconnected but separate events over the past few days.

On Tuesday, Prime Minister Narendra Modi addressed the 12th BRICS summit and devoted the bulk of his speech to what may be termed political and security concerns while calling for cooperation at a humanitarian-scientific level in the fight against the Covid-19 pandemic.

Advertisement

Ironically, geopolitics was his dominant theme despite BRICS being conceived essentially as an economic bloc of developing countries ~ Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa ~ as Mr Modi headlined the need to fight terror and those supporting terrorism, underlined his support for a robust BRICS Counter-Terrorism Strategy and highlighted the need for UNSC reform.

Advertisement

All of this came on a day, moreover, that the second phase of the Malabar Exercise got underway in the northern Arabian Sea with the navies of all Quad members ~ India, US, Australia and Japan ~ participating in strength.

Obviously, China is not unaware of the messaging either in the PM’s speech at the BRICS summit or by the exhibition of military prowess on the high seas. A couple of days earlier, on 15 November, the world’s largest trade agreement, the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP), was signed by 15 Asia-Pacific nations including China, just over a year after Mr Modi surprised members of the RCEP by choosing to opt out of the trade deal in Bangkok.

Strongly backed by Beijing, the RCEP will play a pivotal role in China expanding its geography of trade and thereby adding even more muscle to its already considerable economic heft. When India had walked out of the RCEP talks in November 2019, the understanding was it would continue to negotiate its issues of concern including greater market access for Indian goods and the base year for tariffs/duties.

The short point today, however, is that the economic argument, whether for or against, is no longer the key determinant for New Delhi. Entering a mega trade deal with China in the driving seat is, as things stand, unfeasible. Some argue that if Asean nations, Japan and Australia can successfully compartmentalise economic ties from political and security concerns, so should India. After all, joining the RCEP ~ especially if key concessions can be extracted ~ would make a lot of sense as India’s products and services would have easy access to a massive market and its companies could finally achieve scale.

But those making this argument elide the fact that these countries have limited geostrategic ambitions and their economies are already deeply intertwined with the Chinese supply chain. It remains a pipedream to expect Sino-Indian economic co-prosperity with geopolitics in flux. In fact, it would be foolhardy to rush into a legally binding international trade agreement without a clue about the strategic intent of the prime mover behind it. At least for now

Advertisement