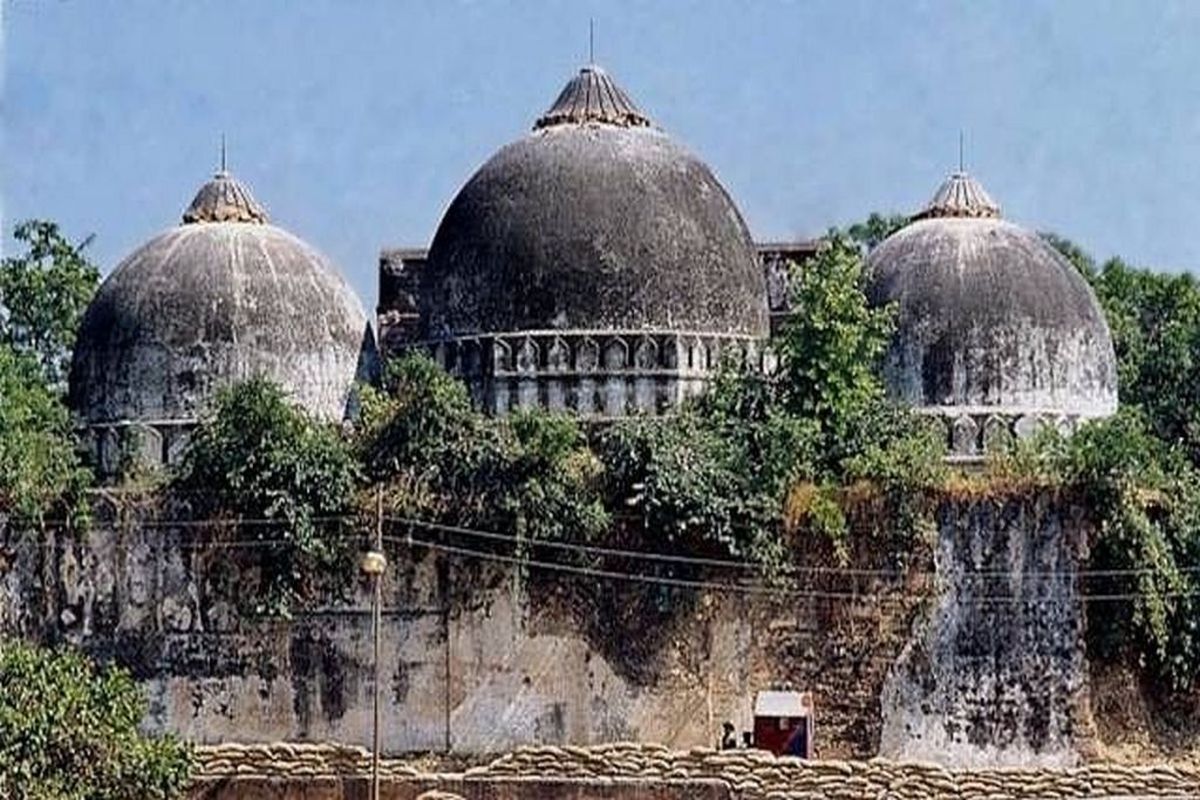

The verdict by a special court in Lucknow acquitting leaders of the Bharatiya Janata Party and of groups affiliated to it in the demolition of the Babari mosque in Ayodhya on 6 December 1992 is a sad reflection on the quality of the investigation by the prosecuting agency, but equally on the judiciary.

For in concluding that the demolition was a spontaneous act by several thousand people gathered on the site that fateful date, the court refused to take cognisance of mountains of evidence that suggested the contrary. For refusing to place credence on newspaper reports, on the ground that originals were not submitted; video footage, on the ground that it had not been forensically validated and photographs, on the ground that negatives were not supplied, the judge may be accused of being overly technical.

But how does this reflect on the Central Bureau of Investigation which even with its record of botching up sensitive cases ought to have anticipated these basic objections? This newspaper, for instance, had in the days just before the demolition, published despatches from a reporter who had disguised himself as a kar sevak, joined a contingent from Delhi to Ayodhya, and had participated in drills on how to use various tools to pull a structure down before returning on the eve of the demolition to file his reports.

The fact that such training took place flies in the face of the conclusion that the demolition was a spontaneous act. At best, the judge might have raised questions on the proof offered to suggest that some leaders either conspired to cause the demolition or exhorted those who carried it out. But to reach the conclusion that none of those accused was involved in bringing kar sevaks to the site, or in preparing them for the demolition, or both, the judge would appear to have erred grievously, an error that may have been exposed had television channels replayed footage from 1992 which the government forbade them to.

But beyond quibbles on the quality of this judgment, greater concern must be voiced about its consequences. For it will widen the schism in Indian society ~ one that was created 28 years ago with the demolition ~ and heighten fears that other mosques, principally those in Varanasi and Mathura, will be targeted next.

Certainly if an egregious act of violence carried out in full public glare in 1992, when the BJP did not control the Union government, could result in the perpetrators getting away scot free, it will only embolden those Hindu groups that three weeks ago revived the demand for the Varanasi and Mathura mosques.

This is a slippery slope, and it will require sagacity and skill to both defuse the tensions that the verdict will arouse and to ensure that hotheads ~ on either side of the communal divide ~ do not use it as an opportunity to inflame passions. We lived in troubled times even before the Lucknow verdict; now, our troubles may be growing.