Nagaland govt to disallow ‘Gau Mahasabha’ in Kohima

The Nagaland government on Wednesday announced that it would not allow the holding of ‘Gau Mahasabha’ and Gau Dhwaj Sthapana Bharat Yatra in Kohima on September 28.

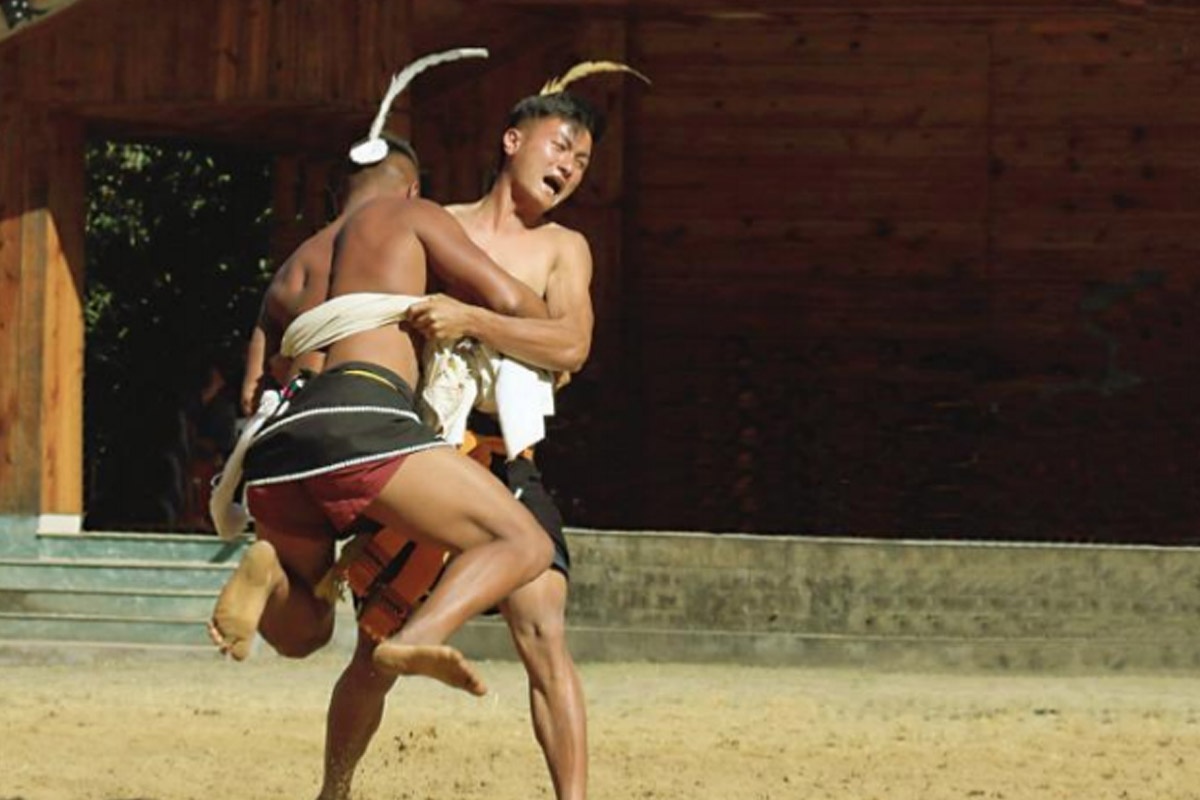

A physical duel has traditionally been an important tool for conflict resolution in Naga society

What football is to the average Englishman, baseball or basketball to the American, ice hockey to the Canadian, and cricket to many Indians, wrestling is to the highland Naga. Especially for the Tenyimia Naga (a cluster of Naga tribes spread across Nagaland, Manipur and Assam), it is a game that is always also more than a game; it stirs up intense passions that swirl around sentiments of pride and pleasure, status and standing, conquest and domination, a topic of endless speculation and conversation, and the carrier of a distinct heritage locally.

George Orwell famously called sports “war minus the shooting”. From this angle, sporting contests channel radical nationalist sentiments into a competitive, agitated but distinctly non-violent confrontation. This is what historian Eric Hobsbawm too observed. Between the World Wars in Europe, he wrote, international sports gradually ceased to be the pastime of a middle-class public, or the object of integrating different national components of states and empires (such as the British Empire Games), and increasingly turned into “the unending succession of gladiatorial contests between persons and teams symbolising state-nations”; an as if war, that is, between rivalling nations with patriotism and pride at stake. Or, for that matter, as an expression of national struggle, as in the movie Lagaan in which Indian villagers defeating a team of Britishers in a game of cricket resulted in colonial officials evacuating their local cantonment and departing, seemingly forever.

However, rather than the symbolic pseudo-wars between rival nations, among the Naga, wrestling traditionally functioned as a safety valve to release social tensions internal to the village community, mostly between clans and khels (village wards) but also between antagonistic individuals. My broader argument is this – among the (Tenyimia) Naga the social significance of wrestling lies in its traditional capacity to temporarily absorb, channel and deflect the internal rivalries, irritations, and disputes that occasionally threatened the cohesion and survival of the village community. What is more, wrestling constituted a Naga annotation in themselves, in the sense that wrestling both communicated pivotal cultural values – of strength, bravery, and pride – and embodied kinship and social networks. As such, wrestling carried out important social and political work.

Advertisement

Even more than symbolic fights, though, winning or losing a wrestling match could have real social consequences, which were commonly acknowledged across Naga villagers. Disputes over property, for instance, could be settled with a wrestling contest and the contender ending on top — literally so by working his opponent to the ground — being recognised as the disputed property’s now undisputed owner. Interpersonal dislikes and disagreements also found expression during village wrestling contests with those having a “problem” in real life challenging each other to a fight. Not infrequently, such animosity and its social translation in wrestling duels reproduced themselves across generations, from father to son to grandson challenging their social equivalents of the rivalling family. Those who won would assert their superiority in social life, at least until the time of the next wrestling contest.

Clans competing over status and sway within the Naga village, too, could be ranked in terms of the wrestling achievements of its strongest men, who were seen as magnifications of the clan’s self. In preparation for wrestling, selected men were temporarily excluded from agricultural toil and fed enormous amounts of rice, rice-beer, and meat of many kinds to build their bodies, and to whose expenses the entire clan would contribute. Recounted a Chakhesang Naga elder and former wrestler, “In my time, I could eat two chickens a day and drink rice-beer from morning till evening in the weeks leading up to wrestling. If I said my stomach was full my clan members would scold me and force me to eat more.”

If anything, the energy and expenses invested in “building” a wrestler’s body attests to wrestling’s significance in traditional Naga village life. Read against a broader Naga cultural canvass, wrestling reflected a wider traditional principle that saw physical strength as virtue; that accepted that “might” connoted certain “rights”. So important was the value of physical strength that, during the early beginnings of formal education, quite a few families expressed reluctance to admit their children into village schools, fearing that long days of sitting would make them too weak to wrestle.

In match days, the physical strength on display, boisterousness of the wrestlers, verbal challenges that went back and forth, and the sheer adrenaline all around gave wrestling contests – which were ever the mass spectacles – an appearance of a violent conflict, one that was fought as though about life and death. However, when the dust of a wrestling tournament had settled and bruises and other small injuries began to heal, what had occurred was not just a physical duel. In effect, the tournament had released social tensions and deflected the potentially more serious violence such tensions could otherwise result in, so that a cohesive and clear-cut sense of village unity and solidarity could be restored. At least temporarily.

In deep history, the channelling of social tensions through wrestling was a culturally directed possibility within Naga villages. It was not a selfevident possibility between Naga villages, however. In fact, one way of reading Naga political history is in terms of seemingly unending intervillage feuds, vendettas, raids and retaliations over power, status and dominance in the hills. Consequently, the social distance that existed between villages was often considered to be too large to be resolved through the social ritual of wrestling.

Naga wrestling’s more recent history reveals the enlargement of its social catchment. As a case in point, among the Chakhesang Naga, the period between 1940 and the early 1970s witnessed three major masswrestling events between two large, historically antagonistic villages, and so on neutral grounds. The explicit aim was peace-making. As one participant recalled, “Before each match, the two wrestlers had to introduce themselves and promise that whenever the opponent would come to his village, he would find shelter and food, including meat, in his house.” In this way, the equation between wrestling and conflict-resolution gradually expanded from an intra-village affair to inter-village contests of comradery.

Wrestling’s enlargement was to continue, and wrestling tournaments are today a regular occurrence at village, range, district and state levels where they draw large and enthusiastic crowds and advertise cashprizes and – at the state level – government jobs to those crowned champions. And this year, the Nagaland Wrestling Association celebrated its 50th anniversary through a golden jubilee tournament with the Nagaland chief minister as chief guest.

There is a flip side to Naga wrestling’s professional and, some lament, commercialised institutionalisation. Some of its earlier inner workings as a form of conflict-resolution receded into the realm of forgotten cultural practices. Whereas in the past, individuals, families or clans in a dispute might say, “Wait, we will face you in wrestling”, today these social groups are more likely to say, “Wait, we will face you during the next election”. The social outcome of this shift is very different. If wrestling contests traditionally functioned to restore and regenerate a sense of village community, elections don’t resolve divisions but intensify them, making it a more corrosive form of working through interpersonal and social differences.

The writer is a social anthropologist and teaches in the department of social sciences at Royal Thimphu College, Bhutan

Advertisement