Assam cabinet announces new holidays, financial aid, and cultural honours

The Assam cabinet has rolled out a series of decisions impacting state employees, cultural recognition, and welfare schemes.

With their generous annual leave allowance (28 – 35 paid holiday days) and their comfortable salaries – they are indeed the fortunate few. Americans are lucky if they get more than 10 days paid holiday per year and Asians are the workaholics of the world. Singapore heads the table for the least number of paid holidays in a year (18 days including public holidays).

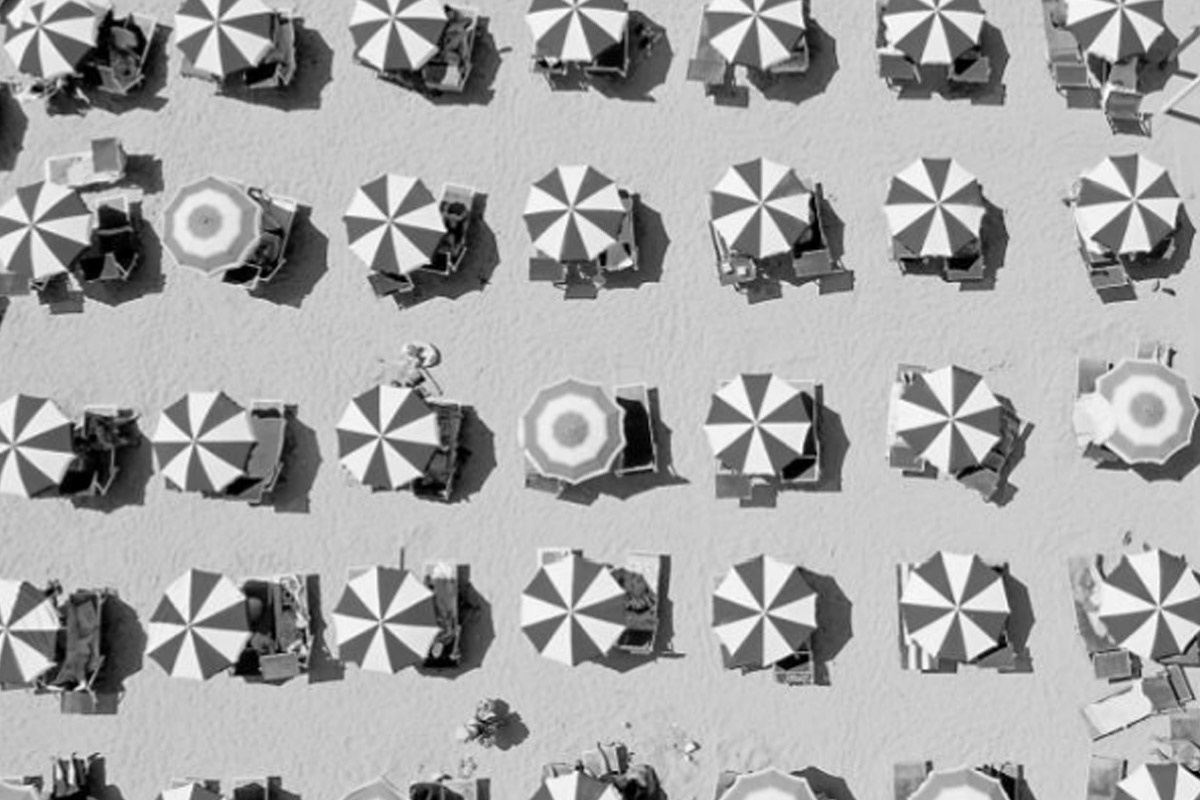

It is September and Europe is on the move. To beaches, to sun-soaked islands, to the countryside – anywhere but home. Nothing seems to stop holiday seekers. Not the patchy flights along agreed air corridors, not the threat of the pandemic hanging in the air and not even the dire warnings of quarantine as they return home from countries which are seeing a second wave of the virus. Europeans (Brits included as of now), take their summer holidays very seriously indeed.

Every summer, journalists declare August as ‘the silly season’. There is no serious news worth covering – even the political leaders are on vacation. As I write this in August, Boris Johnson is in Scotland, Macron is off jet-skiing on the Mediterranean coast and Angela Merkel has declared that she will be taking a holiday in Germany this year instead of her beloved Tyrol mountains in Italy – but holiday she must!

Advertisement

So what is it about a summer break that makes it so necessary for wellbeing? What makes sun and sand essential commodities? Surely they are not as vital to human life as say, water and air? Yet the way Europeans go about it, they seem to be. With their generous annual leave allowance (28 – 35 paid holiday days) and their comfortable salaries – they are indeed the fortunate few. Americans are lucky if they get more than 10 days paid holiday per year and Asians are the workaholics of the world. Singapore heads the table for the least number of paid holidays in a year (18 days including public holidays).

Advertisement

How long this European addiction to travel for holidays lasts remains to be seen. As the social welfare state crumbles and societies age, automation will replace well-paid manual jobs and it is likely that holidays will become less affordable. The lingering effects of the pandemic and growing environmental concerns will also make foreign holiday trips unethical and unsafe as we head towards a more uncertain future. The glamorous foreign summer holiday may have had its day – so to speak. But while it lasted, it has fed social media with images of bronzed bodies on beaches, fuelled envy and longing amongst the stay-at-homes and put lots of money into a lot of airline and hotel balance sheets.

Now where do we Indians fall along the whole summer holiday spectrum? Sun – no thank you. We get enough of it round the year. Sea – despite our long coastline, sea sports and beaches are few and far between. Goa yes, but even Goa is at its best in December when the temperature is cooler by a few degrees. Certainly a few decades ago, summer was a sleepy, torpid time of year when the sun beat down incessantly and schools were closed. There were no air conditioners to diffuse the heat, no television to alleviate the boredom, no computer games to divert the monotony. But wait a minute, I am imposing these negative connotations with hindsight. If anyone had ever asked me as a child if summer holidays were boring – I would have wondered what emotion they were talking about. I certainly didn’t recognise the feeling!

As children, armed with our curious minds and lots of time on our hands, we made the most of our summer. School books were closed and novels opened with trembling excitement. Parental supervision waned as the demands of homework lessened and mothers themselves took it easy – allowing themselves a precious afternoon nap. I remember reading all the racy novels of Harold Robbins found in my mother’s book shelf one summer holiday without anybody realising the mismatch between my reading age and my emotional maturity. I survived without any permanent psychological damage – I think!

Yes summer was a very special time of year but the difference was dictated by the slowing of pace, the change of season (hot to hottest) and the change of rules (we were actually allowed to pack our school books away and go for sleep-overs to cousins’ homes). There were occasional holidays that entailed going out of town – normally to a relative’s home and of course all the excitement associated with those – but it was mostly about making the most of one’s own home with more time on our hands. If my childhood in India taught me one thing – it was that holidays need not be about a change of place, they can be equally refreshing with a change of pace, an awareness of seasonal delights and a willingness to explore one’s own environment.

So there were summer smells and summer sounds to enjoy. There were summer tastes and summer rituals to rediscover each year – where was the time to get bored? I still remember the taste of cool matka or surahi water in my mouth – sweet as the earthenware it cooled in – and at just the right temperature to gulp down thirstily, fresh from a competitive seven stones game in the garden. For more gourmet drinking, there were the various summer-beating sherbets – from the rose flavoured Rooh Afza to the sweet and sour aam ka panna, from the tangy nimbu pani to the more mellow bel ki sherbet.

Inside the house, darkened by curtains and screens to keep cool, there was always the musk scent of khus in the air as the screens were watered. Meanwhile, outside the darkened windows, gulmohar trees bloomed, their fiery red colour warning us that we must stay indoors or we would get heat stroke. Once the sun went down, we would emerge from the darkened house and spend the evening playing games in the garden.

Or we would walk to the children’s park at India Gate along a carpet of fallen jamun fruit and thought nothing of coming back and washing our fruit-loot and eating it until our tongues turned furry and a velvety violet in colour. I am sure this ritual died long before Covid could kill it – with increasing public/private bifurcation, much more dirt and pollution and probably tighter parental supervision. This whole jamun loot exercise was conducted under the collusion of the lady who looked after us children and stayed with my parents for 30 years afterwards.

There was one summer ritual we looked forward to more than anything else. It was sleeping out in the garden under mosquito nets. I guess it was all those Enid Blyton books about camping that gave it an air of adventure or maybe it was just the blessed relief of sleeping in the open air and not inside a house that had baked all day in 40 degrees heat. Whatever the reason, the sight of mosquito net kitted charpoys out in the lawn would bring on shrieks of delight. We children would emerge from our evening baths and race each other out into the lawn in our pyjamas, dripping water from our still-wet hair. Then would follow the ritual of talking to each other under the night sky or telling ghost stories in an effort to scare younger and more timid siblings.

The morning sunlight would wake us too early. Walking with our pillows shielding our eyes from the already strong early morning light, we would tumble into the house and try and sneak in a short nap indoors, sometimes succeeding, sometimes not – depending on how vigilant our mother was.

This was many summers ago – India has changed since then. Indians are travelling much more, taking expensive foreign holidays in cooler countries, their children are playing at the Diana memorial playground in Hyde Park and going for boat rides in the Serpentine. And while the world has changed, children have not. It is probably the little dog they make friends with in Hyde Park that our children will remember, not the fact that it happened in London. For years afterwards, they will remember his name, the way his ears flopped and his tail wagged as he came up to them and recognised them from the day before. The lockdown should make us all realise – and some already do – that staycations can be just as rejuvenating as vacations to far away exotic places. They are cheaper, better for the environment and help us appreciate our immediate surroundings more. Because it is the little things that memories – and holidays – are made of!

The writer lives in London and is the author of East or West: An NRI mothers manual on how to bring up desi children overseas.

Advertisement