The vast majority of the Indian public are a silent, non-aggressive, peace loving, non-learning mass of humanity. Since thousands of years, they have been ‘have-nots’ ~ fed on the notion that their present abject condition is due to their karma in their past lives.

With such imbibed axioms deeply etched in their psyche, they never feel dissatisfied. Because of their mental make-up, the vast majority of Indians, do not dream of participating in the unfolding economic opportunities and enjoying the fruits of wealth and its accompanying comforts. They would, rather, unquestioningly accept their lot, for whatever it is worth.

Advertisement

If for a fleeting moment, they feel hurt by their status of “havenots”, a visit to the cinema hall or a quick look at WhatsApp satisfies their urge for wealth and comforts ~ virtual reality! In the last thousand years of our history, India suffered numerous attacks by Central Asian nomadic tribes, Portuguese, French, Dutch and English, which deprived Indians of their wealth, livelihood, education, skills and culture.

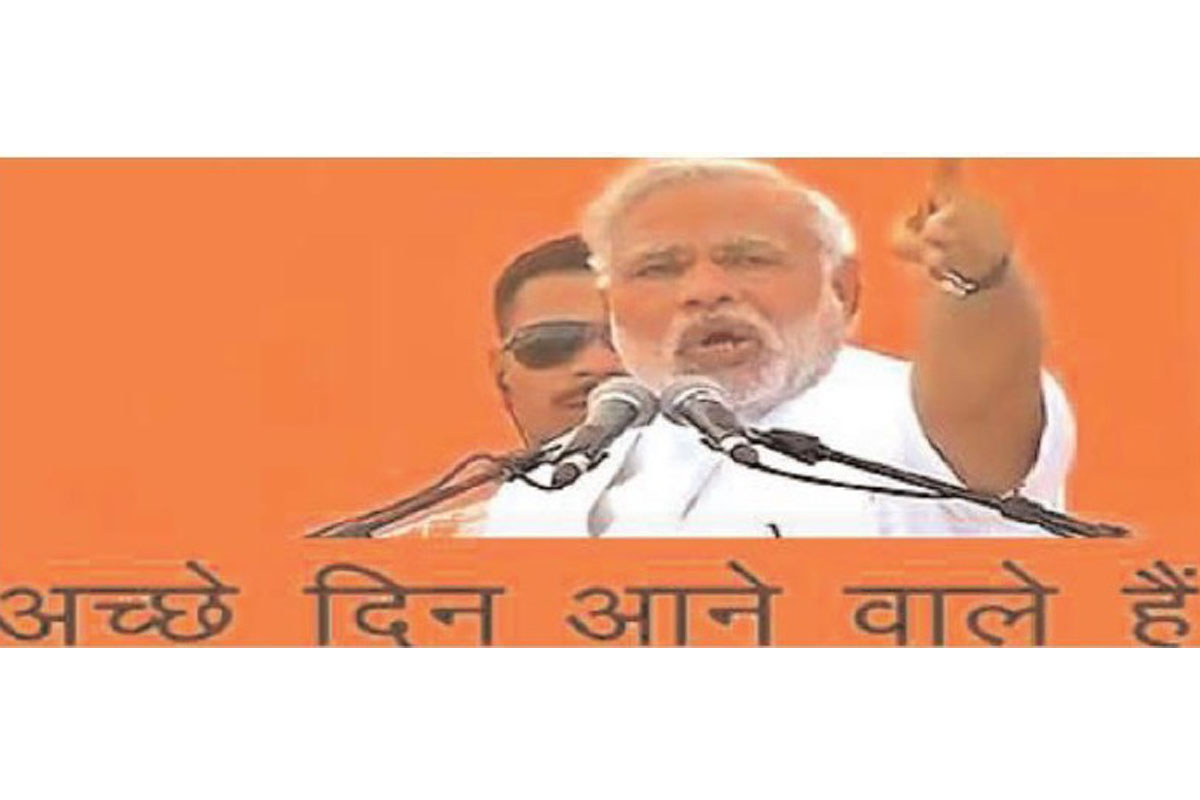

If there was resistance to foreign invaders, it was never supported whole-heartedly by the entire population. Even Gandhi was not supported by the entire country at any time during his long public life. With this background, one can safely conclude that ordinary Indians relish each day as it unfolds with all its pain and suffering, as achche din!”

There is also a section, though a microscopic minority, consisting of the likes of the Ambanis and their satellites, for whom achche din can be forever. A question then arises ~ what is really meant by achche din? How do corruption and black money interfere, if at all, in making achche din a reality for the masses? Before attempting a reply to these questions, let us see what “corruption” means for Indians.

Around a century and quarter ago Lord Acton gave the reason for corruption, as: “Power tends to corrupt and absolute power corrupts absolutely”. The reasons for corruption in India are entirely different because the social conditions of Victorian England were materially different from those in contemporary India.

To understand the genesis of corruption in India, let us first look at how Indian society has organised itself. Our social fabric is made up of various cells, beginning with “self”, immediate family, extended family, caste, religion, region, language. All these cells are institutionalised. A citizen owes his loyalty, allegiance and fidelity fundamentally to these institutions and to systems generated thereunder.

The State or the Government which imply rule of law, calling for a faithful and diligent observance of a maze of laws, rules, orders etc., which we may call collectively as the ‘official system’, gets only our leftover loyalty. Therefore, an individual has very little respect and regard for official systems and is not oriented to follow them.

The two systems, institutional and official, simultaneously operating in Indian society, have created an atmosphere where an individual, from either section ~ ‘haves’ or ‘havenots’ ~ is never ashamed for violating the official system. Corruption in India is a consideration demanded or a price paid for digressing from/ ignoring/ compromising official systems for which there is no social stigma.

Poor/superfluous/ inefficient/ dishonest supervision has fuelled the practice of corruption. The cascading effect of corruption on the economy is immeasurable. One can safely assume that it has a substantial effect on product value. However, the funds involved in such transactions do ultimately find a parking space in the general economy.

“Black money”, which is income that has not been offered for tax, is a misnomer because the same bank notes and bank accounts are used for both ‘black’ and ‘white’ transactions. ‘Black’ money effortlessly gets converted into ‘white’ and vice versa. A small example would suffice. The illegal gratification received by a corrupt politician or bureaucrat is obviously black money, but if it is blown away in a pub (as it mostly is) it becomes legitimate earnings for the publican.

Another example is that of the agricultural sector which is by far the leading employer for Indians and agricultural income which is tax free. Value creation and the contribution of agricultural activities to the economy are grossly under-reported. Perhaps due to illiteracy among farm workers, agricultural activities are not properly accounted for and there is no system of financial reporting of many agricultural activities.

At the end of each crop season, the tax-free money gets mingled in the general economy of the country. There is no accounting or recording of the cash flows from the agrarian sector to the general economy. Cash crops like cotton, oil seeds and sugarcane have telling effects on the cash flows to the markets. Is this money, white or black? Such problems have cropped up whenever planners and economists have tried to estimate the quantum of black money in the Indian economy, consequently, as yet, there is no credible estimate of black money in our economy.

The history of black money is quite short. During WW II and thereafter, the commodities under controlled distribution found their way to the open market and the word “black market” was coined to describe such markets. Again, during British rule, it was considered a nationalist duty to avoid or escape tax payments. Non-payment of taxes, direct and indirect, created a situation where income had to be hidden and not recorded in the accounts.

Thus “black money” was born. The practice of unrecorded income in the manufacturing and service sectors continued after Independence. The official system could not match the ingenuity of the tax evaders either for want of will or nonavailability of resources. These ‘black’ funds have never remained idle. They have been actively utilised in the economy of the country and have generated a large volume of employment in the unorganised sector. Some people have called this phenomenon a “parallel economy”.

The organised sector is also not lily white; black money is the prime mover in the property and jewellery markets, not to mention the political market. Consequently, both the parallel economy and the formal economy were badly affected by demonetisation, which resulted in job losses and a slowdown in the entire economy. With this understanding of corruption and black money, let us examine the meaning of achche din.

For a person belonging to the have-not group, achche din means regular employment, reasonable living quarters, potable water, electricity at an affordable price, opportunity for education of children, and reasonable medical services. In this bucket list, regular employment is of prime importance because regular employment envisages not only engagement but also remuneration commensurate to the cost of living index.

If a person has regular employment he can aspire for the remaining ingredients of achche din. The State can contribute by assuring potable water, providing housing and electricity, and medical services. But can the State generate employment? Is it the duty of the State to generate employment in a free economy? The answer is ‘no.’ The Government cannot generate jobs and it is not the Government’s duty either.

Then how can a society have achche din? By the end of WW II, Germany and Japan were totally razed to the ground. Within five decades, both these countries had regained their lost glory and were recognised as economic powerhouses. How did this happen? Briefly put, the grit, determination and ability to withstand hardships have brought achche din for the Germans and the Japanese. Of course, appropriate fiscal and tax policies also contributed to the speedy development of these economies.

This has a lesson for us, fiscal and tax policies alone will not be enough to bring about achche din. The State will have to play the role of a facilitator by ensuring that all citizens can pursue their vocations and professions peacefully and without interruption. The Government would have to act consciously to help eradicate the corrupt institutional systems prevalent in society and send back religion from the streets to temples, churches and mosques, where it belongs.

The Government can start by deleting caste and religion of individuals from State records. Then, the Government can abjure policies that hamper commerce and industry and withdraw the respectability enjoyed by corrupt elements. Additionally, pro-active trade and taxation policies would also have to be framed.

The bottom line is: Government efforts alone cannot bring achche din, but acting in tandem, progressive policies of the Government, the enterprising nature of our business class and the efforts of our people can definitely bring achche din for us.

(The writers are respectively a Chartered Accountant and a former Principal Chief Commissioner of Income-Tax)