After the grant of permanent commissions to women officers, the next legal battle in progress is about placing them in command of units to enable career progression alongside their male counterparts. In a statement to the apex Court, countering grant of command to women officers, the army stated, “Women may not be suitable for commanding roles in the Indian Army as male troops are not prepared to accept women officers.” The statement added, “The composition of rank and file being male, and predominantly drawn from rural background, with prevailing societal norms, the troops are not yet mentally schooled to accept women officers in command.”

Countering the army claim, the Apex Court bench stated that it was not fair to completely bar women from command posts, as they were doing extremely well. It added, “A change of mindset is required with changing times. You need to give them opportunity and they will serve to the best of their capabilities.” The case is presently sub-judice. This issue came to fore when the army announced permanent commissions for women from April this year in branches other than where they were already serving on a permanent basis. New branches where women would now be granted permanent commission included Engineers, Signals, Aviation, Air Defence, Electronics and Mechanical Engineers, Army Service Corps, Ordnance and Intelligence.

Advertisement

They are still barred from serving in combat arms including Infantry, Mechanized infantry, Armoured Corps and Artillery. Critics of the army’s refusal to induct women in combat roles cite Western nations and claim that if they can induct women into combat roles, so can the Indian army. Western nations induct women in every arm or service to cater for shortfall in male recruitment. However, most serve in non-combat duties. The Centre for Military Readiness of the US, stated in an article on 1 April 2013, “Since the attack on America on September 11, 2001, a total of 149 women deployed in Afghanistan, Iraq, Kuwait, and Syria have lost their lives in service.”

It adds, “Most servicewomen were killed by improvised explosive devices (IEDs), and some died in military plane crashes.” It implies that casualties due to live combat were extremely rare. It also quoted data from earlier conflicts to say “7,000 women served in Vietnam, of which 16 were killed, most nurses. In the first Persian Gulf War, 33,000 women were deployed, 6 perished due to scud missile explosions or accidents.” Globally, women are kept away from active combat. The Indian Army’s logic for excluding women from command has sparked a debate. Many have disputed the army’s logic claiming patriarchy remains widely prevalent in the organisation and the army’s view is biased.

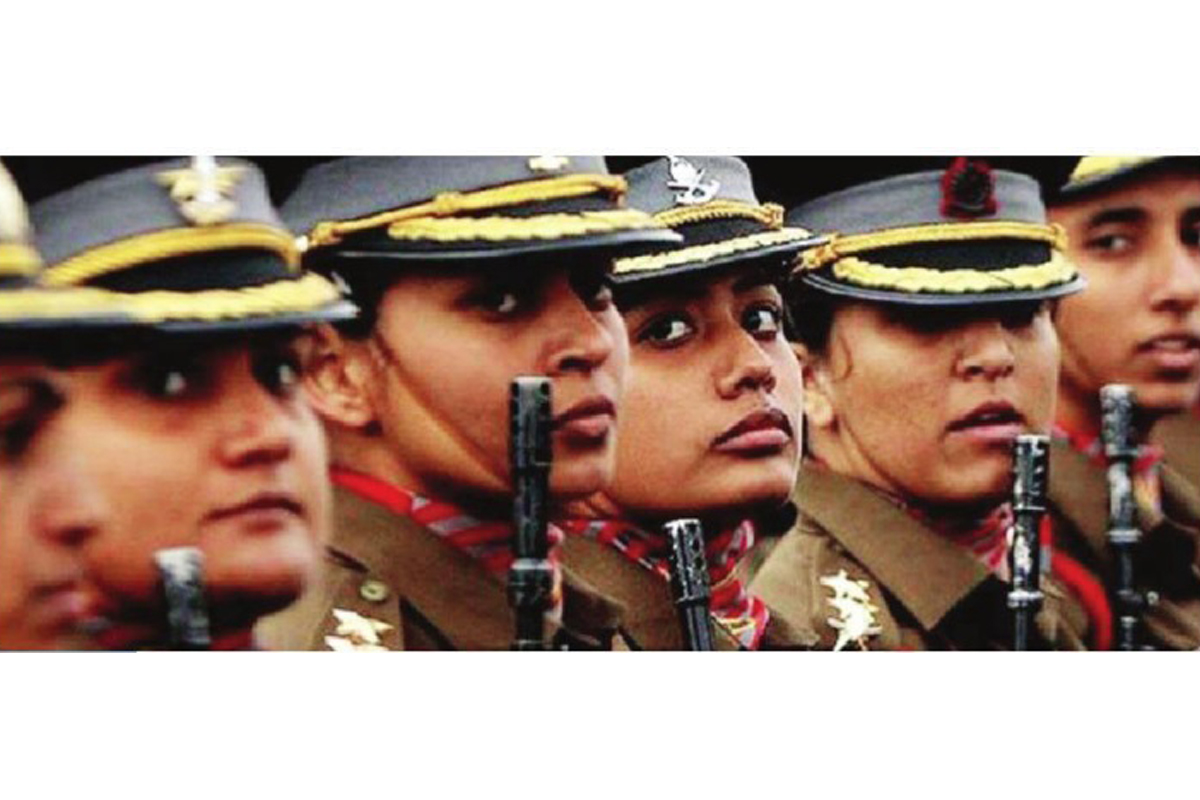

There is no doubt that women officers have proved themselves as assets wherever they have served. There are multiple reasons why the Indian army hesitates to place women in command of even service units. In Western nations almost every unit has a mix of men and women at all levels. Thus, for a woman to command is natural, since both sexes serve together. Even in the corporate world, men and women work together and hence a woman at the helm is natural. In India, the army has just begun inducting women in lower ranks. The first batch of approximately 120 women in the military police are undergoing post-induction training at Bengaluru.

Presently, the rank and file of all units is exclusively male. Once women are inducted in other branches of the army at lower ranks, the environment would undergo a change, and command of units by women would be a natural flow. Protection of women is natural in Indian society and under no circumstances would the army post them to command even service units in areas of active hostilities or those that are terrorist prone. This implies that if they were to be given command, it would be in peace.

This further implies that some locations would be blocked for those who are genuinely due for a turnover, adding to discomfort within the cadre. While the Indian officer cadre comes from cities and is well groomed, the men are traditionally from rural backgrounds. There is a variation in culture between urban and rural India. Women in rural India are expected to be homemakers. They are respected, protected and kept away from danger. In most regions they are not permitted to even venture out alone. It is the opposite of cities where women, apart from being better educated also possess greater freedom. It is from this village culture that the Indian jawan emerges.

Hence, to accept open criticism, which is natural in command scenarios, or obey orders without questioning from a woman, one who may be the only female in a male-dominated bastion may, not be easily acceptable in the current environment, especially when the jawan’s traditional view on women is different. This culture must be changed prior to grant of command to women. Apart from units, the army has proposed NCC and Sainik Schools as alternate avenues for command by woman officers, while it works on its internal culture. Others which can be included are Military Engineering Service command appointments and Wireless Experimental Units.

However, amendments need to be made to existing orders to ensure further promotion for women after these commands. Alternatively, staff streams could be considered for women to progress further in service. In the meanwhile, the army has commenced posting women officers to training centres, where recruits are inducted from civil society and trained to become soldiers. Thus, from his first day in the army, the young recruit observes a women officer as his superior, instructor and mentor.

Slowly, his perception changes, and he begins to accept orders, criticism and guidance from women officers. This is a logical approach adopted by the army, which will, with passage of time bring about a changed internal culture. The army should have stated in court that suddenly changing existing norms may not be the right approach. There needs to be a cultural shift within the system to ensure change is accepted. Till then, it may be premature to place women in command.

(The writer is a retired Major-General of the Indian Army)