Sonakshi Sinha slams Mukesh Khanna for blaming her father over Ramayana blunder

Sonakshi Sinha responds to Mukesh Khanna's criticism over her Ramayana question on KBC, defending her upbringing and urging him to move on from the incident.

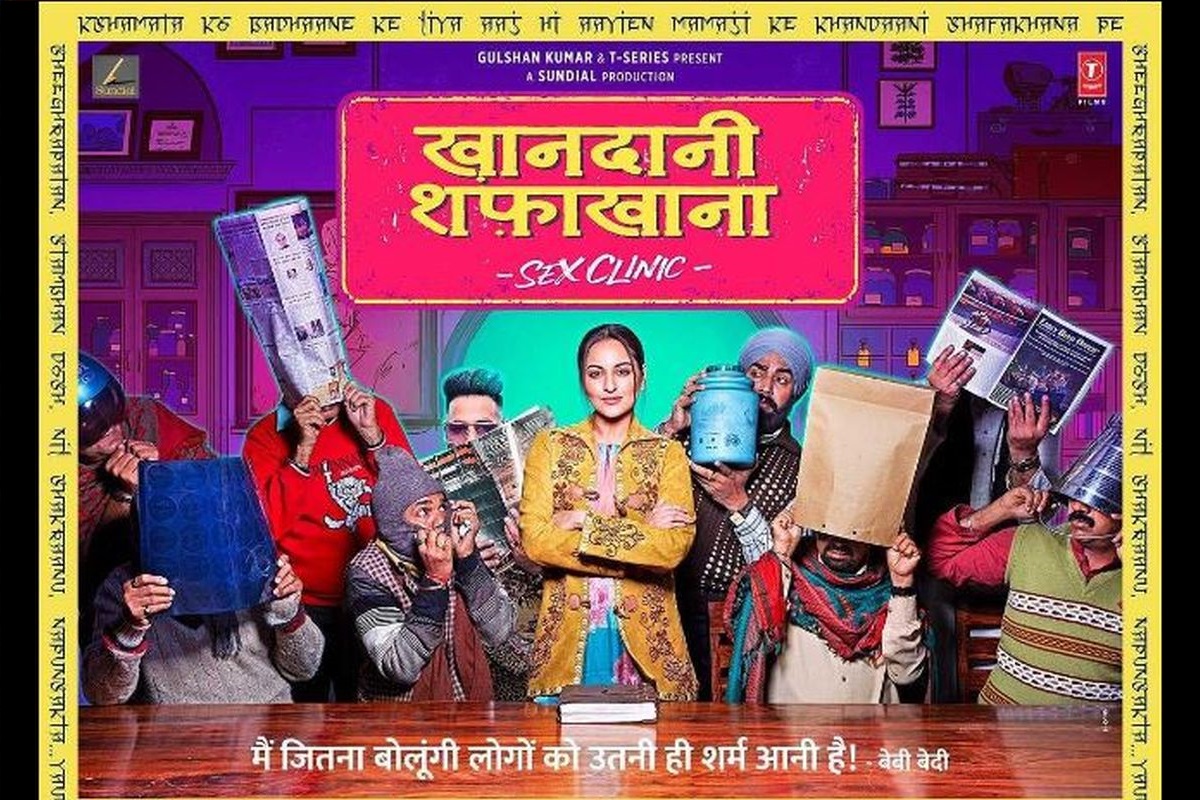

Khandaani Shafakhana carefully plays with the old-school mainstream masala entertainment genre. It inverts major tropes and lends a fresh perspective to romance, family vibes and values, men and yet falls prey to some invisible notion of order.

( Photo: IMDb)

Film: Khandaani Shafakhana

Cast: Sonakshi Sinha,Varun Sharma, Annu Kapoor, Badshah, Priyanshu Jora

Advertisement

Director: Shilpi Dasgupta

Advertisement

Khandaani Shafakhana is a brave fairytale. A film made with an intent to be a family entertainer, it does two revolutionary things. One, it addresses a subject – sex that our society is coy about talking and second, explore the narrative through the lens of a female gaze. Not just the gaze of Sonakshi Sinha, who plays the lead character in the film, but also that of the woman director – Shilpi Dasgupta who has attempted her first directorial feature with Khandaani Shafakhana.

The film opens with a rush to establish the central lead, Sonakshi Sinha’s backstory, why she is the way she is or the way she wants to be but then proceeds chronologically to establish the dramatic arch of the narrative that obviously has two cathartic moments – One, before the film closes for the first half and second at the end of the film.

The Rajkumar Hirani model of filmmaking is finding its true disciplines in filmmakers who are keen on exploring social stigmas and taboos around them through the genre of comedy and drama. However, it would be unfair to generalise their work, since perspective plays the differing factor for all.

Shilpi Dasgupta’s film is very well-written, not just in terms of dialogue but also in terms of the screenplay arch of the conventional Hindi film masala entertainer. Each scene is established and so are the characters in it. There are no extras, and the economy of using characters, situations, production-design and most of all the music, to further the narrative of a film that is trying hard to make sex a living-room conversation are all praiseworthy efforts. An effort perhaps, that has been giving space to small films to leave a mark, precedent examples being Badhaai Ho.

But, setting up a film in a small-town like Hoshiarpur, Punjab does demand a couple of explanations. First is, how important is the role of aestheticism in cinema of a certain kind and how far removed should the sensibility of the actor or maker, writer be when they are trying to embody/bring the text into life onscreen.

Khandaani Shafakhana is set in a small town and follows the story of Baby Bedi (Sonakshi Sinha) as she hurdles through society, relatives and economic concerns to run a sex clinic that she inherits from her deceased uncle, ‘Mamaji’ (played by Kulbhushan Kharbanda). Firstly, the production design used mostly well to enhance and contribute to the tone of the film, sometimes forgets that indulging too much into vintage nostalgia can go overboard and make the economics of the text or the characters’ middle-class upbringing questionable, however small may that be.

If Sonakshi Sinha is frowning for most part of the film to establish that she does not understand the dualities of a society or dealing with her mental demons alone in bathrooms, she also is playing a character of a woman who is the product of a society that does not talk about sex. She does hit the right note here and there and goes overboard sometimes when not required, but clearing your throat to speak when there is uncomfortable silence is not a feature that translates to the general psyche of expression used by indigenous characters in our films. That is a bookish notion, which does not technically belong to the people the film is dealing with.

In that part, the writer’s sensibility sneaks into the narrative as it does in places where lectures on sex-education are delivered by people here and there.

Despite that, Sonakshi Sinha’s character for a change has been carefully chalked out. The portrayal of psychological complexities may not be Sonakshi’s strength but small and quiet efforts to deliver the theme of the moment and to not play that outright-out there-conventional-model of an empowered woman, that has become the sole interpretation of a liberal-modern woman in Bollywood, is again commendable.

Apart from Sonakshi, there is Varun Sharma who plays a ‘ladla’ brother/son of the household with no sense of responsibility. A character, important to portray on screen and establish that the ‘beta’ of Hindi cinema can be lethargic, and not always the shining exemplar of Atlas – holding the mountain of responsibility on his head. For a change, it was great to see a man whining on the silver screen to be married. It was for small moments like this that made Khandaani Shafakhana a very new film, in terms of its treatment. In fact, it is Varun Sharma’s character that stays with you even as the film ends.

Annu Kapoor’s sex-education class continues from Vicky Donor and goes onto this film; only here he plays a lawyer instead of the doctor.

Rapper Badshah who makes his debut with the film, plays himself. A Punjabi singer with a massive fan following across the state. His performance in moments of immense emotional intensity is bland but when the film is on track, he plays himself well.

Another commendable mention in the film is its background score. Especially of sequences when the heightened tension of Sonakshi Sinha’s mental state is portrayed through the literal music soundtrack, if one may call it. For instance, when Baby Bedi is taken for the first time to the clinic, the ‘predatoriness’ of the fellow marketers in the complex is underscored with a track embossed in eagle sounds.

The romantic angle of the film was introduced with Lemon hero, played well by Priyanshu Jora. Jora is more like the voice of reason for an otherwise dazed and confused Baby Bedi. He plays the mind of the film, while Baby plays the heart of it. Though his sudden entrance though chronologically correct, is unexplained in the post-interval film; it was welcome for all the reasons that one watches a masala entertainer-paisa vasool film.

In the post-interval film, when Khandaani Shafakhana begins to feel like a fairytale, some real struggles that a middle-class woman and her family would face come to fore, and save the text from sinking into nothingness. The reunion and catharsis which occurs in courtroom dramas as in all old-school Hindi films where a family reunites with their courageous breed and the moment of realization sinks upon them that their kid was always right in the back of their heart, is there in this film as well.

The film carefully plays with the old-school mainstream masala entertainment genre. It inverts major tropes and lends a fresh perspective to romance, family vibes and values, men and yet falls prey to some invisible notion of order.

Like Andrei Tarkovsky said in Sculpting in Time, “… That sort of fussily correct way of linking events usually involves arbitrarily forcing them into sequence in obedience to some abstract notion of order. And even when this is not so, even when the plot is governed by the characters, one finds that the links which hold it together rest on a facile interpretation of life’s complexities.”

Sometimes, one wonders if these notions of conforming to linearity, in a restrained style, almost in the tone of reporting events and deducing the obvious social message are the sole motives of the filmmakers. Is the plot and the form then just a garment to state the message in the most engaging way? Or is this the only reason why these small films make a mark for a fraction of time and then dissolve into everything as daily and normal as the everyday? As we fail to register the normalities of our life, so do we fail to acknowledge the message that these films wish to deliver.

Rating: 2.5

Advertisement