Academia urges strong linkages with industry

Sustainable and inclusive education is essential for enhancing the future well-being of both communities and nations.

However, one cannot ignore the excellent idea called the National Commission Network which not only makes knowledge sharing easier and richer but offers solutions to infrastructural problems.

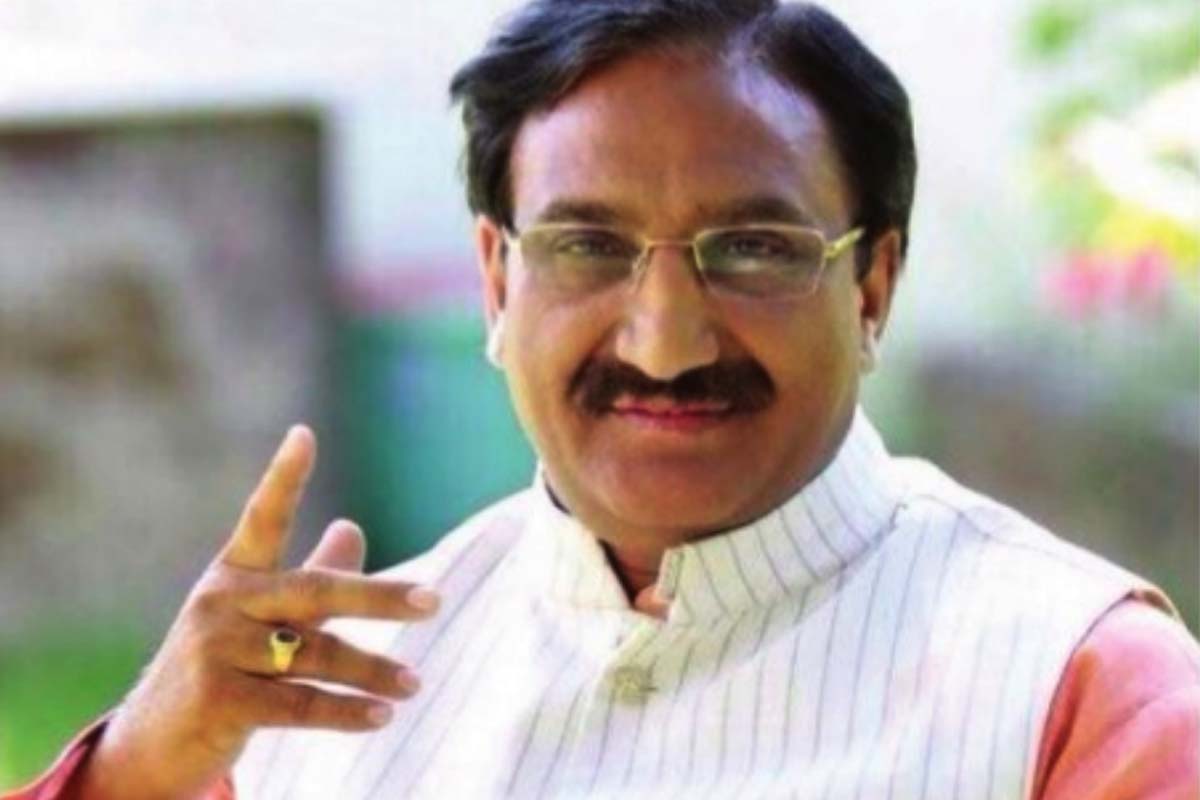

PHOTO: STATESMAN NEWS SERVICE

Prakash Javadekar as HRD minister made promises galore, but in the midst of ”little-done-and -undone vast”, India is looking forward to being a nation with a new look national education policy, with a new minister Ramesh Pokhriyal to transform hopes and aspirations into beliefs accompanied by a strong sense of determination to convert them into reality.

Admittedly, India has experienced an unexpected boom in educational opportunities in the last few years, and access to schooling as also to higher education has significantly improved. But sadly, the whole primary education system plagued by rampant absenteeism is in shambles, with little to monitor, guide or control. It is almost on the brink of decay with village panchayats bent on using schools for the furtherance of their political ends

The latest 2017-18 Performance Grading Index reports of all states and union territories in school education published by the human resource ministry, which contains five heads for assessment — learning outcomes and quality, access, infrastructure and facilities, equity, and governance processes — reveals that the country as a whole has been slipping down the school education ladder for quite some time.

Advertisement

True, Right to Education Act, 2009 has established free and compulsory education between the ages of six and 14 as a right. But surveys indicate that compliance with the RTE Act is poor. Each school should have one trained teacher per 30 students at the primary level, but the fact that 10 lakh posts remain unfilled in government schools highlights the decay. There was hardly any thrust from the government to ensure compliance. The date for implementing all the provisions in the Act was extended to March 2019. Funds for the Sarva Shiksha Abhiyan and the Midday Meal schemes remain static. It is time for the new minister to act. It is discouraging that the school curriculum guidelines of the NCERT have not been restructured for nearly 14 years. Infrastructure is still far from ideal. Teachers’ appointments, training, accountability, incentives etc. need to be reviewed. The new minister must be reminded that the 2005 guidelines had laid stress on “learning without burden”, as interpreted by Prakash Javadekar as lightening the burden by pruning the syllabus.

The Kothari Commission in 1966 had recommended increase in expenditure on education to 6 per cent of the GDP. The Report of the Education Commission 1964-66, unequivocally stated that “if education is to develop adequately, educational expenditure in the next 20 years should rise from Rs 12 per capita in 1965-66 to Rs 54 in 1985-86”.lt has been lamented that while Brazil spends 5.9 per cent of its GDP on education, Russia 4.1 per cent, China 4 per cent and South Africa 6 per cent, India lags behind with 3.8 per cent of its GDP being used for education. To maintain uniform standards which the RTE legislation envisages, a common schooling system as followed in Britain is sought. In Indian perspective a common schooling system will require a ban on all private schools – a violation of the fundamental constitutional right to practise trade and enterprise.

Recently, the UGC and the HRD ministry tightened purse strings and replaced the usual system of grants of funds with loans for infrastructure development in public institutions. Indian higher education already suffers from a massive faculty crunch, and it is certain that hiring quality teachers for our much sought -after “world class“ universities will prove a challenge before the new minister. It is nice to aim at excellence, but unlike the proliferation of business schools, a world class Institute cannot be established in haste. Already a high-level committee by the HRD ministry has lambasted the chaotic expansion in higher education and suggested the formation of a single apex body instead of regulatory bodies like the UGC, AICTE and MCI. It has also suggested that the government should interfere less in academic and administrative matters. It seems that educational institutions in India have been plagued by the perquisites of the Nehruvian state that guaranteed an endless flow of taxpayers’ money without any accountability for the quality of teaching and research conducted. Reforms in higher education like the proposed restructuring of the UGC, autonomy for major institutions, thrust on outcomebased learning, increase in size of medical education, establishing national testing agency might be some of the radical steps towards enhancing the quality of education without putting a sizeable burden on government exchequer.

There has been, lately, serious curtailment of research funding for non-premier research institutes. It is feared that many innovative ideas may never see the light of the day if the situation continues. Also, the ability of most Indian institutions of higher education is sometimes blunted due to limited flexibility in their decision making process, particularly in regard to governance issues. This area should be taken into serious consideration. In practice, to meet the demand for job-oriented education, public universities and institutions must be let loose. It may be mentioned that instead of encouraging the role of private sector to contribute to higher education, the public policy hitherto does not look to be friendly.

In view of Indian universities drawing a blank regarding top 100 educational institutions of the world list, it is time to consider that if we aim at dominating the global discourse, we need universities that not only create skilled human resource but also encourage indigenous research and development and instill scientific thinking among the people. Focus must be on research in order to develop strategies and mechanisms for effective application of knowledge to specific national and local needs. It may be noted that despite government allowing 100 per cent in FDI in education sector, it has not experienced much success. We have been in the process of encouraging FDI not only in the development sectors, but in retail segment as well in order to enhance foreign funds with incidental advantage of technology transfer, job opportunities and benefits to domestic firms and consumers. But since education is not a tradable commodity, the implications of FDI in the higher education sector call for reflection. In fact, more focus should be put on exploring the possibility of Public Private Partnership model to provide more access to qualitative higher education.

The higher education system in our country needs to overcome many challenges to be at par with global campuses. Our Gross Enrollment Ratio (GER) is at 25.8 per cent which stands far below the global average of 27 per cent. India expects to have the largest number of college-going youth by 2030 and to accommodate this huge influx of pupils we will require a huge number of colleges and universities. The draft education policy has opted for Four Years Degree Program (FYDP) which would further require more accommodation. The new minister must think seriously about this.

On the recommendations of the National Knowledge Commission, a National Skill Development Mission was set up with its aim to provide training in myriad skills – from hospitality, cooking, nursing and Indian language skills to plumbing and fixing electrical appliances and motor vehicles – to 10 million people every year. At a meeting of the Reconstituted Central Advisory Board of Education several members criticized the NKC and asked the government to reject its recommendations.

However, one cannot ignore the excellent idea called the National Commission Network which not only makes knowledge sharing easier and richer but offers solutions to infrastructural problems. Indian schools, colleges and institutions of higher learning are to be linked with one another and with the rest of the globe more efficiently. Bringing backward areas into the map of quality education is a task that will require both sensitivity and restraint on the part of the new minister,

Advertisement