Unfinished Agenda

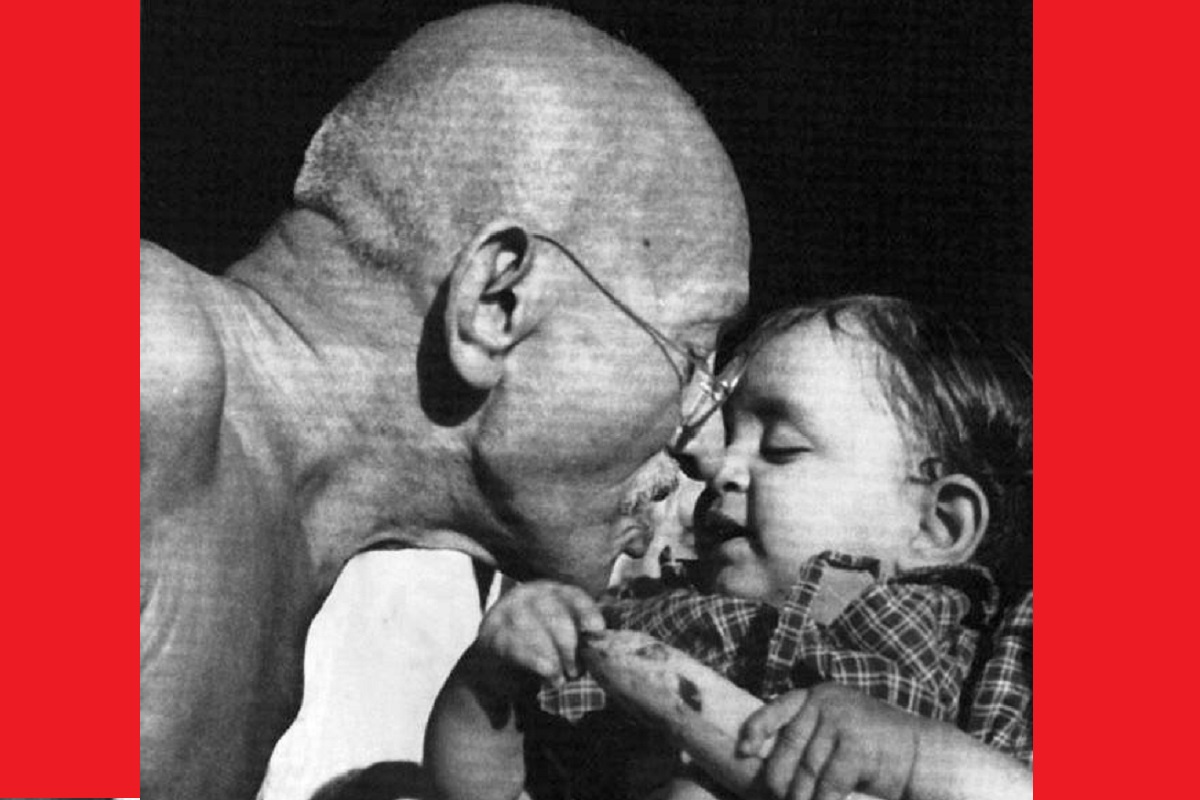

Mahatma Gandhi, the greatest man of the twentieth century, often talked about poverty. For the prophet of non-violence, poverty was the worst form of violence.

In formulating his doctrine of trusteeship, Gandhi was profoundly influenced by John Ruskin’s Unto This Last and Other Essays. He was so impressed that he later translated the book into Gujarati with the title Sarvadaya.

The Gandhian theory of trusteeship departs significantly from Marxian economic philosophy. (Image: Facebook/@FatherofNation)

‘Consciously, or unconsciously, every one of us does render some service or another. If we cultivate the habit of doing this service deliberately, our desire for service will steadily grow stronger, and will make not only for our happiness, but that of the world at large.’ ~ Mahatma Gandhi

Psychologist David Mc- Clelland of Harvard University had once conducted an interesting study in which he showed to students a film of Mother Teresa caring for the sick.

IgA levels (IgA is an antibody in the saliva which affords protection against colds and other respiratory infections) of all participating students were measured before and after the film. Interestingly, the levels of all students had increased, irrespective of whether they liked or disliked Mother Teresa. The study indicates that in spite of our superficial beliefs, our deeper consciousness seems to be predisposed to tender, loving care, and we respond to it even when we are only a distant, observing third party.

Advertisement

Another psychologist, Shelly Taylor, also established the fact that tending and caring for others originates from deep within our social nature. Mahatma Gandhi believed that human beings representing ‘soul-body composites’ are revelations of two important values of ‘self-interests’ and ‘social affections’. While the former is critical for one’s existence, the second is for ‘the concern for others’. He argued that a creative combination consolidates the foundation of an economy ensuring ‘capabilities’ and ‘freedom’.

Gandhi did not seek ownership of wealth, property or titles, but rather stewardship. In his words: ‘Relationship is the oxygen of life, Trusteeship is calculated to promote relationship.’ Gandhi’s notion of trusteeship seems to be theological. However, in pursuing his argument, he came closer to St. Thomas Aquinas and founded his religious belief that everything belonged to God and was from God. In his early life, Gandhi nurtured various kinds of beliefs drawn from old customs and religious traditions.

It was his firm faith in the basic goodness of man that led him to evolve the trusteeship doctrine. He drew on indigenous sources while formulating his notion of trusteeship. Two fundamental concepts of the Bhagvad Gita, namely aparigraha (non-possession) and samabhavana (equality or oneness with all) were critical in his formulation. The Bhagvad Gita also makes an important suggestion ~ “Enjoy thy wealth by renouncing it.’ In formulating his doctrine of trusteeship, Gandhi was profoundly influenced by John Ruskin’s Unto This Last and Other Essays.

When Gandhi was in South Africa, to sort out some problems relating to the publication of the weekly magazine, Indian Opinion, he paid a visit to Durban in October 1904. Henry S L Polak saw him off at the station and gave him a book containing merely 80 pages entitled Unto This Last and urged him to read it during the 24-hour journey to Durban. It was late evening, but before going to sleep Gandhi began reading the book. He did not put it down until he had finished it. The book indeed seemed to have cast ‘a magic spell’ on Gandhi. He summarised the teachings and the most important of these was: ‘that the good of the individual is contained in the good of all.’

He was so impressed that he later translated Unto The Last and Other Essays into Gujarati with the title Sarvadaya. According to Gandhi, Ruskin laid the foundation for trusteeship. Gandhi believed that trusteeship was the only sphere on which he could work out a perfect combination of economic equality and morals. For an inclusive society, the common man should trust his trustee and the latter plays the role of a custodian. However, in concrete form, the trusteeship formula has several aspects. (1) It is based on the faith that human nature is never beyond redemption; (2) It provides a means of transforming the present capitalist order of society into an egalitarian one.

It has no place for capitalism, but gives the owning class a chance to reform itself; (3) It does not recognise any right of private ownership of property except so far as it may be permitted by society for its own welfare; (4) It does not exclude legislation on the ownership of wealth; (5) Under the state regulated trusteeship, an individual will not be free to hold or use his wealth for selfish satisfaction in disregard to the interest of society. And (6) under the Gandhian economic order, the character of production will be determined by the social necessity and not by greed.

The Gandhian theory of trusteeship departs significantly from Marxian economic philosophy. He repeatedly opposed the idea of expropriating wealth or property from the rich. Paradoxically, for Gandhi, the wealth did not ‘belong ‘ to the rich owner, the so-called owner was merely the ‘trustee’. Marxian socialism aims at the destruction of the class called capitalists. Gandhian socialism, being ethical, is different from Marxian socialism. If Marxism is the child of the Industrial Revolution, Gandhian theory can be understood only in the context of certain basic spiritual values of the Indian tradition. Moreover, Gandhi was a lawyer in England.

As an Inner Temple barrister, he was doubtless acquainted with the concept in English common law surrounding trusteeship. Trusteeship is often referred to as ‘one of the glories of English Common law.’ Gandhi was confident of the success of his doctrine of trusteeship for two important reasons: (1) it has the sanction of philosophy and religion behind it; (2) absolute trusteeship is an abstraction like Euclid’s definition of a point and is equally attainable. It is basically a mental construct, drawn on strong moral values.

To translate trusteeship into reality, Gandhi was not hesitant to deviate from his well-avowed path of non-violence. Approving violence he argued: ‘I would be happy indeed if the people concerned behaved as trustees, but if they fail, I believe we shall have to deprive them of their possessions through State with minimum exercise of violence.’ Trusteeship cannot be understood merely with reference to the ethical roots, it has to be located in the overall structure of Gandhian politics that had its roots in the contemporary socioeconomic and political milieu.

The Mahatma visualised an inherent sacredness to the natural world, to the biosphere. He also realised that there is an intrinsic value to nature and its animals and plants. We as human beings use and consume soil, water, plants and animals. But as trustees, it becomes necessary for us to use them in such a way that does not abuse them, lead to waste or diminish it for future generations. At present, economic growth, based on over-exploitation of nature, has become the be-all and end-all, and it is seen as the panacea for all our ills.

Ecologists, environmentalists and many scientists unanimously agree that our economic activity is ecologically unsustainable. The time has come to consider ourselves as trustees. Trusteeship has another important aspect. Gandhi believed that the concept was not a permanent social arrangement, but a stepping-stone to something higher. He believed that through appropriate non-violent measures, the rich man could be made to hold his property as a trust that could later be utilised as a national asset. During his long years of struggle, Gandhi showed how winning the heart of the opponent, arousing his sense of fair play and creating a favourable public opinion could contribute to the building up of circumstances favourable to a powerful movement.

Although Jawaharlal Nehru preferred ‘state-directed planned development’ by agreeing not to disturb the indigenous business houses, he, at least in the initial years of his rule, appeared to have endorsed the spirit of trusteeship. As regards national industries, the concerns of the Congress leaders, including Nehru, Subhas Chandra Bose, among others, were not substantially different from that of Gandhi. After Independence, Acharya Vinoba Bhave’s Gramdan was a significant step in the direction of ‘trusteeship’.

The movement, according to Prof. D R Gadgil, ‘is an unprecedented movement with many and complex implications and very great potentialities.’ Louis Fischer has described it as ‘the most creative thought coming out of the East.’ Trusteeship set a powerful trend in India’s development trajectory that was articulated differently in different phases of history. The concept is manifest in our cooperative policies, the community development projects, the taxation policy and in Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR). Trusteeship is Gandhi’s effort aimed at ‘spiritualising economics’ which is based on ‘trust’. ‘True economics’, he said, ‘stands for social justice; it promotes the good of all equally including the weakest and is indispensable for decent life.’

(The writer is a retired IAS officer)

Advertisement