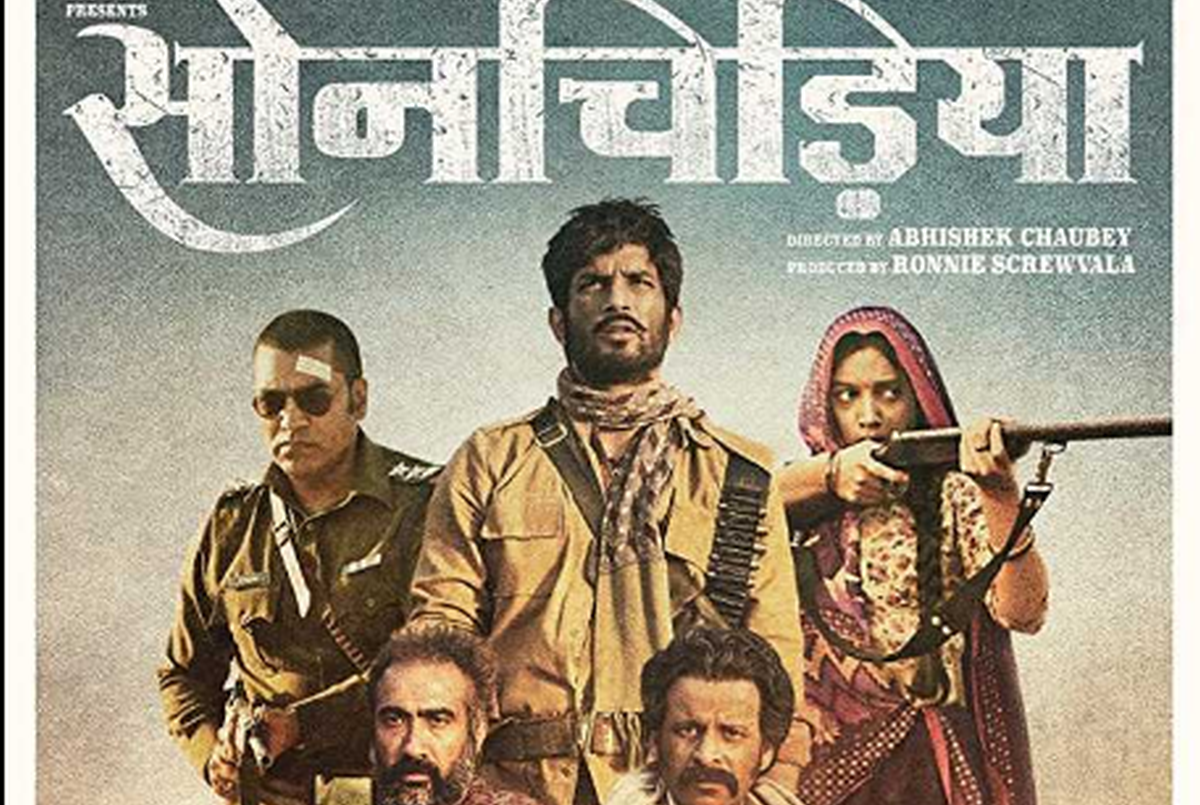

Film: Sonchiriya

Director: Abhishek Chaubey

Cast: Sushant Singh Rajput, Bhumi Pednekar, Manoj Bajpayee, Ranvir Shorey, Ashutosh Rana

Rating: 3

Even though I hate to admit it, the film feels like a Mad Max Fury Road; only it’s without the cars and trucks, and the genre is not dystopian. The sandy dunes ( beehad) will remind you of the former film. But more so because, the idea of deliverance and existentialism run parallel in both films.

But there is a lot of depth to the film, so much so, its mind boggling to keep track of the dichotomies that Abhishek Chaubhey has addressed in the film.

To go by the film chronologically, the opening sequence reminds us of Udta Punjab, the slow opening, long shot and close-ups, in introducing the characters, a band of rebels, I would not like to use the word dacoit, as Sushant Singh Rajput says that they escaped the goodness of the world to become rebels-dacoits. There is a very thin line in the narrative between the two.

But that does not mean that I am forgetting the setting of the film.

It is based on the infamous dacoits of Chambal who have considerable portion of cinema dedicated to them and this comes from someone who still has not seen the Bandit Queen.

Yet, the introduction is from a genteel distance. The background shot, gives access to the character’s but never directly introduces them; is perhaps, a move to puncture the typical tradition of introduction of heroes or even just the motive of the director to bring to attention a theme in the film- Curse; a burden and the idea of “Sadgati”.

In fact, in the first half of the film, there is a lot of focus on still action. With films around the world experimenting with live action, by even using still photography in the cinematic medium, I felt this was new.

There is a certain slowness in rolling out of the film, sometimes necessary but later becomes an extra second on the movie time, that could easily have been cut, especially in the first half. The post interval film was too filled up.

While the film kept venerating the figure of Man Singh aka Dadda (Manoj Vajpayee), the puncture in the narrative with his ___ in the first half was classic. His presence was looming in the entire film, but the move to get rid of the undying typical hero was subtle. In fact, there is no figure of a typical hero throughout the film. All of them are swinging between the old school machismo and the modern vulnerable, more real sense of Hindi film heroes these days. Even Ranvir Shorey, who is the closest to the “Angry Young Man”, hero does not fall into that category.

The introduction of the small girl, whose curse Manoj Bajpayee and Sushant Singh Rajput carry on their heads throughout the film was also unique. Initially, it came across as a glimpse into the latter’s psyche but when Dadda also accepts seeing the girl that no one apart from the two can see,we realise that the characters are more closely connected. It becomes clear, later in the film as to what the curse is. But both, Bajpayee and Rajput play ideals to reach. They are the same vortex of an ideal pole.

Both play their characters well. I felt Manoj Bajpayee was more distanced from his character, as if just observing the life around him, reacting but never in the typical-expected sense of a gang leader. It was a very distant, take; very different. Sushant, on the other hand, was more involved, perhaps the existentialist struggle he faces required him to be, but we never have complete access , close-up shots( apart from 1 or 2 here and there) of him either.

Every time the narrative built up on one side, there was always a way to puncture it. In the middle of the first encounter with the police, in the medley of hyperbolic filmy music and action, a simple scene between Sushant Singh Rajput and a man who stops him is an example. When the man asks a question rather simple whether he (Lakhna) is a policeman or a dacoit. It felt banal and extra, too simple in a scene that was on its way of achieving heightened glory.

As the narrative of the film progresses, time and again, the camera moves away from the action, giving us a series of long overhead shots; distancing itself from the action down below. A break that the makers feel is necessary, a shot of breath before it plunges back into the ravines — this happens less in the second half, perhaps because involvement is more in the text there.

When Bajpayee sees the girl child during the wedding-party-encounter, the camera comes really close to his face, yet revealing everything to almost nothing in the next second. A similar scene is repeated in the last encounter of the film. This is perhaps one of the very few times we get a really close exposition into the character’s state of mind. The girl’s appearance becomes clearer only in the second half.

The use of music is interesting. It is used as a major narrative-explainer and furthering tool. Where a bullet shot begins the song, Baagi Re, another bullet ends the song. There is in fact a lot of noise in the film, though one also gets to see a lot of silence in this genre — silence complimented by music most of the times. In fact, most scenes of the film which involve conflict and intimacy are portrayed with only the background score. The dialogues of the film express the state of minds of the characters, their conflicts within themselves and with their gangs- only a furthering of the story to make it more comprehensible. This was something very new. For mostly, to express one’s psychological state, music performs an easier task of connecting, and I have always seen conflict and intimacy amply filled with dialogue.

Even the introduction of Bhumi Pednekar was classic in the film. The movement of a fluid, shadow which is hers’, a character introduction always from the back; never giving direct access to the characters is something that Chaubey has played around a lot in the film. It is perhaps only her, who introduces herself in the “Naam hai Shehenshah” style.

“Indumati Tomar naam hai mera.”

In other words, she really is the only typical Hindi film hero, her character trajectory runs like that- fights evil, struggles, and then emerges a glorious saviour, literally in the film and metaphorically in terms of the Hero-character arch.

The metaphor of running is really apparent in the film, perhaps, a continuation from Udta Punjab, with shots of feet and ground always in move, or rebels running, police running, and Bhumi running.

The dialogue of the film, though sometimes incomprehensible; the dialect went too far sometimes, is great. It is witty and catchy. It is also poetical.

Dialogues such as “ Khoon ke badle Khoon”

“ ye baat parivaar ki nahi, insaaf ki hai”

“sarkari goli se mare hai kya koi…. Inke vaadon se…. Bhaiyobeheno”

“ Ye ghero ghero nahi, chakravyuh hai”

To begin with the philosophical themes in the film, the question of a rebel’s dharma is very important. The answer to which Sushant keeps seeking from the leader Dadda and later Vakil Singh (Ranvir Shorey). It is not so much about dharma itself, but more about loyalty to a cause that no longer gives satisfaction, to a break away from it. The poem about the food chain that in the larger context also signifies characters eating each other (metaphorically) lies at the heart of the film.

My most favourite were the two policemen, also Thakurs, who in this field of caste war politics are like the voice of God throughout the film. They deliver the final justice in the film (very Mahabharatian). It is through them that the theme-of how a mouse is eaten by a snake, a snake by a vulture and that is the law of nature- which is the long and short, plot of the film, finds closure. They make these philosophical remarks a couple of times in the film, reminding us that the gang wars are only a premise, the film wants to talk about something else too.

The idea of seeking deliverance becomes apparent in the second half of the film. It begins with Rekha Bhardwaj’s song Sonchiriya, and we are later told the significance of the name. Ranvir Shorey towards the end of the film spells it out more clearly. It is an ideal that we all chase, and yet never achieve. Its’ everyone’s struggle out there to seek deliverance in some form, whether from their living circumstances; which is the behead/ravines and the life that the dacoits lead to a possibility that a surrender to the police might work as a Duex-ex-Machina. This conflict, in personification is given to Sushant Singh Rajput, who does considerable justice to it.

Shorey’s dialogue that Man Singh found his deliverance and that they (Vakil and Lakhna) had their chance when the ideal walked into their lives in the form of an innocent girl, who needs a saviour, is the literal call for deliverance. It was a perfect “tell, not show moment”.

Another height of the film in the second half is the catharsis given to Phuliya Devi (Phoolan Devi) who avenges her enemy, in a scene of conflict again where her screams of anger and anguish are the only music to the scene. The scene is never shown. All you can see is the reaction of her gang, Sushant, his friend and Bhumi Pednekar. Everyone is looking for release in the film, a release of mental exertion from their vigorous lives in the form of physical martyrdom. That, which they all understand as Deliverance; a prominent theme of the film.

Another dichotomy that is played around with is that of Revenge and Justice. The spiritual munshis: the two policemen spell out the conflict in the latter half of the film. Lakhna, is trying to chase the justice ideal, while the Inspector Virender Singh Gujjar (Ashutosh Rana), Bhumi’s son represent the other end of the pole ( Revenge). Both find release of the mental build-up in the end of the film. Ashutosh expects it, and only plays the chor-police game, a vicious cycle, of life-death with expected nuance.

A major problem in the film was the second half. In the need to explain the narrative, the story lines of characters and also lending depth and back story to all major characters, the makers of the film got lost in their own material, so much so that it made the post-interval film draggy.

The climatic scenes between the police and Dadda, and Sushant Singh Rajput follow a similar play out. Since both characters are closely connected because of the curse they carry on their ends, their confrontations with the sole backdrop of music when they face their inner state of minds ( the five year old girl, in the encounter) who stands as a beacon of justice, was very similar. It took the film somewhere.

The exchange between Phuliya Devi and Bhumi is interesting. Phuliya’s contention that women are a different breed altogether, far below the caste system that is perpetuated and followed by men, is a hard hitting reminder of the society and the hypocrisy we still live in.

Dadda’s following of the dharma, which gives the Gujjar inspector a chance to avenge the injustice on his community committed (unintentionally by Man Singh and his gang) is a moral trope in the film that weighs too heavy on the heads of all, particularly Lakhna, the other half of Bajpayee.

The two indifferent gods, who spell out the spiritual themes of the film, are not above the gang wars and the politics that engulfs everyone in the ravines. In fact, the politics of land and mind are closely intertwined. The two being Thakurs, after all, avenge the death of their clansman-caste man-Thakur Man Singh in the last scene of the film. One of them loads the rifle to kill Ashutosh Rana, who turns and smiles (like he knew it all along) at him as if resigning to this “law of the nature’’ fate. The soundtrack of Rekha Bhardwaj’s “the food chain poem” is played in a blackout which clearly leaves us with the feeling that in the smoldering heat of ravines – in the political wars of gangs and lands, life has no value, it is perhaps the least important. This narrative is more about the contest between binaries of Justice and Revenge, Dharma/loyalty to rebel gang-cause and a possibility of a breakout.