Nagaland govt to disallow ‘Gau Mahasabha’ in Kohima

The Nagaland government on Wednesday announced that it would not allow the holding of ‘Gau Mahasabha’ and Gau Dhwaj Sthapana Bharat Yatra in Kohima on September 28.

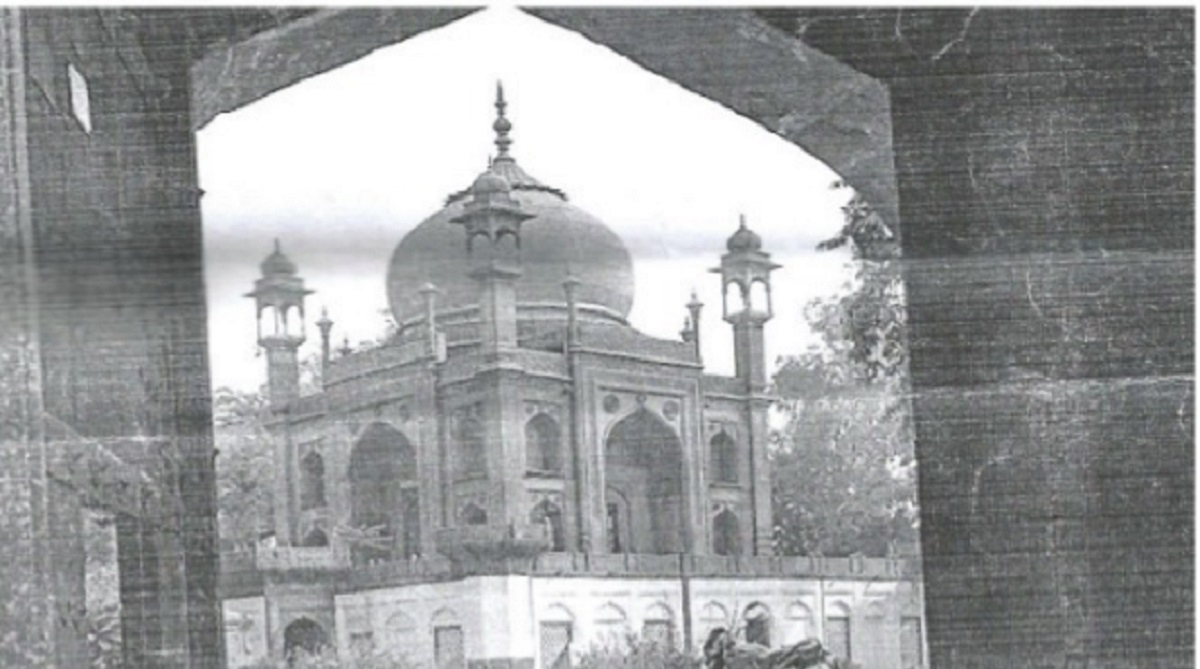

The Red Taj is the tomb of the Dutch mercenary John William Hessing, who fought in several battles for Scindia, was wounded multiple times and earned a reputation of a good man and a brave soldier

The Red Taj as depicted in the article

At the Roman Catholic Martyrs’ Cemetery of Agra “with its Mughal legacy, the tombs are built of sandstone more than marble, and their design makes them appear more Muslim than Christian”. Inscriptions on many of the headstones are in Persian script and if it were not for the crosses atop, it would be difficult to identify them as actually Christian, according to a treatise by Deepanjan Ghosh.

Here are some excerpts from it: “In the early days of European contact with India, it was quite common for Europeans to adopt Indian customs. William Dalrymple has written about English factors in Surat, who were encouraged to adopt Indian dress and diet to keep them from falling sick in a foreign country. It was common for the Sahibs to take Indian wives or “bibis” for their harems. If Indianness was leaving its mark on diet and dress, there is little surprise that it would show up in tomb architecture as well, as it does at the tomb of “Hindoo” Stewart in Calcutta’s South Park Street Cemetery.

Advertisement

He was an officer of the East India Company, who adopted the Hindu culture and religion, bathing in the Ganges daily, worshipping Hindu deities and foregoing beef.” The Agra Cemetery is the oldest Christian burial ground in North India. The first Portuguese priest to meet Emperor Akbar was Julian Pereira who arrived at Fatehpur Sikri in March 1578 from Bengal. He had been introduced to Akbar by Pedro Tavares, the Portuguese commandant of Satgaon (today’s Adi Saptagram).

Advertisement

Seeing that Akbar was deeply interested in Christianity, Pereira advised that he should send for Jesuit missionaries from the College of St.Paul in Goa. Akbar dispatched an ambassador, Abdullah to Goa with a message that two learned priests he sent to his court with the chief books of the Christian Law and the Gospel. “A committee of bishops was convened to decide on the matter and they chose three priests for this mission ~ Rudolf Aquaviva, an Italian from a noble family, Antony Monserrate, a Spaniard from Catalonia and Francis Henriquez, a Persian from Ormuz who was a convert to Christianity from Islam. They set off from Goa on 17 November 1579, arriving at Fatehpur Sikri around 27 February 1580”.

Another Jesuit came on 6 April 1590. He was a Greek sub-deacon named Leo Grimon who arrived at the Mughal court in Lahore. Grimon found Akbar deeply respectful of Christianity, even celebrating the Assumption of the Virgin Mary that year. Then a team of three was sent by Goa: Duate Leitzo, Christoval de Vega and a lay brother named Estevzo Ribbeiro.

“They were received cordially, given a house within the palace in which to live, and were even permitted to start a school for the sons of noble families.” But since Akbar would not be converted, the team returned to Goa. “Having failed twice before, the Jesuits decided to put together a ‘dream team’ of missionaries for their third attempt: Jerome Xavier, a grand-nephew of St Francis Xavier, Father Emmanuel Pinheiro, and Brother Benedict de Goes; all supremely competent men. They were met at Cambay (Khambhat) by Akbar’s second son, Murad and finally arrived in Lahore on 5 May 1595.

This team remained with Akbar, moving with him from Lahore to Agra in 1598. The emperor permitted them to build a church, and thus, “Akbar’s Church” was erected in Agra the following year. After Akbar’s death on 17 October 1605, Emperor Jahangir was even more liberal, permitting them to preach and convert. By this time ~ the early 17th century, there was already a significant Christian settlement in Agra consisting of both Europeans and some native converts.

As a result, several churches and cemeteries sprang up all around the city.” Father Eugene Moon Lazarus of the Archdiocese of Agra disclosed to the writer of the Internet article Deepanjan Ghosh that there are only three active cemeteries: The Roman Catholic Cemetery near Bhagwan Talkies, another one near Tota-ka-Taal, and the third the Cantonment Cemetery (Gora Kabristan). The Roman Catholic cemetery is called the Lashkarpur Cemetery. “Sir Edward Maclagan writes in his book, The Jesuits and the Great Mogul, that on All Souls’ Day in 1610 or 1611, several earlier Christian tombs were exhumed and their contents reinterred in the cemetery.

Apart from these, there are two small cemeteries attached to Akbar’s Church and the Cathedral of the Immaculate Conception, with priests being buried in the former to this day. “Among the inactive cemeteries, there is the Protestant cemetery, now in ruined condition attached to St. Paul’s Church, in a neighbourhood called Bagh Farzana. This was the burial ground of the old Dutch factory that once stood on the land now occupied by the Church”. There is also a cemetery inside the Agra Fort, in an area occupied by the Army, therefore out of bounds for tourists and visitors. In his book, List of Inscriptions on Christian Tombs and Tablets of Historical Interest in the United Provinces of Agra and Oudh, the British civil servant Edward Arthur Henry Blunt mentions several standstone burials hereabouts.

“But mystery surrounds another cemetery mentioned in several texts as having been a mile north of Lashkarpur on a road that Maclagan calls ‘Puya Ghat Road’. This is, in all likelihood, Poiya or Pohiya Ghat Road in modern Agra. Maclagan writes that it ‘includes the tomb of at least one descendant of the Armenian Mirza Zulqarnain’, (regarded as founder of Mughal Christianity) which was covered by a dome,” but this cemetery is difficult to find.

A source in Agra, Wasim Beg, assured Deepanjan Ghosh that it does indeed exist in the Dayalbagh area, near a residential colony called “Basera”. The land upon which Agra’s Roman Catholic Cemetery stands is thought to have been granted by Akbar to Mariam Pyaree, a pious Armenian lady. Among those buried here are several members of the Bourbon royal family of France. Besides the Armenians, a large number of headstones too are inscribed in Portuguese and Latin.

The cemetery also has the tombs of Padre Santus, a highly venerated Portuguese priest, John Mildenhall, the merchant who was the first Englishman “to see Akbar face-to-face”, the controversial “designer” of the Taj, Geromio Veroneo, the military adventurer Walter Reinhardt Sumroo, husband of Begum Sumroo of Sardhana, Ustad Nazar Khan, who cast the famous gun Zamzamafor Ahmad Shah Abdali in 1761, and the Ellis family monuments, the last member of which buried there was journalist Fred Ellis, who was more than two years older than Gandhiji and died in 1937.

But the memorial is cracking up for lack of repairs. “Without a doubt, the Red Taj is the star attraction of the cemetery. This is the tomb of the Dutch mercenary John William Hessing, who was born in Utrecht, on the 5 November, 1739 and came to Ceylon in 1757 in the service of the Dutch East India Company”. Five years later he returned to the Netherlands, then came back to India in 1763, this time joining the service of the Nizam of Hyderabad. By 1784, he was serving the Maratha chieftain Mahadji Scindia.

He fought in several battles for Scindia, was wounded multiple times, and earned a reputation of a good man and a brave soldier. Disagreement with Benoit de Boigne, the French commander of Scindia’s forces, compelled him to resign his commission. However, Mahadji had taken a liking to him and made him the head of his “Khas Risala” or personal bodyguard. It was a position he held until Mahadji’s death in 1794 but continued under his successor, Daulat Rao.

Hessing attained the rank of Colonel in 1798 and became the commandant of the Agra Fort, where he remained until his death on 21 July 1803. His son George Hessing is described by historian H.G. Keena as “a man of crude tactics and doubtful military merit”. Notwithstanding this, he was a rich man, with a personal fortune of more than 500,000 rupees. At the outbreak of the Second AngloMaratha War, when Gen. Lake laid siege to Agra, George’s own men imprisoned him, suspecting him of having associations with the British. They ultimately released him to negotiate their surrender. Col. George Hessing retired to Chinsurah and from there to Calcutta.

He died on 6 January 1826 in Garden Reach and was buried in the South Park Street Cemetery, Kolkata. Hessing’s tomb is a copy of the Taj Mahal but in red stone. Steps allow access to the upper deck where an ornamental grave may be seen under the dome. However, this is merely for show, with the actual grave being below.

The ground level is surrounded by “jaali” screens on all sides and has doors to the “taikhana” (underground chamber). Unlike the Taj, however, the tomb has no corner freestanding minars. It cost Rs 100,000 (an enormous amount in those days) and was erected by his widow, Anne, who died in 1831 in Barrackpore.

Surprisingly, the Hessings are still living and working in India, says Ghosh in his illuminating article.

Compiled by R V Smith

Advertisement