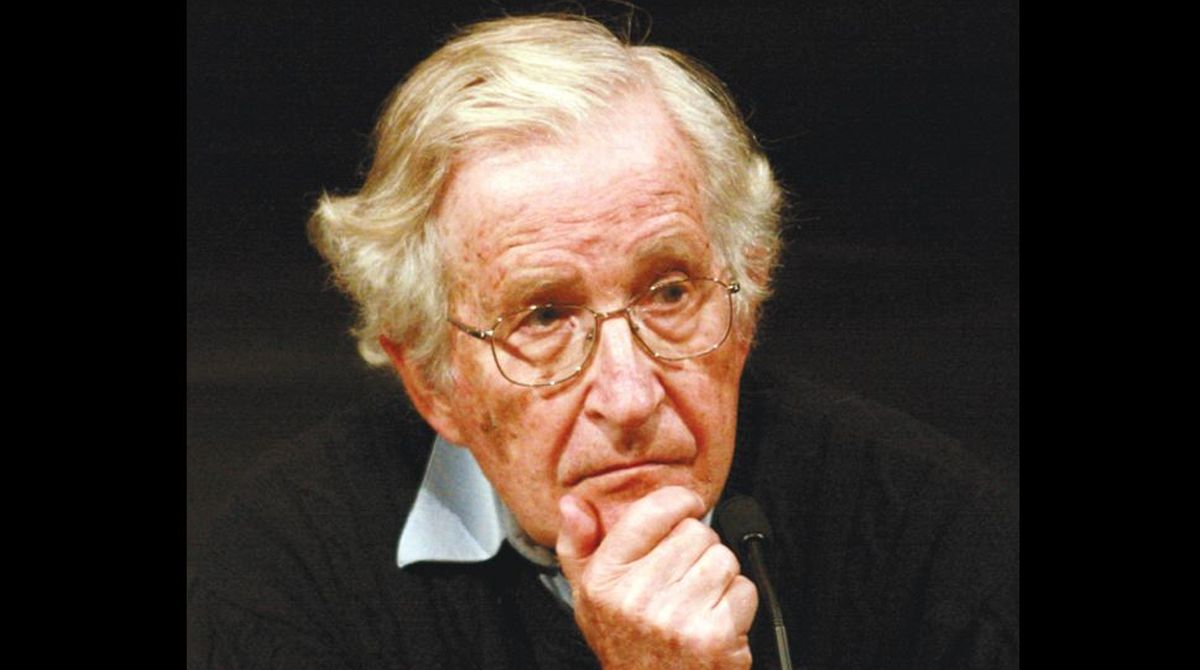

At 90, he remains a stealth dagger through the heart of our country’s illusions about itself,” Bruce Springsteen eloquently declared at a Madison Square Garden concert celebrating fellow singer-songwriter and indefatigable activist Pete Seeger’s landmark birthday.

His description applies equally well to Noam Chomsky, who turns 90 on Friday. For well over 50 years he has methodically punctured official American pretensions with inconvenient facts, attracting much love and admiration as well as considerable hatred for his mild-mannered audacity.

Chomsky initially acquired renown within academia as a groundbreaking master of linguistics. I suspect I first encountered him in books of quotations, which frequently cited his instance of a grammatically legitimate but semantically absurd sentence: “Colourless green ideas sleep furiously.”

I am unqualified to comment on his sometimes contentious theories in this field — which treat “language as a uniquely human, biologically based cognitive capacity”, as the Encyclopaedia Britannica puts it, and which acquired greater acceptability as they evolved — but what undoubtedly excited wider controversy was his decision in the 1960s to supplement his academic pursuits with political activism.

Some 30 years earlier, at a rally in London relating to the Spanish civil war, the American actor and singer Paul Robeson had announced: “The artist must elect to fight for freedom or slavery. I have made my choice. I had no alternative.” Chomsky felt the same way about intellectuals. Coincidentally, his interest in world affairs was first reflected in a school essay he wrote at the age of 10 or so, lamenting the fall of Barcelona and the triumph of Francoist fascism.

A communist uncle was instrumental in stimulating teenage Noam’s fascination with politics, but even as a young man he leaned more towards anarcho-syndicalism or libertarian socialism. In the 1950s, he even toyed with the idea of settling down in an Israeli kibbutz, a way of life that seemed closest to anarchist ideals, but he and his wife, Carol, decided against it after a month-long experimental sojourn. If Chomsky’s active participation in the movement against the US invasion of Vietnam threatened his career and liberty, his critique of Israel after the 1967 war stirred even greater ire.

It would be fair to say that in recent decades Chomsky’s political texts have overshadowed his continued engagement with linguistics, philosophy of the mind, etc. This is hardly surprising, given his trenchant critique of US foreign policy, invariably laden with facts and heavily referenced, rapidly found a global audience.

It was the focus on the Middle East and Latin America that particularly attracted my attention two or three decades ago, because it was rare to encounter such clarity in explaining exactly why large segments of the population in these parts of the world were hostile to the actions and aims of Washington and its allies. But Chomsky’s horizons are unlimited and his wealth of knowledge is formidable — which came in particularly handy in analysing the aftermath of 9/11 and the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq.

A long-standing criticism of Chomsky has been that by focusing so sharply on US excesses and outrages, he blurs the domestic and international crimes committed by various other governments. It’s not hard to see how such an impression might arise, but it’s important to remember that his intent is to highlight what often gets ignored or obscured by the corporate-controlled mainstream media. (The book Manufacturing Consent, co-written with Edward S. Herman, remains an essential primer for anyone interested in the subject.)

Chomsky’s aim all along has been not just to interpret the world but to change it, and he logically sees the greatest scope for making a difference in his own country, which he routinely describes as an outstanding bastion of freedom in some respects. It could be argued he has probably exerted greater influence on minds in the rest of the world, but that’s hardly objectionable. Besides, the American mood has lately been changing, as evidenced by the 2016 Bernie Sanders campaign and, more recently, the election to congress of the likes of Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez and Rashida Tlaib.

Last year, Chomsky published Requiem for the American Dream, a relatively unusual foray into domestic affairs. His compatriots in particular have much to gain from engaging with the ideas he has offered up over the past half-century — which have earned him the sobriquet of the greatest living political thinker. If they do, they will find no half-baked recipes for making America great again but end up with a pretty good idea of what has gone awry, and why.

Chomsky has more than 100 books to his credit and remains an erudite and clear-minded presence on alternative TV and in the lecture hall. One needn’t agree with all his arguments in order to acknowledge him as an international living treasure.

Dawn/ANN.