Raj Bhaban rejects media reports, clarifies on bust at Raj Bhavan

Raj Bhaban has also formed a two-member panel to probe the details of reports carried in some media.

Most of the North-eastern region remains underdeveloped, unharnessed and unexplored.

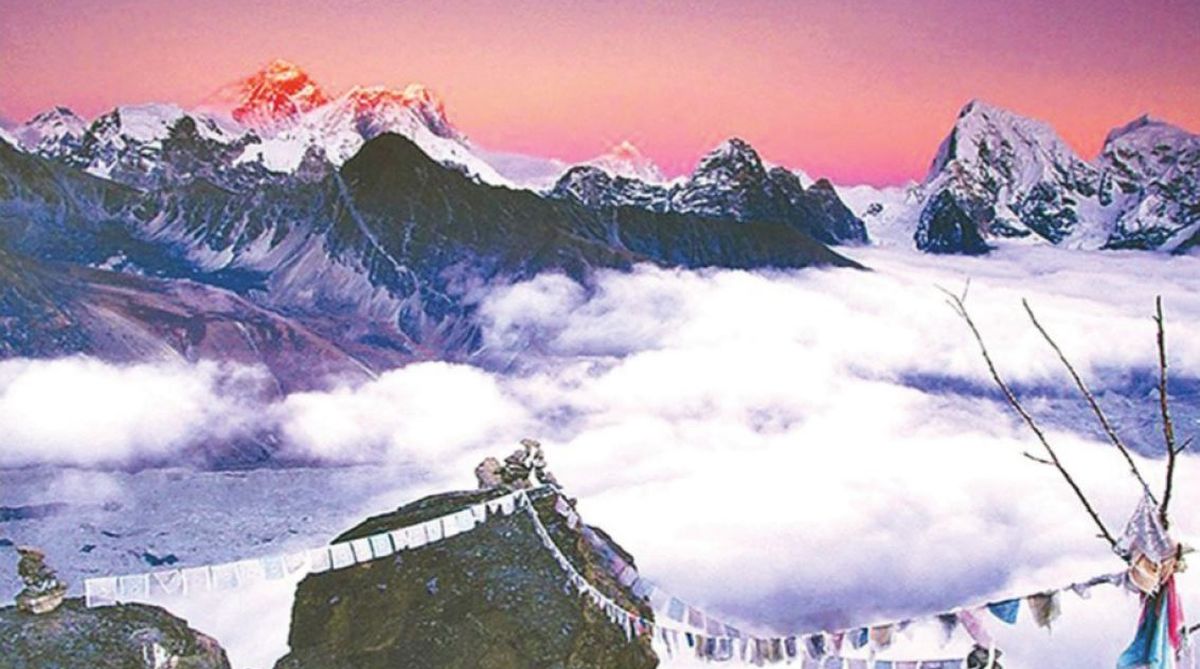

The Eastern Himalaya including Bhutan, Nepal and Myanmar and significant parts of India’s north-eastern region constitute one of the most critical and significant regions of the Indian subcontinent in terms of their crucial role in conditioning climatic conditions — as the custodian of an extraordinarily rich biodiversity, as the origin of many lifelines including the river system, and as the provider of one of the most extravagantly beautiful panoramas.

There are core strategic issues in the management of the Eastern Himalaya as it is interspersed by ancient civilisations including those of India and China. It incorporates in it the very basis of border configurations that determine the national identities and the nation-building process of at least six countries.

The North-eastern region has been one of the most prolific and potential geographies of development. However, most of the region remains underdeveloped and unharnessed in all senses of the term. There are several factors that can be attributed to the present state of affairs in the NER.

Advertisement

Firstly, the very development orientation has been based on a visible mismatch between the thinking of the planning agencies, deployment of resources and institutional backup. Development per se has always been regarded as a pure game of money and finance. For long, the Centre only pumped in money without thinking about the needs and priorities, institutions and development managers.

Since the development institutions were never set up in a planned manner, the related issues always remained in the arena of ad hocism, departmentalism and marginalism. There has been no cohesive and scientific attempt to build institutions which could provide continuance, consistence, effectiveness and sustainability to development actions. The untimely demise of India’s Planning Commission has done maximum damage to the already laggard region.

Rent seekers nexus

Secondly, the handling of the entire planning issue gives an instinctive impression that development is a prerogative and duty of only the government and state machineries. It made people too dependent on the government. It confiscated their creativity and satiated the existence of traditionally voluntary societies. The community-based development ethos – strongest pillar of the NER – was thus gradually shattered and uprooted by the actions of the government.

Therefore, in the daily life of a North-easterner today, the government is 90 per cent and her or his contribution is only 10 per cent. Private entrepreneurs and parties devoured public funds for private gains. This led to an unholy nexus between politicians, some rent-seeking bureaucrats and private parties. The insurgents who joined this team have made it the most powerful and conspicuous nexus today.

Thirdly, in a society for which the embryo of governance has been the voluntariness-based community actions, the modern type of governance based on a poor and slow trickle- down system never suited the people. This became more adversely serious as transparency and accountability became more and more farfetched.

There has been no trace of accountability, monitoring and evaluation of any development project. Spending the earmarked funds is something like pouring money into a bottomless pit. Fourthly, people from outside the region have always tended to treat the NER as a temporary resort for their rent-seeking activities. However, most of them have siphoned off the returns to their so-called home states, and many a time, to safe havens.

Even well-established private sector investors and entrepreneurs, including those in the tea plantation sector, have never ploughed back their profits. All this has kept the region high and dry in terms of further generation of income and employment. This process of siphoning off the cream of development has been institutionalised to a great degree. The consequences are well manifested in violent movements and ethnic cleansing. Discontentment and frustration, insurgency, anti-social activities, anti-non-tribal sentiments and other forms of extraction and violence thrive on these fertile emotional but substantive grounds of alienation.

The Northeast remains unexplored in many ways. That tourism, energy, biodiversity, market and human resources and its importance as a gateway to the entire East and Southeast Asia has never been effectively debated. How do we go about it? Who will bell the cat? Very few studies have been done assessing the real impact and implications of opening the Northeast both to Bangladesh and other parts of Asia. However, no one really questions the long-term transformation in the development agenda and content of the Northeast to be brought about once this sub-regionalism among Bangladesh, Bhutan, Nepal and the north-eastern parts of India is realised.

Second generation reforms and the globalisation process cannot really leave the Northeast untouched. However, the sinews of the globalisation process push forward the case for a borderless regime particularly in the economic sphere, whereas the Northeast is fighting a case for a stricter and more regulated border regime to contain migration from across the borders. What is now foreseeable is a frontal war between the forces of globalisation and its indigenous resistance.

Migration from Bangladesh has been a very critical issue, and it is likely to acquire a more deleterious dimension in the face of erosion in the carrying capacity of both Bangladesh and the Northeast. The security trail of migration could have much larger implications hitherto not discussed. The development issues in the Northeast, therefore, need to be reassessed and re-examined, keeping the perspectives of the Eastern Himalaya as a core element.

Newer definitions and paradigms including the human development approach are attractive strategies. Despite the invasion of various social media and mobile phone culture, this region has never debated the technology front. For instance, the deliberations on genetic and biodiversity resources have remained limited to textbooks and tourism pamphlets. Many of its vanishing genetic varieties have already been pirated to acquire intellectual property rights by some agencies outside the region and across the border. The surreptitious trade in medicinal plants, wildlife and gene piracy is only the tip of the iceberg.

Internal colonialism

Darjeeling, the most magnificent organ of the Eastern Himalaya, has witnessed the most unprecedented deterioration in the socio-economic system. The railway line from Siliguri to Rangpo in Sikkim criss-crosses the most fragile and vulnerable valleys of this once famous Queen of the Hills. It highlights steady erosion in its environmental surroundings.

The alternative development path provided after the violent Gorkhaland movement has been an absolute failure, both because of the continuing internal colonialism practiced by the West Bengal government and the poor understanding and utter disregard of the development issues by ad hoc dispensations like the Darjeeling Gorkha Hill Council (DGHC) and the Gorkhaland Territorial Administration (GTA).

Unfortunately, this ad hocism has already taken away three precious decades of the hill folks. It is in the interest of the Kolkata dispensation to keep the hill areas as backward as possible regardless of the cost to the nation in the future. The West Bengal government tends to shy away from taking any substantive responsibility except using law and order machineries to crush the deeply emotive identity and separate statehood upsurge.

After the DGHC and GTA experimentations hit rock bottom, what stops the West Bengal government from drawing a 10-year comprehensive development plan and implementing it day and night under the direct stewardship of the chief minister? Or what hinders the central government from devolving a ‘state within a state’ framework under Article 244A of the constitution that was implemented in Meghalaya in 1969-70? And the least that can be done would be to include Darjeeling in the North Eastern Council before the 2019 Lok Sabha polls.

The writer is a senior professor at Jawaharlal Nehru University and the co-author of the North East Vision Document 2020 for the government of India.

The Kathmandu Post/ANN

Advertisement