Amitabh Bachchan to receive Lata Deenanath Mangeshkar Award

Bollywood legend Amitabh Bachchan to be honored with the prestigious Lata Mangeshkar Award for his outstanding contributions, joining a distinguished list of recipients.

The sheer range of Salil Chowdhury’s work as a music director over nearly half a century should be enough to reflect the genius

Swapan Mullick | Kolkata | December 1, 2018 10:30 pm

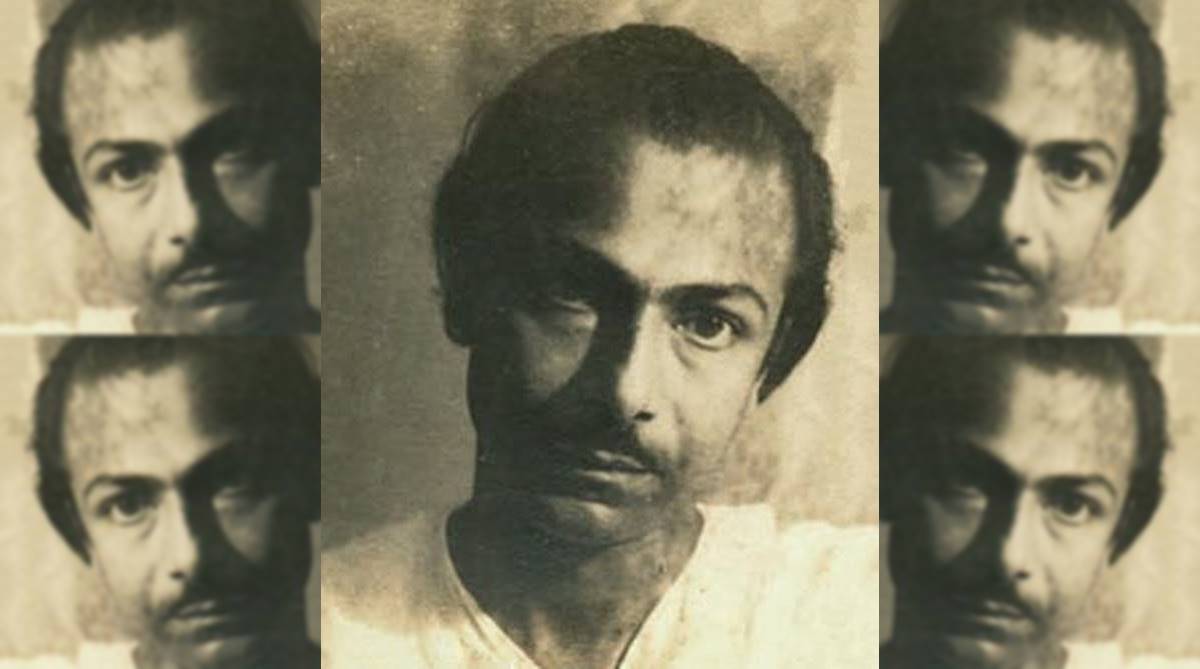

Salil Chowdhury. (Photo: Bobby Chowdhury/Wikimedia COmmons)

While the audience shared the intensity with which many of his contemporaries and admirers expressed their admiration for the music legend Salil Chowdhury on his 93rd birth anniversary, there was a depressing footnote when his daughter, Antara, confessed that it had become quite difficult to arrange a celebration even on a small scale.

The implication was that the creator of hundreds of unforgettable melodies was on the verge of being forgotten. There came instant offers to reinstall the musician in the minds of millions in all parts of the country. But that couldn’t undo the tragedy that confronts the music scene when the towering innovator is scarcely mentioned even when his pathbreaking compositions have been adapted by later generations but not with the same success.

Advertisement

The sheer range of Salil Chowdhury’s work over nearly half a century should be enough to reflect the genius. The man who broke with convention in whatever he did —whether it was composing music, writing poems and plays or experimenting with different instruments — had adapted to all kinds of situations.

Advertisement

The familiar tunes targeting the middle class milieu in Bengal in films like Barjatri and Pasher Bari in the early 50s had acquired a unique flavour but even these were set aside when he took ganasangeet to formidable heights in Runner and Ganyer Bodhu. His work was never predictable. At one point, he would be drawn into the popular realms of adhunik where singers like Hemanta Mukherjee and Lata Mangeshkar became sensational in their puja offerings.

READ | Remembering a musical genius

Soon after, there would be inspiring echoes of Western classical music that had entered his veins when, as a child living in the Assam tea gardens where his father was a doctor, he drowned himself in the worlds of Mozart, Beethoven, Tchaikovsky and Chopin.

The random overlapping of musical traditions and forms was an inspiring facet of his work that speakers at the anniversary programme recalled again and again. It had come so spontaneously that no one had ever complained of the musical ideas being borrowed.

On the contrary, there seemed to be typical juxtaposition of romance in the non-film discs and the social but still lively textures for cerebral listeners and also created for films likeEkdin Ratrewhere Chhabi Biswas was extraordinary as the drunken babu with a “moving” drum that concealed the hapless trespasser played by Raj Kapoor.

The hilarious composition had unmistakable echoes of the social concerns that had driven his association with the IPTA. The birth anniversary programme brought reassuring signals that efforts would be made to preserve important segments of Salil Chowdhury’s prodigious output. He had composed tunes for Bengali, Hindi, Malayalam, Assamese and several other films in regional languages. Some of them, inevitably, had to be made to fit into popular forms. But even in the mainstream format, he could move from enchanting melodies to structurally amazing compositions. He revealed the spirit of a restless innovator who could play a variety of instruments from the flute to the piano and the esraj while thriving on off-beat orchestration.

If his music transcended borders, it was because he kept absorbing ideas from Indian folk to the European, Latin American and Caribbean beats –—assembling it all with natural flourish. It was a pity that the anniversary programme didn’t include specimens of his music and the short audio- visual only left the audience with the thirst for a more rewarding journey into the past. It was a musical consciousness enriched by exciting hues and an early exposure to western classical as much as to the sounds of the forest and the chirping of birds — all of which he imbibed almost imperceptibly.

What came as a pleasant surprise was the film, Pinjre Ke Panchhi, the only one he had directed in 1966. The writer and musician who had turned his thoughts to the poor and down-trodden made a film that again turned to the “other half” of society — two jailbirds who escaped from a prison van, locked in a large mansion in the unexpected company of a pretty nurse and eventually reformed.

It was not the kind of film that appealed to a mainstream audience though it had Meena Kumari and Balraj Sahni in the cast with Hrishikesh Mukherjee as editor, Gulzar as lyricist, Lata Mangeshkar and Manna Dey as the playback singers and Salil Chowdhury himself as the writer. Sadly, the directorial ambitions may have collapsed because there were too many commitments on the music side. One impression was that he may have diluted his musical genius with too many related forms that otherwise confirmed his versatile achievements.

That doesn’t minimise Salil Chowdhury’s conspicuous contribution to films. It may not have always given him the creative freedom that he relished but he had left his stamp onJagte Raho, Bari Thekey Paliye, Anand, Rajnigandha, Mere Apne, Do Bigha Zameen, Madhumati and the other films of Bimal Roy that had given him a screen identity of his own.

The last word perhaps came from Kalyan Sen Barat who himself belongs to the off-beat school. He observed quite appropriately that, unlike composers and singers who belong to a specific era, Salil Chowdhury broke the time barrier.

That is why some satisfaction could be drawn from what was clearly a belated reflection on a splendid legacy

Advertisement

Bollywood legend Amitabh Bachchan to be honored with the prestigious Lata Mangeshkar Award for his outstanding contributions, joining a distinguished list of recipients.

A Sangeet Natak Akademi laureate (2018), Wadkar, 68, will be presented with a cash prize, a commendation and a memento as part of the award at a ceremony later, an official said.

For someone who has worked with the likes of Lata Mangeshkar, Asha Bhosle, Manna Dey, Jagjit Singh and has contributed to the soundtracks of popular movies including ‘Page 3’, ‘The Body’ and the recently released Nawazuddin Siddiqui-Bhumi Pednekar starrer ‘Afwaah’, the paradigm shift in Hindi film music is hard to ignore.

Advertisement