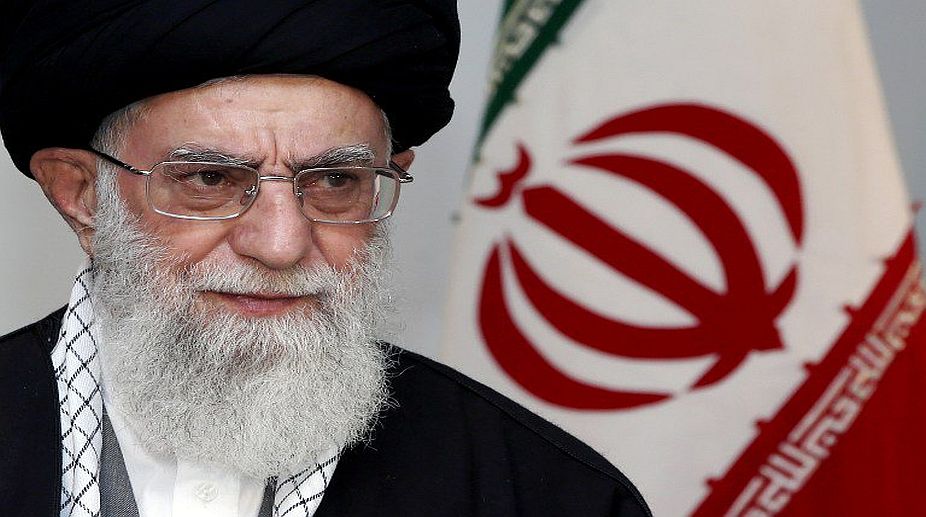

Iran has ratcheted up the pressure on Europe, whose diplomats have been scrambling to salvage the nuclear deal that is on the verge of a fizzle after the pullout by Donald Trump’s America. The new initiative, articulated on Tuesday by the supreme leader, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, unveils a plan to increase uranium enrichment.

The government in Tehran, in a way, has countered the unilateral abrogation of what must rank as Barack Obama’s signal achievement, and also of course President Hasan Rouhani’s. The plan to bolster uranium enrichment seems intended to neutralise the impact of President Trump’s impetuous move. Khamenei has made it clear that Iran will “never tolerate suffering from sanctions and nuclear restrictions”.

Advertisement

More accurately, the country will not be violating the terms of engagement. As much has been reaffirmed by Ali Akbar Salehi, the Vice-President and head of the Atomic Energy Organisation of Iran.

Under the 2015 nuclear agreement that Iran signed with world powers, it has the right to build and test certain centrifuges, although detailed restrictions exist for the first 10 years on the types and quantities of the machines. The plan has been clothed with the assertion that “these moves do not mean the negotiations with Europe have failed”.

Indeed, Europe has not concurred with Trump’s cancellation of the deal. Hence, it shall only be in the fitness of things for Iran to engage in a salvage operation. Under the terms of the agreement, Tehran can ramp up nuclear activities if the deal falters.

It would be an under-statement to aver that the deal has faltered; in point of fact it has been reduced to irrelevance by the principal signatory. Furthermore, the 2015 nuclear agreement provides that Iran has the right to build and test certain centrifuges, although detailed restrictions exist for the first 10 years on the types and quantities of the machines.

Profound has been the economic impact of the US abrogation on Europe. Governments have been scrambling to protect their businesses from renewed US sanctions in order to retain Iran in the scheme of things. But several large firms have let it be known that it will be impossible to continue operating in Iran except in the unlikely scenario that they win what they call “bulletproof exemptions” from Washington.

Britain, France, Germany, China and Russia have vowed to stay in the accord, but many of their companies have started to wind down Iranian operations. In its first assessment, the European Union has indicated the new steps announced by Iran did not constitute a violation of the agreement.

Theoretically, therefore, Iran is on a reasonably sound wicket. North Korea is a long way from Iran and Washington, and not merely in terms of distance. Yet a week before the summit, the aftermath of Mr Trump’s decision has caused a flutter in the roost.