It is magical how something otherwise discarded and thrown away can be turned into rare pieces of art. That way, the weavers of Bengal are no less than conjurers, in weaving colourful tales through motifs, mythologies, and sceneries out of a ragged fabric.

The idea of Kantha embroidery was born centuries ago to make good use of cast-off textiles. They were recycled into wrappers or quilts, which with time, also extended to decorative pieces, sitting mats and even bedcovers. Thus the womenfolk from rural Bengal would spend their lonely afternoons by transforming threadbare clothes into utilitarian products.

Showcasing the best of these works of art, the Crafts Council of West Bengal presented “Eye of the needle”, at The Birla Academy of Art and Culture, Kolkata. The festival is open for public viewing and sale till 13 May between noon to 8 pm. There were in display a range of Kanthas from Arshilata (Mirror wrapper), Durjani Katha and Ashon katha to Sujni Katha and Bostani (wrapper) among others.

The Arshilata Kantha, which was used to wrap mirrors, comes in long rectangular shapes. In the fabric has been weaved nine figures, six of which looks like women from the royalty. Their long flowing gowns and veils, each with a variety of patterns like checks, waves, and short vertical lines in red and blue calls for a diverse view. The other three figures of a little girl in frock, a turbaned man and another seated figure has been divided from the royal ones by a vine of flowers.

The Durjani Kantha, which serves as a decorative pocketbook, is decked in rich floral patterns predominantly in red and blue. The bostani, which is used for wrapping valuables, displays a range of motifs like fishes in one side to elephants in the other. The other two sides include flowers and hearts. A chakra pattern on the centre is surrounded by elements of nature, Hindu deities and tribal women on a peacock boat. On the opposite side is a pair of dancing peacock symbolising fertility.

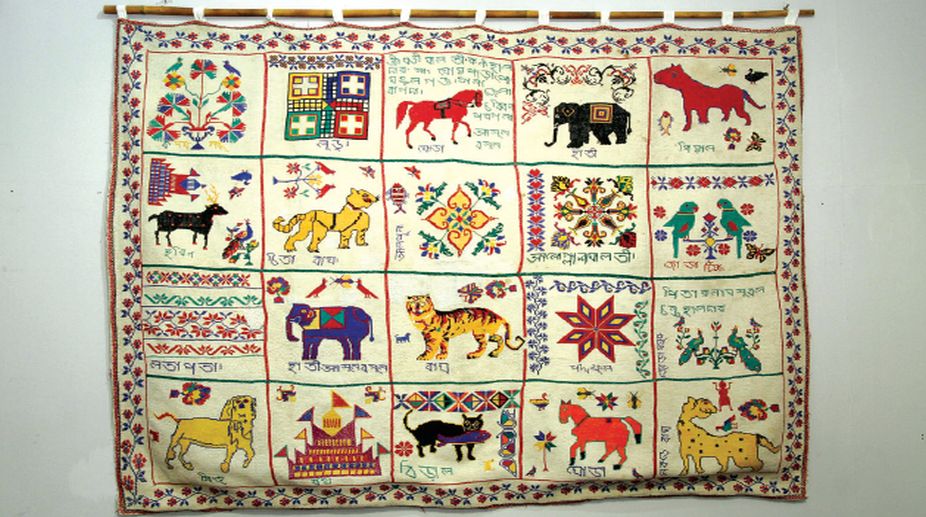

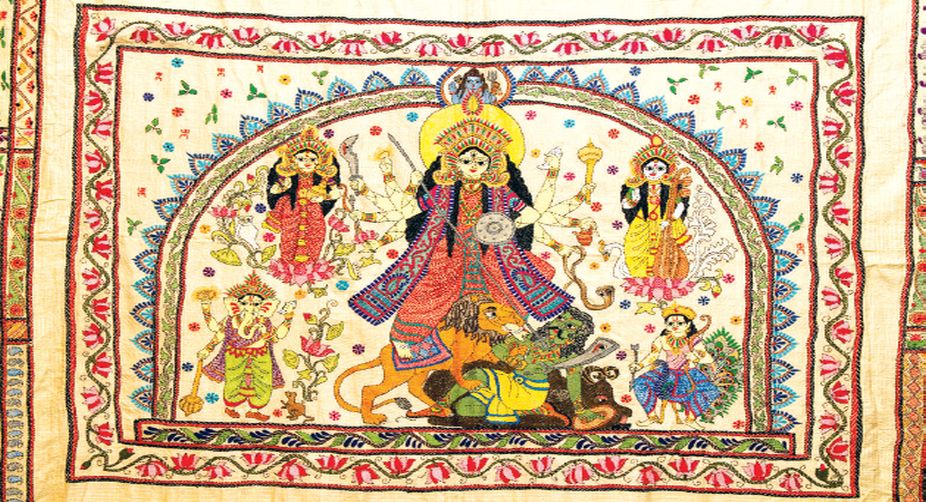

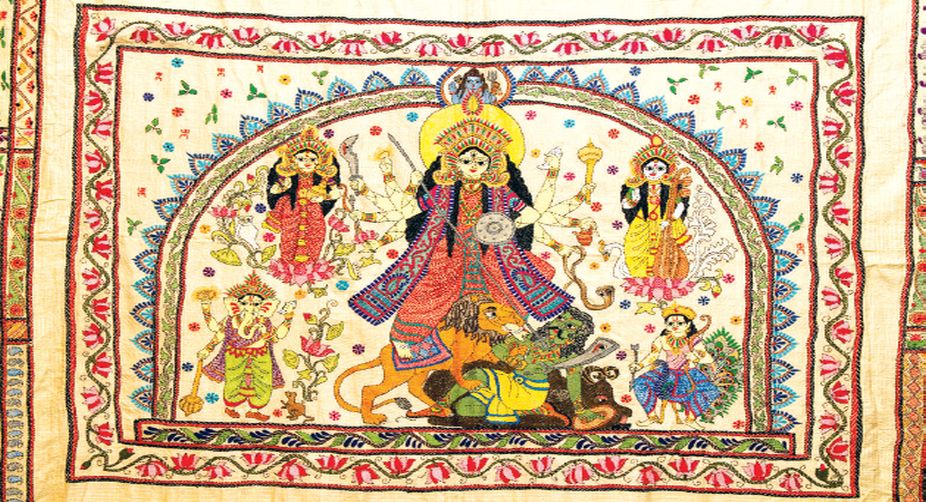

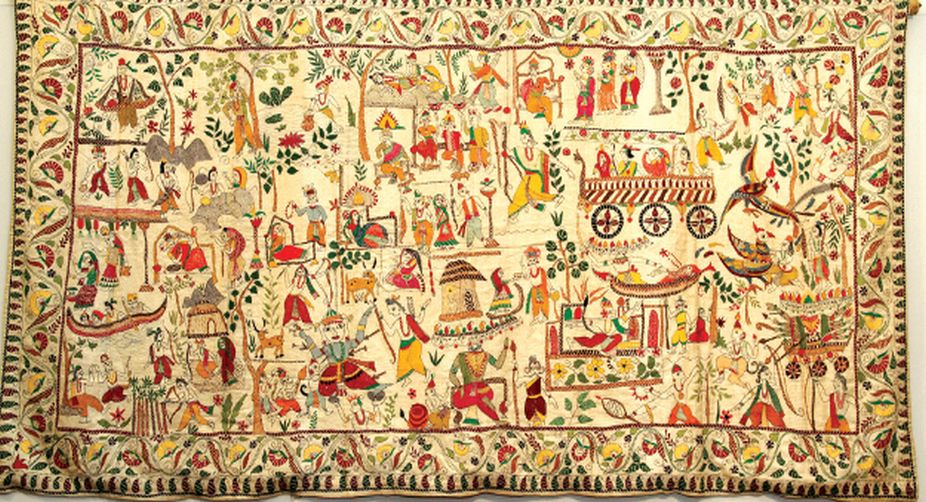

The Ashon Kantha which is used as seats for guests is abounding in animal and festival motifs conveying an essence of carnival. The images include a man sitting on a vibrantly decked elephant, a lion in blue, red, green and yellow stitches with a Hindu Goddess seated on it, colourful rathas being drawn by horses with Lord Krishna and Radha on them. A bright geometric pattern in the middle around which these images revolve gives the feel of an optical illusion, inducing life to the surrounding images.

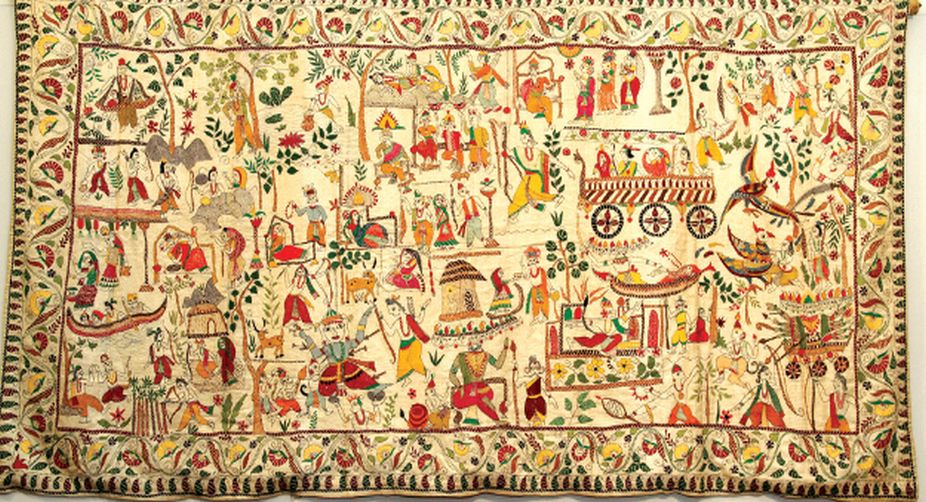

With the advent of guests, the household livens up into a festive mood. Thus the Ashon Kantha with such diverse motifs was apt as the ultimate expression of hospitality. One of the Kanthas on display was an illustrious depiction of the various episodes of the epic poem Ramayana from Ram’s exile to the forests for 14 years till when Ravana’s kingdom of Lanka is burnt down by Hanuman. The figures look as bright and colourful as in a children’s picture book.

Another Kantha with intricately designed branches of a tree looked more like an Alpona, a form of art pattern in Bengal. Two birds sitting intimately on one of the branches and two on its roots with their wings unfurled, added a poetic touch to the piece.

All the pieces with images and patterns etched out from a maze of colourful strings are a visual treat. They remind us of the simplicities which render an ethereal quality to the rural Bengal.