Drug peddler with international links nabbed from Lajpat Nagar

The accused has been identified as Hasan Raza, an Afghan national, who was arrested on Thursday night. Following the arrest, the police recovered 512 grams of heroin from his possession.

The dealer in old lamps is called a kabari now, because the art of turning old lamps to “new” ones is fast vanishing, as is the story of Aladin and his Magic Lamp

Wee Willie Winkie: Icon of children dreams .

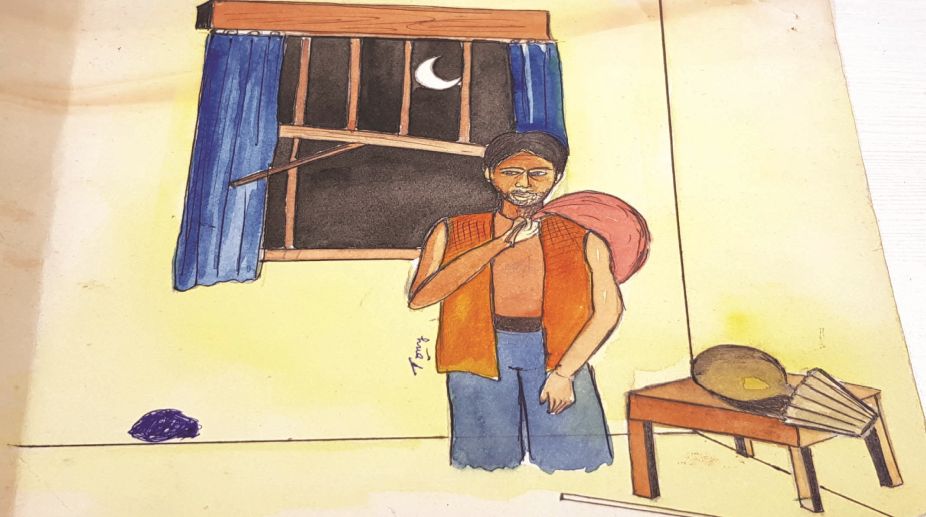

Fifty-eight years ago, the lamplighter was a familiar sight in downtown areas. He came at twilight, trimmed the wicks of the lamps installed at street corners, poured some kerosene into them and set them alight with the captive flame he carried in a lantern.

Children followed him from gali to gali, as he walked slowly with a ladder on his shoulder, set it up against a wall and climbed to the lamp he had to tend.

Advertisement

One particularly remembers Lachhoo, a refugee from Sindh, who had become a lamplighter for want of other employment. The municipality was even then a poor pay master, but he didn’t mind working for it so long as he could meet his monthly expenses.

Advertisement

One met Lachhoo 30 years later in Lajpat Nagar. He was a middle-aged man then, married and earning a decent salary. His lamp lighting days were far behind him. But still he looked back at them whistfully, for that was the first job he had ever got when he came on a crowded train to Delhi ~ glad that he was alive.

“The whole day I was practically free to do as I pleased and only early in the evening made my way to the municipal office to get the daily supply of kerosene, wicks and lamps (to replace defective ones).

By 6.30 in winter and 7.30 in summer my work was done. A short morning visit was required to blow off lamps which were still burning, but mostly they got extinguished themselves as the supply lasted only till dawn,” he disclosed with a laugh.

Lachhoo’s children were studying in college and his wife was a teacher. Things had changed for the better but still the romance of the lamplighter was hard to extinguish. “Do you know, I fell in love with a girl while making my rounds. Don’t tell my wife,” he added with a wink before boarding a bus back home. Now about his predecessor:

Seventy years ago, Qamaruddin was the lamplighter of our locality. He lived in a mohalla built over a nullah . Hence its name ~ Nullah Burhanuddin. Named after a local saint, it was home to hundreds of people, who earned a livelihood doing odd jobs.

Qamaruddin considered himself lucky that he was at least assured of a monthly salary from the municipality. He had a wife, five children and old parents to look after. But they made do even on short commons ~ eating roasted gram for breakfast, left-over dinner curry for lunch and the main meal in the evening.

The whole day Qamaruddin would sit in a Takia (compound of a sayyid’s grave) and play pacchisi or Indian chequers. So engrossed was he in the game that he more often than not even forgot to have his lunch.

Some thought he did it deliberately so that his children could have an extra helping. Illiterate he was, but saw to it that the kids went to a madarasa school and, besides the Quran, learnt some Urdu, which was then the second language used in court.

As children we would at times sit near Qamaruddin when he was not playing chequers. “You are the sahib’s progeny, staying in the big house beyond our mohalla, come to hear stories in your free time,” he would say with a chuckle. And then the tales began ~ of princes and princesses (Amrood-di-Badshahzada, Narangi-di-Badshahzadi and Sunheri Seb-ka-Shehzada). The afternoon was too short for the story to endand it was invariably carried over to the next “free day”.

But Qamaruddin’s best yarns were the ones based on his experiences as a lamplighter: The banshee who broke lamps at midnight; the madwoman who wailed when the lamp got blow off; and the pretty bride who made it a point to greet the first lit lamp of the evening.

In 1947 Qamaruddin and his family packed up to go to Karachi. Whether they made it safely is not known, but a rusted broken lamp on a gali wall keeps the old lamplighter’s memory alive ~ and of his successor, Lachhoo Sindhi.

His counterpart was Boondan, the lantern seller, who used to appear in the streets of Delhi at dusk. He walked with a slow, swinging gait, making the dozen-odd lanterns hanging on his shoulder flicker merrily. The urchins heralded his approach with shouts of “Batiyonwala Budha aa gaya”.

And they had reason to be glad for the bearded old man brought the warm glow of lights to ill-lit gullies, where the wicker lamp was very much in use. Kids of convent schools thought he was Wee Willie Winkie gone old after years of making his eerie rounds.

In the day Boondan collected discarded lanterns, mended and polished them. And when the evening star shone high in the sky he was out on his beat. He walked from house to house, crying, “Lalten laylo!” and patiently waited for the housewife’s response.

He used to ply the second-hand trade with relish after retiring as a street lamplighter. Selling a lantern here or releasing a wick there, moved about in the alleys, finally getting lost until the next evening. That was years ago.

Boondan is long dead and nearly all the houses, even in the dimmest of gullies, have electricity now. But frequest power-cuts keep the trade in lanterns going. The seller now is a younger man who prefers to sit near a kerosence oil dealer.

He is a factory hand, who tries to make some extra money in his free time and buyers are not wanting . However one has to be choosey with old lanterns for they might leak or just fail to stay alight.

The dealer in old lamps is called a kabari now ~ a junk buyer for sure, because the art of turning old lamps to “new” ones is fast vanishing, as is the story of Aladin and his Magic Lamp.

But when the evening star is up the children of yesteryear miss Boondan’s flickering lanterns at Chowk Matia Mahal. You may light a candle or curse the darkness but the old man is still remembered whenever there is a power failure.

R V Smith

Advertisement