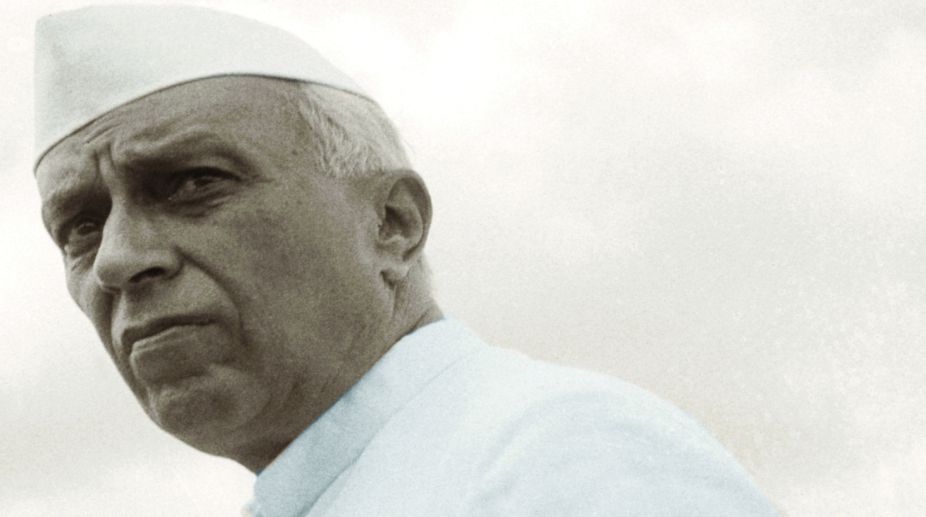

In his article, ‘A Quintessential Man’ (10 March), Mr M Riaz Hasan has paid glowing tributes to Jawaharlal Nehru, even suggesting ~ without any explanation ~ that he was capable of becoming the Prime Minister of the United Kingdom or the USA.

He cites Nehru’s role during the Suez crisis as one major example of his heroism. But he does not refer to the Prime Minister’s contradictory policy in Hungary regarding which Kiran Nagarkar writes: “Nehru’s response was muted. Politics has truimphed over moral stance”.

Mr Hasan refers to Nehru’s literary works, but fails to mention that during the Gandhian era there was a change in the British attitude to the newly-emerging political class with a hazy formulation of transfer of power in which this new political class would play a pivotal, if not a decisive, role.

The incarceration of the Mahatma in the Aga Khan Palace, Pune, in the wake of the 1942 Quit India movement was a clear indication of this. The political prisoners were treated well with enough leisure during which time Nehru, with help of Maulana Azad, wrote three well-written books.

This is in sharp contrast to Tilak’s imprisonment in the 1890s when he was just a common prisoner and was not even allowed to read the Gita. This was permitted only after Max Mueller’s intervention.

In Discovery of India (1946), published just before Partition and Independence, Nehru wrote about corruption during British rule. He blamed the British for this miserable condition in which hundreds of thousands of Indians were poor, with only a small minority being prosperous.

He also criticised the British for completely ignoring people’s welfare. In the immediate aftermath of Independence, when there was an acute shortage of foodgrain, Nehru publicly said that he would hang the blackmarketers from the nearest lamp-post.

Corruption afflicted Indian politics at the very beginning of the Nehruvian era. VK Krishna Menon, Indian High Commissioner to Great Britain in 1948, bypassed all norms to sign a deal worth Rs 8 million for the purchase of jeeps for the army.

Most of the money was paid upfront, but only 155 jeeps were supplied when the stipulated number was 200. Nehru, instead of ordering an enquiry, had forced the government to accept it.

Govind Ballabh Pant was the Home Minister at that time and he rejected the suggestion of an inquiry committee, led by Ananthasayanam Ayyanger. The scandal was hushed up and the government announced on 30 September 1955 that the jeep scandal case was closed and there would be no judicial enquiry. The government even went to the extent of suggesting that if the opposition was not satisfied it could make it an election issue.

In February 1956, Menon was inducted into the Nehru Cabinet as minister without portfolio. He was subsequently elevated to the important position of Defence Minister, ignoring his role in the jeep scandal. Mahatma Gandhi’s Personal Secretary, UV Kalyanam, remarked that Nehru had appointed corrupt colleagues like Krishna Menon as the Defence Minister.

By 1956, corruption had become endemic and in the Mundra deal, Feroze Gandhi exposed the prevalence of corruption in exalted levels. This culminated in the resignation of TT Krishnamachari, who was then the Finance Minister.

But there was no large-scale effort to cleanse the system. A larger number of Congress leaders were found to be corrupt but no penal action was ever taken against them.

Mr Riaz Hasan is impressed with Nehru’s role as Prime Minister. The seamier side of Nehru had disastrous consequences. He was extremely power conscious and, unlike Gandhi, was reluctant to build up a team.

Indeed the very essence of parliamentary democracy, intra-party democracy and the spirit of free speech, were absent in the Congress under his stewardship.

The distinguished journalist, Inder Malhotra, had once remarked: “Nehru’s greatest failure was also in the area of his prime expertise. It was his heavily flawed China policy that led to our humiliating defeat in the brief but brutal border war with China in 1962, which shattered him both personally and politically. Unfortunately, none among his close advisors, civilian or military, ever questioned his naïve belief that the Chinese would do nothing big. For the governing doctrine then was ‘Panditji knows best’.”

He carried an impossible work-load. As Aakar Patel wrote, “It is perfectly true that Nehru was irritable, but he was also bombastic and verbose, making too many speeches (often three a day) and spending too much time lecturing the West. He was careless with his time, once giving three hours to a high-school delegation from Australia, while his ministers waited outside”.

Nehru never distinguished the frivolous from the serious. He never treated his ministerial colleagues or even the popular chief ministers with respect.

Often, he would give them, and convey his thoughts through his letters. But the tone was generic and not specific. He did not have a system of feedback.

Patel also exploded the myth that “Chacha Nehru” loved children ~ ‘Nehru did not really have time for or enjoyed their company’. He quoted Crocker to prove his point. “Nehru certainly did some acting on public occasions. The acting was never worse than the pose of Chacha Nehru with the children.”

This keenness to be a man for all seasons and really believing that the world is a stage in which we are all actors, kept him busy with unnecessary ceremonies and actions which he could have easily avoided.

Many of his activities should have been reserved for the President, and not the Prime Minister. Patel gave two examples of Nehru’s personal acts and sensitivity.

At a meeting of Congressmen in Delhi, the members protested when they were asked to sit on the grass instead of chairs. At this, Nehru rose from his chair and sat on the grass… ‘silencing them all immediately’.

The wide gap between policy and implementation is a legacy of the Nehruvian era that followed the Fabian collectivist model. Nehru neither had the patience with details nor a team to really lead the nation that was in its infancy.

He continued with a top-heavy urbanised colonial set-up without any reform. Nor did he empower the poor with proper education and healthcare.

In contrast, the East Asians did not set up any IITs, but put in place a network of institutions for proper basic education and skills, a point that was acknowledged by Galbraith in the 1990s when he remarked that it is impossible to defeat the East Asians as they have no paucity of technically qualified manpower.

The great advantage that India had at the time of Independence was an organised political party and an efficient merit-based bureaucracy. Both were squandered by Nehru with his superficial modernism and over-centralisation of power and authority.

The writer is retired Professor, Department of Political Science, University of Delhi.