Baradin aiya lal patti Laya” ~ that’s what X’mas is like in Delhi, with its blooming chrysanthemums and marigolds. The first is named after Christ and the second after Mary ~ or at least this is what the belief is here and elsewhere.

White Christmas in India is confined to the hills and Kashmir ~ otherwise it’s a brown X’mas throughout the country, with people in Kerala and Chennai sweating it out. So the traditional Christmas acquires an Indian touch because of climatic and social factors. Do you know there is even a ghazal by Sir Florence “Matlab” Filose on Jesus Christ?

Alfred J Edwin, a Delhi-based writer, observed over 30 years ago that the popular image of Christmas, “which built up over the past 200-300 years, overshadowed the true significance of the occasion. This was primarily in the overall context: the image of Burra Din of the Burra Sahib from abroad described Christmas Day… it was the bacchanalian image which stood out…Evidently X’mas came to India much before the representatives of the West set foot on Indian soil…going back to the time of the Apostle St Thomas” in the first century AD.

Along with Dr Charles Fabri, Gertrude Little, Thomas Smith and Raj Chatterjee, Edwin was among the principal contributors to the Delhi paper in the fifties, sixties and seventies. He goes on to say, “In the last quarter of the century the western influence has receded and Christmas in India has fallen in line with many other festivals (of the country)…Indian carols are characterised by their brisk tempo, like the Punjabi hymns and some of them are ideal for group singing. This is not to say that the grandeur and majesty of Handel’s Messiah have been forgotten”. But along with it “Naman Naman Balak Yesu” also has its charm when sung in rustic baritone by the Bhajan Mandali of the late Fr Adeodatus. There were also the minstrels of Brother Noel singing the alto Yesu a-a-a).

One of the articles Gertrude Little wrote is still memorable. It was about the crib (tableau of Christ’s birth) at the Cathedral of the Sacred Heart, in which a hen had laid an egg. On Christmas morning, the sacristan (the man who looks after the upkeep of the church and assists the priest in other ways, beside ringing the bell) was pleasantly surprised to find the egg lying within easy reach of the Baby Jesus, with his mother and father (rather their statues) looking on and the Good Shepherds and Wiseman in the background gazing in wonderment.

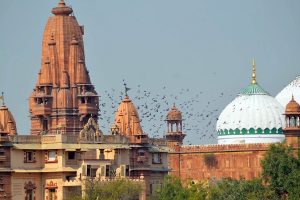

Whose hen it was that had come to pay its own tribute to the Christ Child could never be established. It had probably strayed in from the servants’ quarters facing Gurudwara Bangla Sahib, where some poultry was kept to supply desi eggs to the Archbishop’s kitchen. Probably it was the Most Rev Mulligan, who was the incumbent prelate at that time. Incidentally, a pair of silver bangles was once presented to the Divine Infant by a Brahmin woman. Thomas Smith contributed articles to The Statesman on Christmas and New Year’s Day of the Mughal times ~ from Akbar to Jahangir, as Shah Jahan and Aurangzeb were more orthodox, but not so some of their successors. The celebrations in Akbar’s days included a Christmas play, in which boys and girls dressed up as angels and the Magi (in medieval robes) came on camels to the church, guided by the big star they had seen. The actors were members of the cosmopolitan community, composed mainly of the European merchants ~ the English, French, Armenian, Flemish, Dutch, Spanish and Danish.

Margaret Chatterjee, who taught at Miranda House, saw the Delhi Xmas scene not through the eyes of an Englishwoman but those of a kindly friend, who had settled down in the Capital. She wrote on Christmas music and the somnolent tunes of “Silent Night”, savouring Carlton cakes and Bombay House pudding the next day, when others enjoyed Ruby Irene’s “pakwan” and Evelyn aunty’s mince gujias, washed down with tea or coffee.

Edwin mentioned the Christian influence on Indian art right from the time of Akbar, “mainly under the influence of the Jesuits”, the paintings of Miriam as the Madonna done in 1600-10 showing “Mary in a graceful posture with the peacock in the foreground”. In mid-20th century, Edwin quotes two painters, Alfred D Thomas of Delhi and Angelo de Fonseca of Goa (he forgot Benjam in Montrose “Muztar”) as imparting the Indian touch to Christian paintings (along with Francis Souza).

“In the Annunciation scene, when the Archangel Gabriel greets Mary, he is shown (by Alfred Thomas) as carrying a lotus flower as a symbol of peace and purity…In the Adoration scene Mary is shown seated with the Child Christ under a peepul tree…draped in yellow and brown instead of the traditional blue”. There is even a statue of the Virgin (always depicted barefoot) wearing a sari and shoes. Thomas died many years ago in Chelsea (England, but he had set up his first studio in Connaught Place). His famous first painting of the Adoration decorated St James’s Church in Kashmere Gate for many years. Now it hangs in Paulus Sadan, in Rajpur Road, Delhi.

Another person (among many), who did his bit in imparting the Indian touch to X’mas, was the late John Missal. His story “The Crib” is about a girl called Sunita, who abandons her love-child in a church near the Baby Jesus, is a deviation from the usual X’mas tale. But this one also has happy ending. The Delhi tradition has it that Santa Claus comes over the mountains from Tibet, riding a yak and not the reindeer sledge.

If Christmas comes can goodies be far behind? The markets are full of them despite all this talk of a Second Great Depression, though some term it Meltdown. The YMCA is selling plum cake, fruit cake, meat loaf, mutton and chicken patties and assorted cookies at rates ranging from Rs 350 to Rs 150 a kilo. It’s good stuff but orders have to be placed in advance. Prices in the market tend to high or low, depending on quality. After the YMCA’s Children’s Christmas Tree Party, at which Santa Claus gives away free gifts to kids 3-12 years-old, the Christmas lunch is held at Rs 75 per member. A special function is the sharing of Christmas joy with the Refugee Community. The refugees are mostly from places like Afghanistan and Iraq. Carol singing and Nativity plays as also a festival of choirs plus a chrysanthemum flower show rounds up X’mas week.

The churches, both Catholic and Protestant, are not far behind in holding their own celebrations, which begin with X’mas choirs from 14 December and last till 23 December. For Christmas Day, most churches hold Midnight Mass. It begins with carol singing from 11 to 11.30 p.m., followed by Mass in English and Hindi. On 28 December, the Feast of the Holy Innocents, X’mas Tree celebrations are generally held. For New Year’s too there is Midnight Mass, followed by Mass in the morning. Most churches adhere to a similar programme with minor alterations ~ like some having the X’mas Tree in the New Year as Christmas lasts up to 6 January, the feast of the Magi (Epiphany), who came to worship the baby Jesus. It is worth noting that people of other communities too participate wholeheartedly in X’mas and New Year’s Eve functions as the festive week has become cosmopolitan in nature, partly because of the balmy weather.

In this connection it’s worth tracing Christmas celebrations since the early 20th century. Christmas Day 1911 fell on a Monday, which meant a two-day holiday for many, since the previous daywas a Sunday. It was bitterly cold but the Delhi Club housed in Ludlow Castle (now demolished) the evening was marked by a ballroom dance. The next day the Rev A S Wallnut preached the sermon at St Stephan’s Church. At the Catholic St Mary’s Church, Fr Hillary and Father Colamba officiated while at St James’ Church there was a Christmas lunch with gifts being distributed to the poor and children.

At Baptist Church, Chandni Chowk, Hakim Ajmal Khan was among the visitors, along with Lala Chunna Mal’s family from Katra Neel. At Holy Trinity Church, Prince Sorayah Jah and Nawab Dojana were the VIPs. Following the excitement of the Coronation Durbar, Christmas Day 1911 turned out to be a memorable occasion for both Christians and non-Christians, despite the undercurrent of resentment among some of the local Muslims against the Durbar, which they considered an insult to the former rulers ~ the Mughals.