Lightning death

A couple died when struck by lightning at a farmland in Memari in East Burdwan on Friday afternoon.

Thunder and lightning have sparked awe and fear in humans since time immemorial. In both modern and ancient cultures, these natural phenomena are often thought to be governed by some of the most important and powerful gods — Indra in Hinduism, Zeus in Greek mythology and Thor in Norse mythology.

We know that thunderstorms can trigger a number of remarkable effects, most commonly power cuts, hailstorms and pets hiding under beds. But it turns out we still have things to learn about them. A new study, published in Nature, has now shown that thunderstorms can also produce radioactivity by triggering nuclear reactions in the atmosphere.

Advertisement

This may sound like the plot of a blockbuster science-fiction disaster. But in reality, it’s nothing to worry about. Since the early 20th century, scientists have been aware of ionising radiation — particles and electromagnetic waves that can damage cells — raining down into the Earth’s atmosphere from space. This radiation can react with atoms or molecules, carrying enough energy to liberate electrons from either atoms or molecules. It therefore leaves behind an “ion” with a positive electrical charge.

Advertisement

Just over a century ago, the Austrian physicist Victor Hess made measurements of ionisation in a hot air balloon five kilometres above the Earth’s surface. He noted that the ionisation rate increased rapidly with height, the opposite of what might be expected if the source of the ionising radiation was coming from the ground. Hess therefore concluded that there must be a source of radiation with very high penetrating power located above the atmosphere. He was named co-recipient of the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1936 for his discovery, later dubbed ‘cosmic rays’.

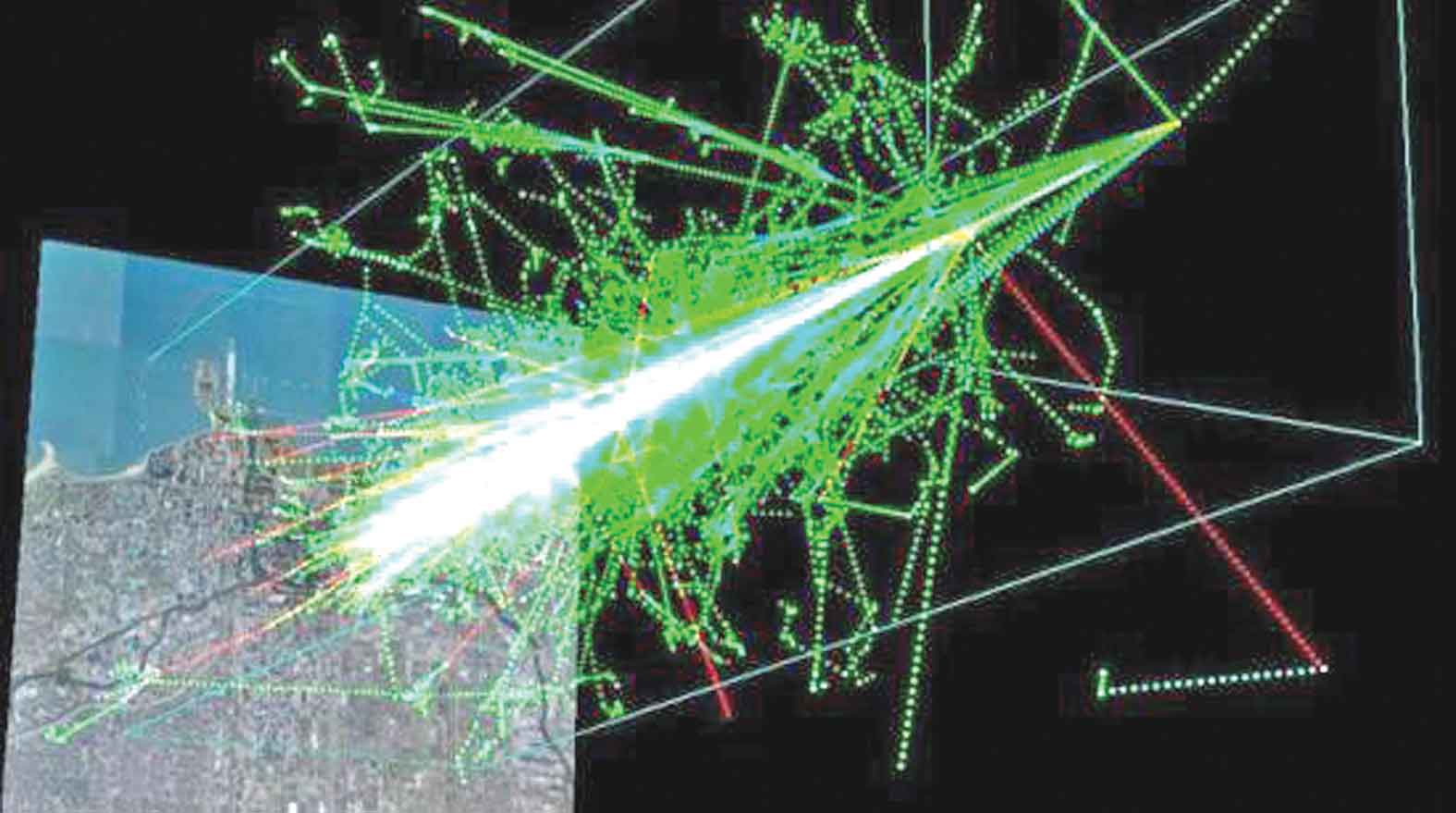

We now know that cosmic rays are made up of charged particles: primarily, electrons, atomic nuclei and protons — the latter make up the nucleus along with neutrons. Some originate from the sun, while others come from the distant explosions of dead stars in our galaxy, known as supernovas. When these cosmic rays enter the Earth’s atmosphere, they interact with atoms and molecules to produce a shower of subatomic particles. Among these are neutrons, which have no electric charge.

It is these neutrons that make radiocarbon dating possible. Most carbon atoms have six protons and either six or seven neutrons in their nuclei (dubbed isotopes 12C and 13C respectively). However, neutrons produced by cosmic rays can react with atmospheric nitrogen to create 14C, a heavy and unstable isotope of carbon that, over time, will radioactively decay (split up while emitting radiation) back into nitrogen.

In nature, 14C is incredibly rare and makes up only about one in a trillion carbon atoms. But, apart from its weight and radioactive properties, 14C is basically identical to the more common carbon isotopes. It oxidises to form carbon dioxide and enters the food chain as plants absorb the radioactive CO2.

The ratio of 12C to 14C in a given organism will start to change when that organism dies and ceases to ingest carbon. The 14C already in its system then starts to decay. It’s a slow process since 14C has a radioactive half-life of 5,730 years, but it is predictable, meaning that organic samples can be dated by measuring the ratio of 12C to 14C still remaining.

In this way, cosmic rays are responsible for nuclear reactions in the Earth’s atmosphere. Until today, we thought it was the only natural channel producing radioactive elements such as 14C. The word “nuclear”, so sinister when partnered with “bomb” or “waste”, simply refers to the changes that are brought about in an atomic nucleus.

Almost 100 years ago, the renowned Scottish physicist and meteorologist Charles Wilson proposed that thunderstorms could also trigger nuclear reactions in the atmosphere. Wilson, who undertook fieldwork at the isolated meteorological observatory on the summit of Ben Nevis, Britain’s highest mountain, was fascinated by thundercloud formation and atmospheric electricity. However, his suggestion predated the discovery of the neutron — one of the tell-tale products of nuclear reactions — by seven years, so his proposal could not be tested.

Since Wilson’s time, there have been many studies that have claimed to have detected thunderstorm-produced neutrons, but none have proven to be definitive. Others have searched for energetic electromagnetic radiation (X-rays and gamma rays) that accompanies the avalanche of high-energy electrons that we know is produced by lightning in thunderclouds. Calculations show that these electrons and gamma rays can knock neutrons out of nitrogen and oxygen in the atmosphere. But although the X-ray and gamma rays have been observed, there has never been a direct observation of the consequent nuclear reactions taking place in a thunderstorm.

The new study uses a different approach. Instead of searching for the elusive neutrons, the authors rely on other by-products of the nuclear reactions. If electrons and gamma rays cause unstable isotopes of nitrogen and oxygen to be formed by nuclear reactions following a lightning stroke, these should decay after a few minutes to form stable isotopes of carbon and nitrogen.

Crucially, this decay produces a particle known as a “positron”, the “antimatter” version of the electron. All particles have antimatter versions of themselves — these have the same mass but the opposite charge. When antimatter and matter come in contact, they annihilate in a flash of energy. This is the energy the researchers looked for. Using radiation detectors looking over the Sea of Japan, they observed the unambiguous gamma-ray fingerprints of positron-electron annihilation taking place immediately after lightning strikes in low winter thunderclouds. This is clear evidence of nuclear reactions taking place in thunderclouds.

These results are important as they demonstrate a previously unknown source of isotopes in the Earth’s atmosphere. These include carbon-13, carbon-14 and nitrogen-15 but future studies may also reveal others, such as isotopes of hydrogen, helium and beryllium.

The findings also have implications for astronomers and planetary scientists. Other planets within our solar system have thunderstorms in their atmospheres that might contribute to the composition of their atmospheres. One of these planets is Jupiter, which is fittingly also the god of thunder in ancient Roman mythology.

The writer is a professor of space physics at Lancaster University, UK

The Independent

Advertisement