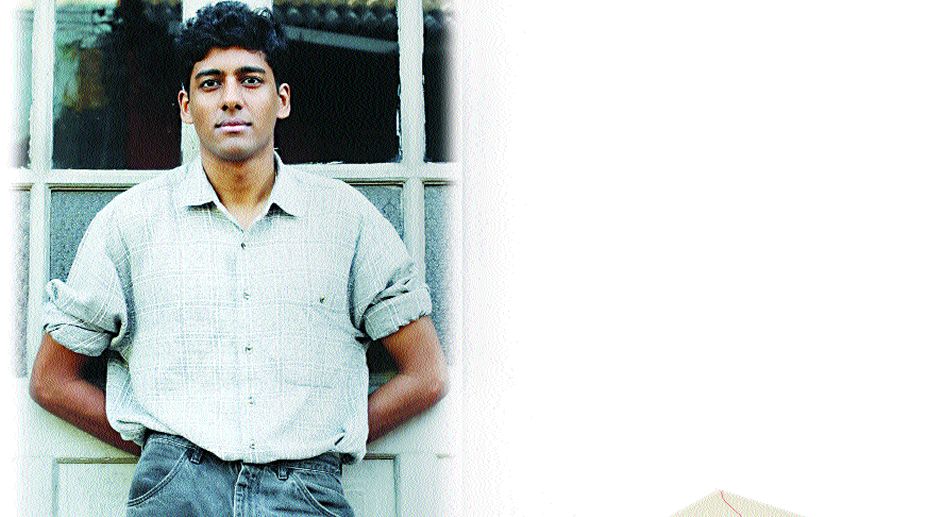

Anuk Arudpragasam is this year’s winner of the DSC Prize for South Asian Literature for his novel, The Story of a Brief Marriage. The US $25,000 DSC Prize was awarded to him along with a trophy by Mr Abul Maal Abdul Muhith, Minister of Finance of Bangladesh at the Abdul Karim Sahitya Bisharad Auditorium at the Bangla Academy for the finale event of the Dhaka Lit Fest. Anuk Arudpragasam is from Colombo, Sri Lanka and is currently working towards a doctorate in philosophy at Columbia University. He writes in English and Tamil. This is his first novel.

The DSC Prize was instituted by Surina Narula and Manhad Narula in 2010 specifically focused on South Asian writing. It is open to authors of any ethnicity or nationality as long as the writing is about South Asia and its people. It also encourages writing in regional languages and translations and the prize money is equally shared between the author and the translator in case a translated entry wins.

The book The Story of a Brief Marriage is a stirring narrative about Dinesh, a young man trapped on the frontlines between the Sri Lankan army and the Tamil Tigers. Desensitized to the horror all around him, life has been pared back to the essentials: eat, sleep, survive. All this changes when he is approached one morning by an older man who asks him to marry his daughter Ganga, hoping that victorious soldiers will be less likely to harm a married woman. For a few brief hours, Dinesh and Ganga tentatively explore their new and unexpected connection, trying to understand themselves and each other, until the war once more closes over them.

Despite a very hectic schedule, Anuk who is now travelling in the US, made time for an exclusive email interaction with The Statesman where he was candid and open in his responses. Excerpts:

Q First, congratulations! What was reaction? Did you have any inkling you would win?

Thank you! I don’t know if I had a reaction, perhaps because I didn’t expect to win. I’m still not sure what my reaction is. I’m happy, of course, for the recognition, but I suppose on the whole I’m not really thinking about it. I find I learn much more from (well-meaning) criticism of my writing than from unqualified praise of it.

Q How much of the story is based on facts?

They are amalgamations of myself, of people I know well, and people I’ve come across

Q Tell us about the characters in the novel, are they based on people in your life?

The actual plot revolves around a man trying to marry off his daughter to a stranger at the height of the carnage, in order to absolve himself from responsibility of his daughter. I read about similar things happening during the Sri Lankan army’s capture of Jaffna in 1995, and decided to frame the novel around such a story. The novel itself, though, is largely a series of images and reflections, and these came to me much earlier, in the months immediately following the end of the war in 2009, when I spent a lot of time looking at photos and video footage of what happened

Q When did the story first take seed in your mind? Where or how did you research on sensitive information on Sri Lankan army and the Tamil Tigers?

I spent a lot of time looking at images and videos. I also spent much time in the war zone in the years after the war, walking around, looking and listening, often with my friend the psychiatrist S. Sivathas, who to my knowledge was the only psychiatrist in Sri Lanka working directly within the populations affected by the carnage of 2008-9. Another psychiatrist, Daya Somasundaram, wrote a harrowing and insightful article containing testimony from survivors, “Collective Trauma in the Vanni,” which I read several times.

Q What was the most difficult part in writing this novel?

Probably the violence and darkness of the subject matter. It was a strain to think of these things for several hours a day for three years. At the end of the day it’s nothing compared to the psychological toll of actually experiencing such violence, but I was glad to be done with writing it finally nevertheless.

Q Any plans to write another?

Yes. I’m writing a novel, which is kind of a study of different forms of yearning.

Q What about your childhood, formative years? Who influenced you?

My parents do not read much themselves, but they always bought books for my sister and I to read. My mother would buy me books when I was a child and give them to me as surprise presents, and when I was older my father told me that the only thing he would buy for me regardless of the cost was books. I’m very grateful to them

Q What is your take on the increasing violence in the world?

I don’t really know, but my sense is that violence is not necessarily increasing so much as becoming increasingly visible. And I don’t really have a take on it — I’m not a political theorist or a historian.

Q Last but not the least, you announced that you would donate one third of the prize money to organisations working in Northern Sri Lanka, Rohingya Muslims and to Kashmiri organisations providing succour in the troubled state. It’s a wonderful gesture of support. Do you think more writers could help out in similar methods? What else can be attempted?

Again, I’m not really sure. I’m not qualified to speak on these things. What I did was merely a gesture of solidarity, nothing more, and I doubt any real relief comes to anyone from it.