National human rights institutions from nine countries to hold meet in Delhi from Monday

The six-day meet is being organised by the National Human right Commission (NHRC) in collaboration with the Ministry of External Affairs (MEA).

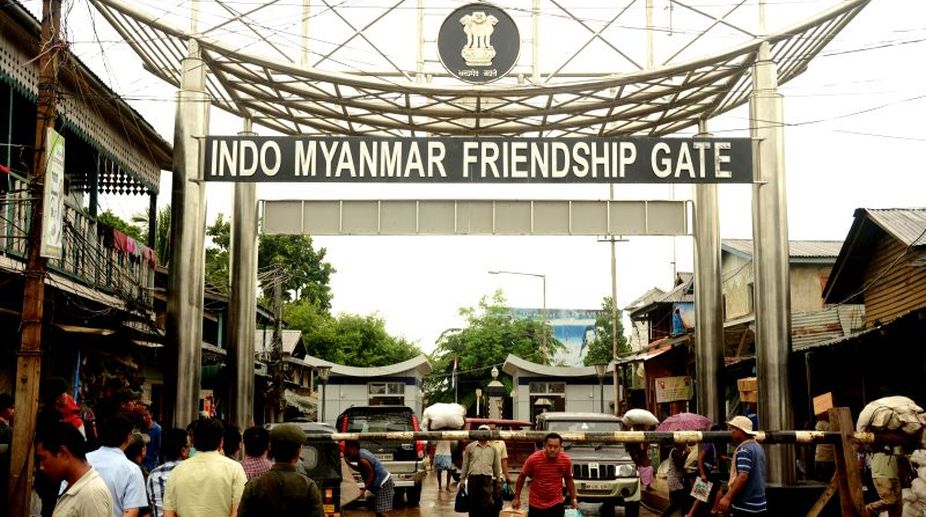

India Myanmar(Photo: Facebook)

When Jairam Ramesh was the Union Minister in charge of the Development of the North East Region, he once commented in a seminar article that the future of the region depended on economic integration with South-east Asia and a political link with India. If one looks at the outcome of the Look East Policy, now Act East Policy, from the regional perspective, the change conceals some sense of despair because nothing much has really taken place so far towards integration of the North-east regional economy with the Association of South East Asian Nations.

No one talks anymore about the ambitious North- East Vision 2020 Document, prepared some years ago by the North Eastern Council. The much-publicised Kaladan Multi-Modal Transport Project, that is supposed to provide the region an access to Sittwe port in Rakhine (Myanmar), has suffered time and cost overruns. Similarly, the progress of the constructions of the TransAsian Highway and Manipur’s railway link from Jiribam to Imphal, is much behind schedule.

Does concentrating on infrastructure alone promote economic integration? The global experience suggests otherwise, as many resource- rich countries, like Nigeria, continued to suffer from development lags even though they were able to develop infrastructure because they were unable to put in place growth- inducing institutions and policies in rural and urban development, health, education, and especially in science and technology and vocational training, essential to promote entrepreneurship.

Advertisement

Consequently, the spin-off from infrastructure growth was limited. In fact, as a general principle, this holds good for all policy initiatives, that is, only the areas endowed with the appropriate institutional and production function could take advantage of any policy initiative. Thus the southern states have been able to forge links with the ASEAN under the Look East Policy since its inception and it will get stronger, now that the ASEAN-India Free trade agreement on services has been operationalised while the share of the North-east in India’s trade with Myanmar remains insignificant. It must be noted that merchandise trade is mainly sea-borne as the cost of transport is cheaper than any other.

Hence the romantic view of the North East/Guwahati becoming the gateway to South-east Asia is a bit unrealistic. This is not possible unless the region’s trade with Myanmar picks up substantially and pre WorldWar II trade links between the Northeast and North and Central Myanmar are revived and strengthened. It would be hard to reach other advanced ASEAN countries because of asymmetries in development between the North-east and those economies. For instance, the per capita GDP of Malaysia is about $10,000 plus and that of Thailand $4,000 plus, meaning highly competitive markets and entry to which will be increasingly difficult due to free trade within the ASEAN and the presence of China, Japan, South Korea and Taiwan and western economies in the Asia Pacific.

The North-east states have diverse perceptions and priorities. The late Purno Sangma once said “For us in Meghalaya the ‘Look East’ begins with look South to Bangladesh.” There is substance in his argument because, Tura, the main town of the Garo Hills, is just four hours’ drive from Dhaka. It takes six hours to Shillong and further four hours to Guwahati from Tura. Indeed, raising trade levels with Myanmar and Bangladesh is the key to economic integration with the ASEAN economy.

Of the two neighbouring countries, the region’s interaction with Myanmar has been problematic due to several constraints. To overcome that a strategic appreciation of Myanmarese economic and political imperatives is necessary for building a North-east- centric “Act Myanmar” policy, essential for success of the Act East policy. Myanmarese scholar,Thant Myint U mentioned in his The River of Lost Footsteps that in ancient times, Arakan was very much an extension of northern India. The word Myanmar means strong horsemen associated with the eighth century multiethnic Nanzhao Empire, which ruled over the Irrawaddy valley and a part of West Yunnan in China. The Nanzhao era created a new life fused with an existing ancient Buddhist culture which led the author to conclude that “from this fusion would result the Burmese people and Burmese culture”.

In the twilight of the Burmese state in 1810- 1826, its power extended to Assam valley, Manipur, Cachar and Jaintia Hills and her defeat in the first Anglo Burmese war in 1824-26 brought Lower Burma and the Northeast under British rule and the entire area was placed under the Bengal Presidency. Again, following the Burmese defeat in the second Anglo Burmese war in 1884, upper Burma too came under the British and a separate province was created with the capital at Rangoon to use Burma, like Assam as “bridgeheads” for extension of British power to Tibet, China and to check extension of French power in Indo China. This “forward policy” led the British to extend its power to the mountain regions — a buffer between China and Burma and inhabited by the tribes who were earlier not under Burmese authority.

The British rule thus pushed the frontier of Burma, as in Assam, to hitherto “unadministered” areas. This was the beginning of the present problem in Kachin, Wa, Chin and Naga-inhabited areas of Myanmar and across the border in Northeast India. And, like in our North-east region, the British divided the frontier tracts of Burma into “excluded and partially-excluded areas”, which covered roughly one third of the geographical area. It placed the tribal inhabited frontier tracts under the direct rule of the governor, away from the political reforms process initiated in the rest of the province. This isolation of tribes provided the theoretical basis of separate tribal identities and, later insurgency, to attain homelands by the Kachin, Mon, Shan and Wa ethnic groups, and even by the Karens in the south as the dualism in administration made separatist ideas feasible.

At present, the leading ethnic groups claim to be “nationalities” and that has not been questioned. The fact of the ethnic armed groups virtually controlling their territories means that the writ of the central government does not run in most of these areas bordering the North-east. Though the situation is more stable on the Indian side as insurgency is more or less under control, there are still problems which recently compelled the Centre to declare Assam as “disturbed”. This has been a major constraint on trade development with Myanmar because it also means trade between disturbed areas of both countries. Of these, the first is the “taxation” imposed by insurgents on trucks operating on both sides of the border and similar levies on traders that act as severe disincentives to export- oriented manufacturing and merchandise trade.

The second is the lack of a dedicated Exim bank for promotion of trade of the North-east region with Myanmar and Bangladesh. The third is lack of complimentarity in economies, which existed prior to 1947. For example, the rice economy of Burma, which produced export surplus of only 1.62 lakh tons in 1855, progressed fast enough to export two million tons in 1906- 7 mainly to meet Indian demands. The assured supply of Burma rice for the tea labour was a major contributing factor to the growth of the tea industry in Assam and North Bengal.

It is this kind of linkage which is missing today. To restore it, more than construction of new roads and rail links, it is necessary to put in place institutions and mechanisms to establish new basis of socio economic inter-dependence and it is naive to plan without stabilising the border areas. As the first step, the “Disturbed Area” tag should go because it produces “unstable stakeholders” on both sides of the border.

Myanmar must renew on fast track the Panglong peace and Reconciliation process by resolving the “nationalities” question while on the Indian side, the Sixth Schedule states, like Meghalaya and Mizoram, may give a serious thought as to the relevance of the Schedule after they attained statehood, as they do not need any further “protection” of tribal rights.

And the restrictive provisions under the Sixth Schedule on land and property ownership act as obstacles to outside investment and Foreign Direct Investment in particular. There is also the need to review the reservation policy in tribal- dominated states, which restricts recruitment of qualified teachers that the region needs to raise the standard of teaching in mathematics and science, critical for creating a technology base and skill development. In all these areas there is scope for developing cooperation with Myanmar.

It’s time now to draw up a “Myanmar first” strategy under a North-east Myanmar Partnership for renewal of the old linkages to unite North East India and Myanmar in their journey to a common economic destiny set by geography, demography, and common civilisational values.

(The writer is a retired IAS officer of the Assam-Meghalaya cadre and has served as a scientific consultant in the office of the principal scientific advisor to the government of India)

Advertisement