Unfinished Agenda

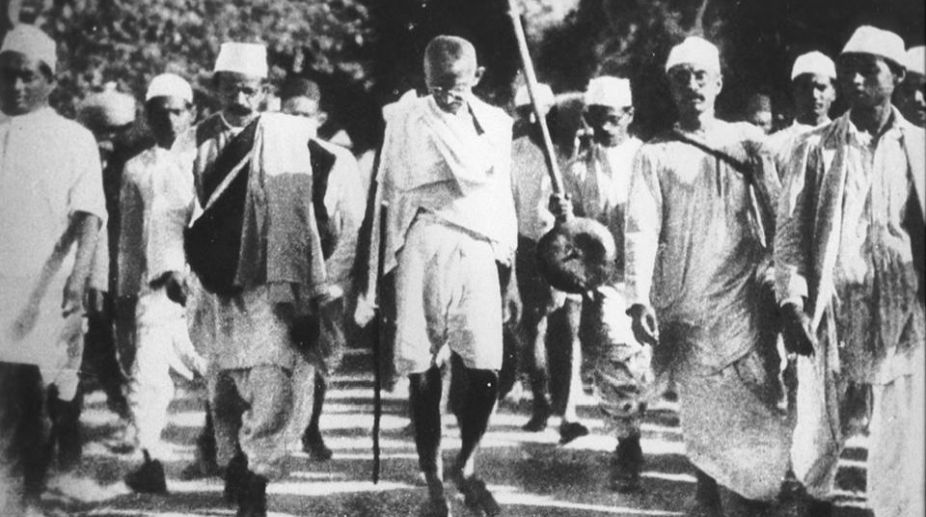

Mahatma Gandhi, the greatest man of the twentieth century, often talked about poverty. For the prophet of non-violence, poverty was the worst form of violence.

(Photo: Facebook)

Lord Linlithgow, as Governor-General, had attributed the failure of the Cripps Mission (March 1942) to the inflexible attitude of the Congress.

In India, there was no consensus on the responsibility for the failure, but the Congress blamed the British government for what it called its hypocrisy, lack of sincerity and for following Machiavellian tactics.

The popular resentment against the Raj intensified as never before. To end the impasse and in view of the general resentment, Mahatma Gandhi wanted swaraj immediately, asserting that British rule had forfeited any claim to legitimacy. In response to the argument that compared to the British, the Japanese were a greater evil, he refused to accept any difference between the two imperialist powers. He dismissed the fear of a Japanese takeover of India.

Advertisement

He was confident that the country would be able to deal with it effectively through nonviolence and by scattering the population in the villages.

Significantly, Gandhi also redefined the role of non-violence in the struggle for freedom. Non-violence, he argued, was the best possible form of political behaviour, but he hastened to argue that violence was preferable to cowardice in the midst of perpetual slavery. Making a fundamental departure from his earlier position, he endorsed violence as a mechanism of defensive struggle. It would not be a negation of non-violence. He could perceive that strict adherence to non-violence was not conducive at a time of unprecedented global conflict, when the demand for swaraj had mass support.

The Quit India resolution, indeed the new Gandhian strategy was in July 1942 placed for approval at the Working Committee meeting of the Congress at Wardha. It resolved that the British should relinquish political power immediately, and this would enable India to play a pivotal role in the war and save the world from the clutches of “Nazism, Fascism, militarism and other forms of imperialism”. But it also emphasised that even after the British departure from India, there would be no disruption in war efforts and more significantly, the British forces would not have to leave immediately.

From the Congress perspective, this proposal was very reasonable and just, but it simultaneously reminded the British that rejection would compel the party to mobilise its accumulated strength of non-violence that it had acquired since 1920, and this would be used to secure swaraj. A meeting of the All India Congress Committee was scheduled to be held in Bombay in early August to approve this new strategy.

The Raj rejected the demand and the Congress was compelled to chalk out its own plank for civil disobedience. On 7 August 1942, the Quit India resolution was accepted, in the face of stiff opposition from the Communists. It remains inexplicable, at a time when Stalin was fighting the war for saving the fatherland, what prompted the Communists to stay aloof from the national upsurge. Nehru moved the resolution and mentioned the fact that the Quit India resolution should not be regarded as a threat, but an olive branch of cooperation.

He also added that “there is clear indication that certain consequences will follow if certain events do not happen”. But Gandhi was more strident and without mincing words remarked: “We shall get our freedom by fighting. It cannot fall from the skies”.

To the question that such a statement violated Gandhi’s own philosophy of non-violence, his reply was that such acts were defensible by the doctrine of self-defence. Gandhi, in defence of his thesis of self defence, also said, “if a man holds me by the neck and wants to drown me, may I not struggle to free myself directly?”

Extending this argument, he asked every single Indian to act freely. But in spite of such militancy, the Mahatma made it clear that the Congress would not act without discussing the matter with the Viceroy. But instead of opening a channel with the Congress, the British started an offensive against the party. This plan to initiate decisive action was decided before the Quit India resolution in June. Immediately after the Bombay meeting, without allowing Gandhi to move forward, all the national leaders of the Congress, including the top brass, Gandhi, Azad, Nehru, Patel and Prasad were arrested (8 August 1942).

The Working Committee of the AICC and the provincial Congress committees ~ except those in the frontier province ~ were declared illegal. The party’s offices were sealed, its funds frozen, and all its publications stopped.

The government justified the action by claiming that the Congress was planning unlawful and violent activities with plans to interrupt communication and public utility services, even to disrupt defence operations, including recruitment. All these charges were baseless and fabricated, but were played up by the British authorities to pre-empt and force the Congress into submission. But subsequent events came as a shock.

The Intelligence network of the Raj overlooked the fact that the Congress had made an elaborate plan of resistance, if its leaders were arrested. The party started recruiting volunteers for civil disobedience and all the provincial committees were instructed to draw up a plan of action. It was stipulated that non-violent methods were to be strictly followed, but with the rider that if Gandhi were to be arrested, the people would be free to use both non-violent and violent means, to counter the violence unleashed by the Government.

The spontaneous outburst surprised both the Government and the Congress leadership. For several weeks in August and September, large-scale violence convulsed several provinces There were extensive protests against the arrest of Congress leaders, pre-eminently Mahatma Gandhi. The police tried to stop such open mass defiance, but the people resorted to stone-pelting, attacks on Europeans, attempts to destroy communication networks and government buildings. The brutal police action, legitimised by the draconian Police Act of 1861, which was enacted to forestall a possible rebellion after 1857, intensified protests.

Attempts at sabotage spread from cities to remote villages. In many places, the British lost total control, however temporarily. The nerve-centre of the revolt was Bihar and the situation became so volatile that the British planned the evacuation of all Europeans from the province.

To bring it under control, military contingents from other areas had to be brought in, and for the first time the Air Force was mobilised to destroy enemy positions. It was only in October that the British administration could re-establish its authority after arresting 27,000 people in Bihar. There were large-scale disturbances in UP and Bombay Presidency as well.

The people’s anger was no less manifest in the Central Provinces, Madras, Bengal, Assam, Orissa and even in the seat of central power, Delhi. Isolated incidents took place in the frontier, Sind and Punjab as well.

(To be concluded)

(The writer is former Professor, Department of Political Science, University of Delhi)

Advertisement