Churchill and Gandhi~I

The maintenance of the British empire was the objective of Sir Winston Churchill (1870-1965) while ending it was the mission of Mahatma Gandhi (1869-1948).

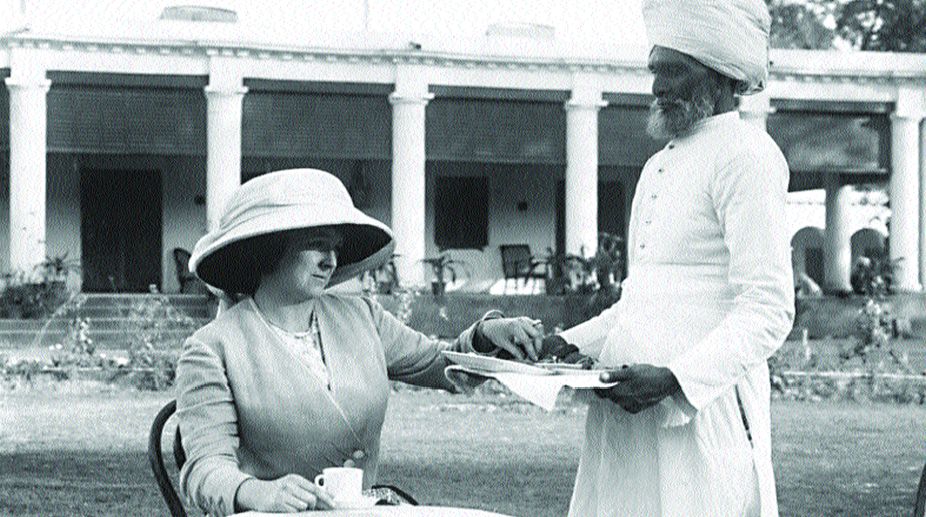

A symbol of colonisation

In an incredible coincidence, two books have been published in recent months, and both have narrated how the British Empire impacted the world with trade, which influenced the economy and culture of England and other nations.

John Williams, a missionary from England, visited Raiatea, in the Society Islands near Tahiti in 1817. He philosophised on the cultural value of drinking tea and how it could enhance the living standards of inhabitants of the islands. He explained that tea may be served in a kettle or teapot. Cups or mugs must be used to pour the tea; a table is necessary and chairs around it for members of the family to be seated on. He said that a table cloth would also be required. This simple practice, thought Williams, brought about a civilised custom to the inhabitants, who were being introduced to tea drinking.

Tea has been one of the most popular commodities in the world. Profits from tea’s production precipitated colonisation and its cultivation introduced changes in countries as labour and market systems were deeply impacted. A Thirst for Empire, written by Erika Rappaport, published this year, takes a profound view of how people through tea’s industry and plantations transformed habits and customs to create our modern consumer society.

Rappaport states that between the 17th and 20th centuries, the boundaries of the tea industry and the British Empire overlapped and this highlights the economic, cultural and political forces that enabled the British Empire to dominate. The author delves into how Europeans adopted and altered Chinese culture to develop a demand for tea in Britain and other global markets, with a plantation-based economy in South Asia and Africa.

Tea was the earliest colonial industry where merchants, tea planters, and retailers used imperial resources to pay for global advertising. Rappaport is a professor of history, at the University of California, Santa Barbara. Her book, A Thirst for Empire, moves from the coffeehouses of London to the humid tea plantations of Assam and advertising firms, revealing technologies and marketing policies that influenced tea’s global popularity. She touches on the average American’s dislike for tea and the involvement of tea planters in South-east Asia, thus unfolding an expressive narrative. Her academic qualities have converted pure information into a vibrant story.

Rappaport addresses the big question, how did tea evolve from an obscure “China drink” to a universal beverage imbued with its many properties? Both miracle of markets and capitalism’s dark underbelly, are, on occasion, evident in tea’s complex saga.

Admiral Lord Mountevans commented that tea drinking worked like magic among soldiers in World War II because it gave courage and attributed that “matey feeling.” It is due to brilliant marketing policies that tea has played a universal role in fostering that “matey feeling,” so desperately sought after, among nations in our volatile world.

On the other hand, Lizzie Collingham has written a narrative also reflecting colonialism and its impact, particularly with England’s dietary habits — The Hungry Empire: How Britain’s Quest for Food Shaped the Modern world. It was published a few months ago and articulates Britain’s food habits, reflecting a world of the past.

Collingham’s book demonstrates that a cup of tea reflects much more than a “cuppa”. A cup of tea in England had the tea leaves from India, the sugar from Jamaica, and the porcelain cup from China; we must not ignore the imported silver teaspoon and lemon — it is a culmination of trade over the last few centuries and illustrates economic change over a period of time.

Each chapter begins with a meal. A 19th century British family in New Zealand is eating meat thrice a day, something they experience for the first time. Even small village shops in 18th century England were stocked with imported cocoa, sugar and Indian calico.

This engaging narrative writes of a “fish day,” on board a ship in the 16th century. Dried and salted cod was a cheap substitute to meat for sailors.

Cod thus prepared lasted “forever”. This recipe was the bedrock of English expansion on those long voyages.

Salted cod then became a delicacy in Spain and Portugal to balance trade in Europe. Sugar shaped the modern era in every corner of the globe and significantly influenced Atlantic Trade. The item

generated vast riches for sugar planters in the West Indies and in turn

benefited the Irish who exported

salted beef and butter.

England’s urban poor ate white bread with wheat grown in the Americas. The poor also consumed sweetened tea rather than calorie-rich beer. The innovation of tinned and packaged foods enabled colonial officers to travel further into remote and distant regions.

The underlying theme of Collingham’s remarkable book highlights a different segment of Britain’s imperial history and the network of trade that held the Empire together.

Advertisement