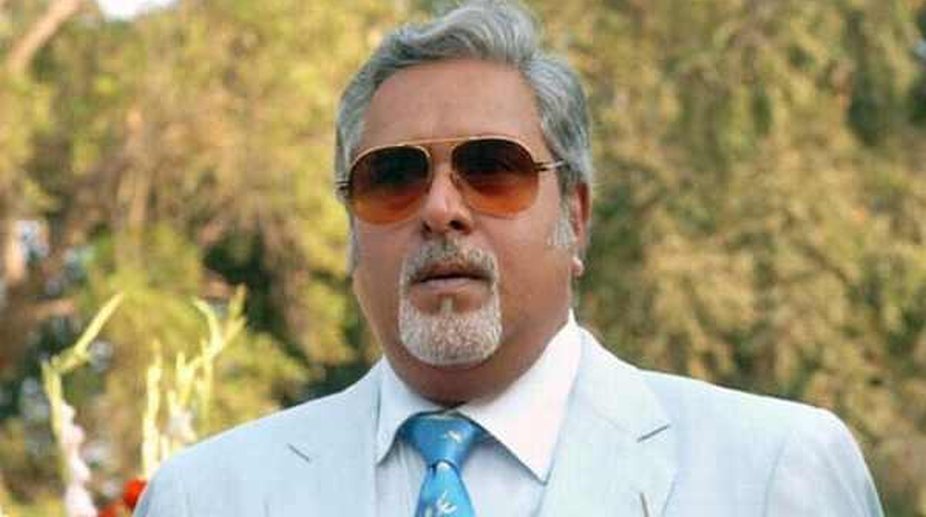

All eyes are now on the 17 May London District Court hearing. Will Vijay Mallya be extradited anytime soon? Speculation is rife. A team of CBI and ED recently camped in London to inform the Crown Prosecution Service (CPS) of UK that the liquor baron siphoned funds from state-owned banks as part of a criminal conspiracy. Question arises: conspiracy with whom? The answer cannot be comforting to either CBI or ED. And will India succeed?

On 18 April, Mallya's arrest and release on bail by the Westminster Magistrates' Court, London, marked the beginning of the extradition proceedings. Subsequently, just a few days ago, the Supreme Court of India held Mallya guilty of contempt of court. Mallya has been asked to be present before the Supreme Court on 10th July. So, Mallya is now surrounded by law with an octopus like grip. Will the law catch up? Will justice prevail ultimately? This question haunts everyone in India. The situation is hazy since the court in UK will have to deal with a cocktail of British and Indian jurisprudence.

Advertisement

Law apart, what has surprised observers is the manner in which Mallya left the shores of India. He swiftly boarded Jet Airways DelhiLondon flight on 2 March 2016. By then, he had left CBI, ED, and 'the Debt Recovery Tribunal (DRT) in the lurch. Now, after 15 months, a consortium of 17 banks in India, is still gasping to recover about Rs 10,000 crore. Mercifully, CBI and ED have now reached London to brief CPS.

After Mallya's departure on 2 March 2016, the government of India waited till 8 February 2017 to hand over a formal extradition request to British High Commission in New Delhi. Why did the government wait for 11 months and 6 days to handover a simple letter of request? This request was promptly certified by the Secretary of State in UK and sent to Westminster Magistrates' Court for further consideration. As a sequel thereto, Mallya was arrested and released on bail with onerous conditions. Arguments on extradition will now commence before the District Court in London on 17 May.

This delay of over 11 months could possibly weigh against extraditing Mallya. Under Section 82 of the British Extradition Act, 2003, passage of time from the date of committing extraditable offence can be a bar to extradition. During the impending proceedings before the Westminster Court, UK's Crown Prosecution Service (CPS) may well have to offer an explanation on behalf of the Indian government, to overcome the hurdle of passage of time under Section 82.

This is not the only hurdle that India may have to encounter to extradite Mallya. British jurisprudence demands exacting standards of procedure and evidence before ordering extradition. The process can also be dilatory. And extradition is a judicial process which takes its own course, in contrast to deportation which is an easier administrative process. Mallya's deportation was declined perhaps because he entered UK with a valid passport.

Interestingly, the process of extradition in UK commences with the Secretary of State, who exercises discretion whether or not to refer the matter to the District Court for consideration. In the instant case, the Secretary of State could well have declined India's request and the matter would then have rested there. But considering the evidence provided by India against Mallya, such a step on the part of Secretary of State would have jeopardised Indo-British relations. India has thus achieved success to this extent so far.

The District Court will now have to deliver a verdict after hearing elaborate arguments and appreciating evidence that is placed before it. The verdict of the District Court would then revert back to the Secretary of State, who is statutorily authorised to take a final view and a decision in the matter. The decision could well be an extradition order. This order would then be subject to appeal before the High Court and the House of Lords. Therefore, a three tier litigation would ensue unless Mallya consents to be extradited, which seems unlikely. So, extradition, if at all, is still a far cry; a high pitched legal battle is in the offing. And the final outcome bristles with uncertainties.

Mallya's woes started in 2012 when Kingfisher Airlines collapsed. Thereafter Mallya's companies defaulted in repaying bank loans. From 2012 till Mallya's fateful departure in March 2016, the state machinery in India proved slack and supine. No action was really visible against Mallya. The fact that Mallya was a member of Parliament could have thwarted any meaningful action. Of course, after Mallya's departure, Government promptly revoked his passport in April, 2016, and accepted his resignation from the Rajya Sabha in May 2016. This was too little, too late. It is against this background that further delay in triggering extradition proceedings by the Indian Government is surprising.

The real issue, however, is not Mallya individually per se, but bank funds that are sinking. Companies, with which Mallya was associated, have defaulted in repaying bank loans hugely. Subjecting Mallya to rule of Indian law is one aspect, but a far more important aspect is to recover bank's dues. The pivotal issue is to restore financial discipline in the banking system in India.

Let's stop enacting/constituting more laws/ordinances, committees/commissions. These actions are barely cosmetic. We need surgical strike of banking industry in India which is going from bad to worse. Just consider this. Banking business as on 31 March 2017 stood at Rs 187 lac crores. India's GDP for 2017/2018 has been projected at Rs 168 lakh crore. These figures highlight the importance of banking sector in India's economic development. A huge chunk of state-owned bank funds have already gone down the drain. The state as the owner is singularly responsible for this situation. The state is also failing to provide adequate capital to banks. This can prove fatal. And involving the regulator (RBI) to statutorily meddle around in bank's recovery of loans is a clear case of conflict of interest. It is surprising why RBI did not protest.

Banking industry in India is the largest instrument for economic development. Government should provide adequate capital to banks, professionalise management, and let RBI regulate without fear or favour. A situation should not be created in which RBI would be blamed in the future for all the failures of the owner of state-owned banks. India's financial security is inextricably linked with health of the banking industry. Lets now recover and punish the loan defaulting corporates who are holding the system to ransom at the cost of the poor bank depositor whose interest earning is being wiped out by inflation and who has now started worrying about the safety of his deposits. Government should wake up to tackle the situation resolutely before it becomes irredeemable.

The writer is ex-Additional Solicitor General of India and a Senior Advocate, Supreme Court of India