Scientists have carried out a successful head transplant on rats ahead of plans to attempt a similar operation on a human later this year.

During the procedure, the head of a smaller rat was attached to the body of a larger rodent. Rather than simply replacing the head, the team attached the donor head to the body of the larger rat, creating an animal with two heads.

Advertisement

The operation involved three rats in total — the donor, the recipient and a third used to maintain the blood supply to the transplanted head.

A pump was used to transfer blood from the third rat to the donor head in order to ensure the brain was not starved of oxygen. After the procedure, the rat whose head had been transplanted was able to see and feel pain, showing the brain was functioning despite having been detached from its original body.

The experiment, reported in the journal CNS Neuroscience and Therapeutics, was designed to investigate issues relating to blood flow to the brain and the possibility of the immune system rejecting the new organ — problems that could arise during a human transplant.

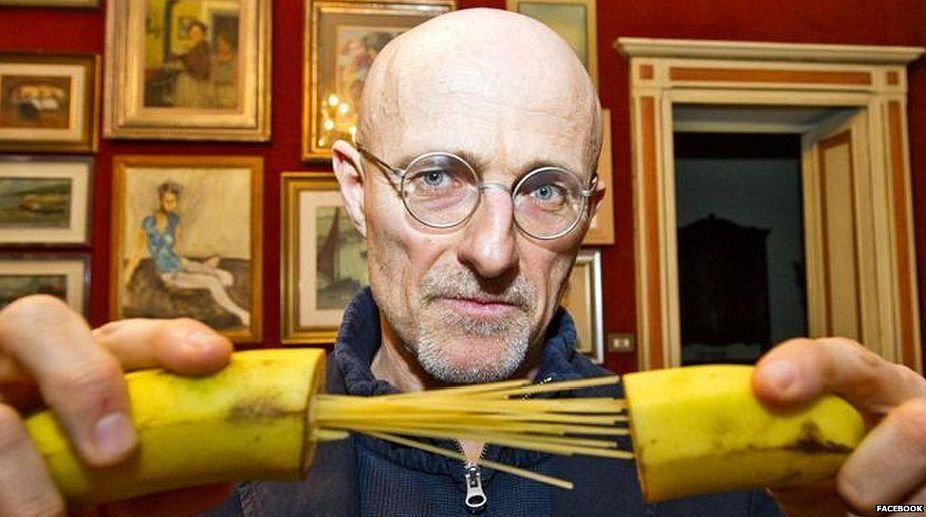

The procedure was carried out by a team including Sergio Canavero, the controversial Italian neurosurgeon who has pledged to carry out a human head transplant by the end of 2017. Canavero had previously announced that his patient would be Valery Spridonov, a Russian man who suffers from the degenerative muscular condition Werdnig-Hoffman’s disease, but the doctor has since said it is actually likely to be an, as yet unselected, Chinese person. The reasons for the change are unclear.

The neurosurgeon and his collaborator, Xiaoping Ren from the Harbin Medical University in China, have between them previously carried out a series of experiments involving head transplants. Their method involves using a very sharp knife to cut the spinal cord and then placing the body in a state of hypothermia to allow it to heal.

In one, they claimed to have severed 90 per cent of a dog’s spinal cord before re-attaching it. In another, a head transplant was reportedly carried out on a monkey, and a third experiment saw the spinal cords of mice being cut and then reattached in such a way that the animals were able to recover their ability to move.

The pair also claims to have experimented with human head transplants using dead bodies. None of the experiments were peer reviewed and Canavero has a number of critics in the scientific community who accuse him of sensationalism.

His latest studies have been announced via press releases before they were published in the journals to which they had been submitted. The editor of one of the journals, Surgery, said that significant work was needed on the draft paper before it could be published.

Other experts say there is not sufficient evidence that a human head transplant would work. Hunt Batjer, the president elect of the American Association for Neurological Surgeons, has criticised Canavero’s plans to transplant a human head.

“I would not wish this on anyone,” he said. “I would not allow anyone to do it to me as there are a lot of things worse than death.”

The Independent