When Piketty came to India

Thomas Piketty, the French economist and author of the famous book Capital in the Twenty First Century, was recently in India. He delivered a lecture on the state of inequality globally as well as in India.

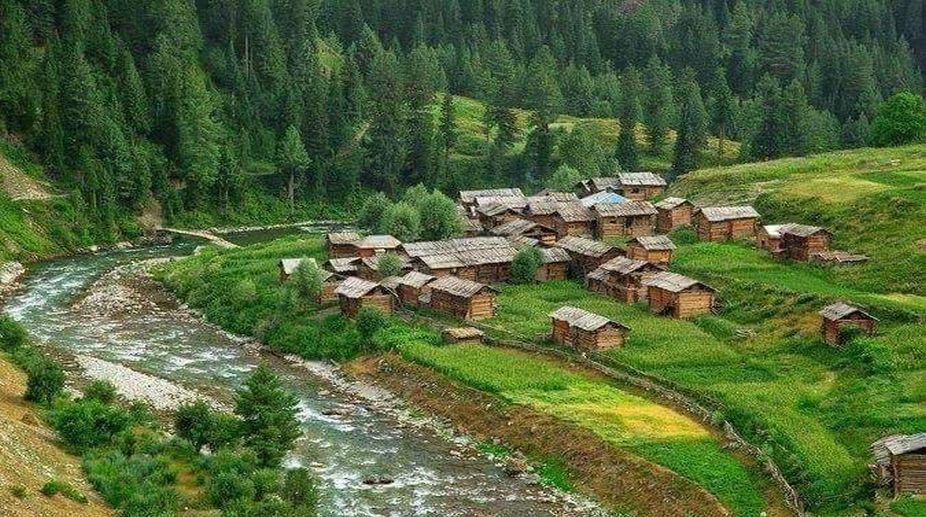

Representational Image (PHOTO: TWITTER)

The decision in Islamabad to alter the status of Gilgit-Baltistan in POK and describe it as a province rather than a region has not been well received in India. The Pakistani decision may be of little practical significance, for POK has never had any autonomy worth the name and the latest move is unlikely to make any real difference, but to come up with this changed nomenclature acts as a reminder of unresolved issues and of the illegal occupation of POK by Pakistan. Indo-Pak differences over J&K have been especially prominent lately on account of the newly developed CPEC (China Pakistan Economic Corridor) along an alignment that traverses a portion of POK, and has been denounced on that account by India as a further infringement of its sovereignty. Chinese complicity in Pakistan’s actions in POK is a long-standing Indian grievance and it has added a further dimension to the unresolved issues between them.

Much of what divides India and Pakistan in J&K goes back right to the beginning, when India and Pakistan emerged as independent nations. The complication of the Chinese connection was not part of the initial set of issues but it has progressively become more substantial as Sino-Pak activity in the mountains has taken on a more challenging aspect. As a means of thwarting India and pursuing its own territorial ambitions, Pakistan has actively tried to draw China into a role in Indo-Pak affairs in J&K, most notably by making extensive territorial concessions in the Shaksgam border region where a Sino-Pak border agreement in 1963 handed over large territories to China. The agreement has no validity so far as India is concerned, encroaching as it does on land that is rightly part of India, but since the agreement was concluded the collaboration between the two signatories has developed steadily. From early days China collaborated with Pakistan in developing road access from Xinjiang to POK in order to encourage trading activity between the two regions. This route came to be known as the Karakoram Highway (KKH) and it was largely made possible as a result of Chinese financial and technical assistance, with much of the required labour force being provided by that country.

Advertisement

Since then the pattern has been repeated and Chinese support has been provided for major infrastructure schemes in the mountain region. The KKH has become an active road link and permits a certain amount of trade though there are obvious limitations owing to the difficulties of the terrain. Even so, Pakistani traders make regular journeys along this route and fairly brisk commercial traffic has been established. Apparently some manufacturers of a particular sort of silk cloth in Shanghai that had been popular in South Asia more than a century ago have seen the opportunity and have revived a modest amount of manufacturing of this item specifically for the Pakistani market; they would no doubt look to the more appealing Indian market if the opportunity presented itself. At present, the KKH can be regarded as a small tributary of the Silk Road now being revived by China but if circumstances were to change it could amount to something more. It should also be seen as a precursor of the more ambitious CPEC which seems to follow much the same access route.

Advertisement

These activities in the surrounding area have required watchful response from India and alert awareness of the new developments. The paramount concern for India is to ensure that its sovereign rights are maintained at a time of change and of enlarged international activity all around, and at the same time to provide adequate developmental input for the benefit of the people of the region. The development issue requires a measure of cooperation between the sundered parts of J&K and is vulnerable to terrorist activity, but extensive negotiations have taken place in recent years to look for a modicum of cross-LOC exchanges to meet demands from the local population. As a result, some steps have been agreed that have done something to ease the situation for people around the LOC ~ among steps agreed between the sides, opening road links has been a big success, and though there have been frequent setbacks, the process continues, to the benefit of the locals.

As a result, there is considerable sentiment in J&K in favour of increasing the cross-LOC travel routes, facilitating people-to-people contact and expanding commercial exchanges. Revival of the old caravan routes based on Kargil where historic lines of commerce once met is a frequent demand; this particular proposal has been held up owing to the unfavourable response of the Pak military authorities who would not wish to see easier access leading perhaps to the nearby KKH which, in the military mind, is a strategic lifeline between Pakistan and China. Such sentiments have held up the improvement in exchanges that was being attempted earlier, for even at times of greatest estrangement the effort to maintain a certain amount of cooperation has never been abandoned. Dr Manmohan Singh’s government was especially successful in conducting a back-channel dialogue that affirmed the essential legal and other principles of India’s policy while permitting a certain amount of interaction across the line. This diplomatic effort did not eventually lead to the results that at one time seemed attainable but it has left a body of useful ideas that could come into play when circumstances permit and dialogue can be resumed.

At present, relations are in a trough and the issue of state-backed terrorism has overshadowed all else. Mr Modi has made more than one striking gesture of outreach to demonstrate his willingness to ameliorate relations but each time his intentions have been thwarted by incidents that have made it impossible to proceed further. The CPEC has added a

further level of disagreement by bringing differences between India and China into consideration and thereby reducing further the chances of improvement in India-Pakistan ties. There can be little early expectation of change for the better.

In these circumstances, J&K’s Chief Minister Mahbooba Mufti has shown boldness in coming out with the

suggestion that, far from opposing CPEC, India should consider joining it. Chinese spokespersons have on various occasions invited India to join but India has kept aloof, considering as it does that CPEC encroaches on its sovereignty. Ms Mufti’s views reflect the specific interests of her State which has much to gain from the opportunities that could flow from CPEC, including commercial and people-to-people contact, and revival of movement between Ladakh and Baltistan. What she says may not be immediately practicable but it merits serious consideration. India’s long-term interest is in improvement of ties with the neighbour and to find ways of transcending their differences and mutual hostility.

The writer is India’s former Foreign Secretary.

Advertisement