Kareena and Shahid Kapoor’s rare reunion sends fans into a ‘Jab We Met’ frenzy

Kareena Kapoor and Shahid Kapoor reunite at their kids' school event, sparking 'Jab We Met' nostalgia among fans. Details inside.

For a long time, the world had conveniently divided Indian cinema between Satyajit Ray and Bollywood. That there was nothing in between as was evident from Penelope Houston’s famous observation that as long as someone didn’t come along to make a difference, “Ray’s Bengal will be cinema’s India”. That was around the time creative young minds from across the country were discovering the art of cinema not just in the work of Ray but in the films of global masters like Bergman, Kurosawa, Fellini, de Sica, Wajda and critics who went on to produce the French New Wave. The discovery reinforced the film society movement that Ray had begun in the 1940s and later found young enthusiasts like Adoor Gopalakrishnan studying direction and screenplay writing at the Pune film institute and then masterminding the emergence of the Chitralekha Film Society in Kerala. If the idea was to pave the way for a new kind of cinema literacy, there was no personal ambition till then to move from theatre, to which many of them were still attached, to an industry that posed many hurdles in India.

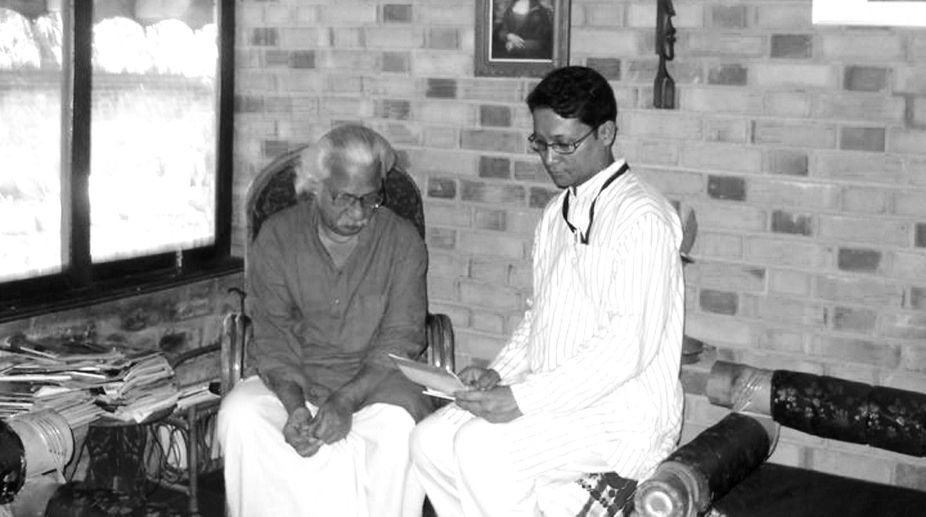

But the change had to come in the global response to Indian cinema. Adoor Gopalakrishnan may well claim to have destroyed some firm impressions when he emerged with a remarkable cinematic vocabulary in Swayamvaram in 1972. Parthajit Baruah’s book is the latest in a series of studies on the work of Kerala’s most well-known filmmaker. Clearly he was never part of the popular scenario in his state.

Advertisement

But with quotes from foreign critics like Jean-Michel Frodon from France and Derek Malcolm from Britain as well as from senior contemporaries like Shyam Benegal, the author defines the credentials of a filmmaker who was justly regarded as the heir to Satyajit Ray in the eyes of world cinema. Derek Malcolm is quoted as saying, “His films come from as deep within the culture of Kerala as Ray’s came from within Bengal. But, like Ray, his work easily transcends those boundaries”. This is confirmed by the countless festivals and awards even though he may have just made around a dozen films that have found limited space in theatres. Malcolm goes on to note that Adoor “is as strict with himself as Ray, refusing any compromise for the sake of popularity and his films not only have an acute sensibility but a force of expression that underlines the nature of what he wants to say’’. Gopalakrishnan himself has often acknowledged his debt to Ray in terms of the human appeal that runs through his work. But within that broad canvas, there are differences between the two that the author is quick to notice. While Ray was a great storyteller and delved into the wealth of Bengali literature — from Tagore to the modern writers with original screenplays as well — his younger contemporary in Kerala was not so keen on plot-driven material. His films are more cerebral, complex and metaphorical with long passages of silence. Ordinary people and everyday occurrences contribute to the larger picture of Kerala’s socio-economic realities and become an integral part of an artistic idiom.

Advertisement

If Ray’s characters are outspoken and the situations come alive with brilliant exchanges that can never really be translated into another language even in another part of India, Gopalakrishnan’s protagonists have a world within themselves that he loves to explore. In the process, he has never compromised with the principles of pure cinema and never really began to make films till he was ready to follow his artistic conscience. These are facets of his work that the author reveals in his study though much of it is carried over from earlier studies.

There is a chapter that deals at great length on the socio-political climate in Kerala that formed the backdrop of films like Kodiyettam and Mukhamukham. There are also efforts to depict a conscious effort to break away from typical images of Indian women in Swayamvaram, Elippathayam and Mathilukal where the characters represent the struggle of women to survive in a conservative society. But his women are never rebels. They are strong but cannot escape the compulsions of a male-dominated society. The author ascribes this to the debt that Gopalakrishnan owed to his mother just as he relates the non-violence of his male protagonists, even when they are confronted by injustice, to his firm attachment to Gandhian principles.

While all this gives the filmmaker the position he deserves in Malayalam cinema, the book seems to miss out on the broader canvas of Indian cinema. The Indian New Wave, when it did make an appearance, was more of a concept than a constructive movement. Baruah may have reasons to consider Gopalakrishnan as the most prominent ambassador of the generation that slipped into the parallel stream though it was Mrinal Sen who made Bhuvan Shome on a ridiculously low budget provided by the Film Finance Corporation and tasted what he had described as an “unexpected” success. Adoor himself never reached out to the FFC that began to support the new generation of filmmakers. The more pertinent question was what the “new wave” was all about apart from the fact that they were all in search of an “alternative” idiom that never really reached audiences and, if they did, produced a climate of confusion. And, finally, it never lasted long enough to challenge the powers of the establishment.

Baruah offers only a sketchy part of the history perhaps partly because Gopalakrishnan never really considered himself to be a segment of that alternative movement. Instead, he confronted political complexities in his own style as he did in Kathapurushan that offered a broad sweep of the socio-political changes from the 1940s that marked the period of the filmmaker’s childhood to the turbulent decades that followed. The pamphleteering that marked the protest of many of his contemporaries was replaced by the multiple realities, moral ambiguities and the introverted types that he turned into lasting images.

The author returns to the films to have a new look but, for those who have been following Gopalakrishnan’s work over the years, there would not be too many new insights.

Students of cinema or research scholars may still find enough material to make this study a worthwhile document. The author rightly recalls Swayamvaram as not just being a turning point in Malayalam film history in terms of themes and cinematic ideas like the use of sound effects but also as a social and artistic experience that can be further explored. Gopalakrishnan remains a master craftsman speaking with courage and subtlety in the language of cinema. This book could turn out to be a well-documented reference.

The reviewer is Director, The Statesman print Journalism school

Advertisement