Walking down the streets in Edogawa Ward, Tokyo, I came across a number of Indian families and inhaled the inviting aroma of spices from Indian restaurants.

According to the Edogawa Ward Office, there were 3,758 Indians living in the ward as of January this year, the most of any municipality in the nation. That means about 30 percent of the Indian people in Tokyo, as well as 10 percent of those in the entire nation, are concentrated in Edogawa Ward. Why is that?

Exhibiting culture

“This is so light and airy. I feel like I’ve become Indian,” said a female high school student who was among those trying on colorful sari at the Edoga-World Festival 2018 in the ward on March 25.

Geetu helped them put on the traditional clothing. “Saris are familiar outfits for Indian women. I’m glad that our culture is known by girls in Edogawa Ward,” said Geetu, who runs an Indian grocery store in the ward.

The event booth that she was manning was set up by the Indian Community of Edogawa, an Indian mutual aid society. The booth exhibited black tea leaves and sitar musical instruments, with the music of traditional Indian dance playing in the background.

Community Chairman Jagmohan Chandrani, 65, said with a smile, “Many Indians fit in with the local community and live their lives there.”

Chandrani’s family has operated a trade business for generations. He came to Japan by himself in 1978 and began living in the ward’s Nishikasai area, where he has a storehouse to keep imported black tea leaves from India.

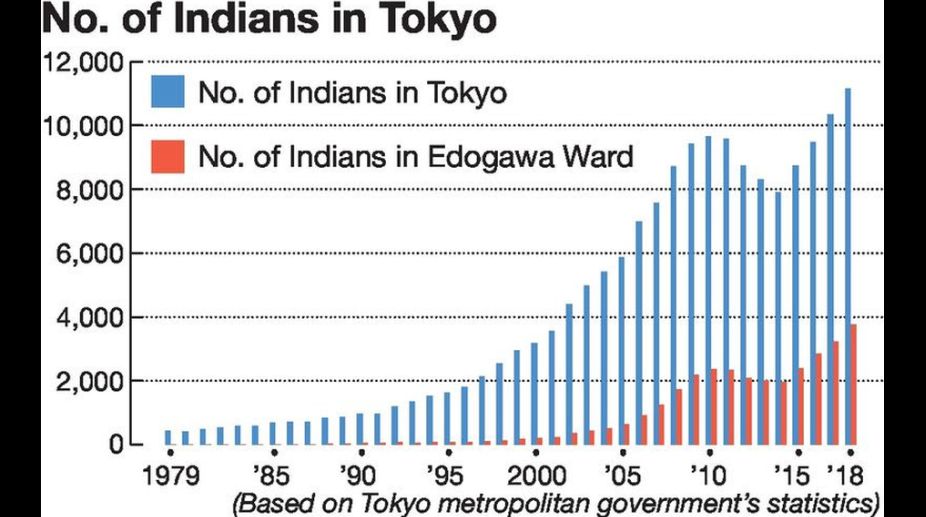

According to Tokyo metropolitan government statistics, there were 440 Indians living in Tokyo in 1979, a number that increased to 11,153 in 2018. Among them, more than 30 percent live in Edogawa Ward — mainly in the Nishikasai area.

Millennium glitch

One catalyst for so many Indians coming to Japan was the “Y2K problem.” Numerous Indian engineers who excelled at information technology were invited by Japanese companies to come and live in the capital.

The Japan-India Global Partnership that was signed in August 2000 between Japan and India also supported this move. According to the Foreign Ministry, the duration of the working visa for IT engineers from India was expanded from one year to three years.

So why was Nishikasai chosen as their home ground?

“The Tokyo Metro Tozai Line connects the area with the Otemachi and Nihonbashi districts, where leading companies are concentrated. It’s a convenient location,” Chandrani said.

However, it’s said that local real estate agents were reluctant to rent homes to Indians at first. Chandrani, who was already known as a mentor for Indians in Japan, scrambled to negotiate with local rental businesses, saying things like: “This person has a decent job and income. Please let them rent a home.”

The northern side of Nishikasai Station began to be crowded with northern Indian restaurants, while the southern area was home to southern Indian restaurants. Nishikasai has gradually become a place where Indians can enjoy the taste of their homeland.

An event reproducing India’s traditional Diwali festival has been held since 2000, and schools for Indians have also been established in the ward. In 2006, the Global Indian International School Tokyo opened, providing education for children from nursery school through the third year of high school. At first it had around 50 students, but now it has about 650. Classes are all given in English, and these days about 40 percent of the students are Japanese.

Principal Rajeswary Sambathrajan said she was surprised there are so many Japanese applicants, and expressed hope for raising globally-minded people from Edogawa Ward who will go out into the world.

“I’ve found myself living in Nishikasai for almost 40 years, which is longer than the time I’ve spent in my home county,” Chandrani said. “Nishikasai has been an emerging area and almost free of local constraints. It is probably another reason this area has accepted foreign culture.”

His said favorite place is the Arakawa riverbank, as the flow of the grandiose river reminds him of the Ganges River in his home country.

(The Yomiuri Shimbun)