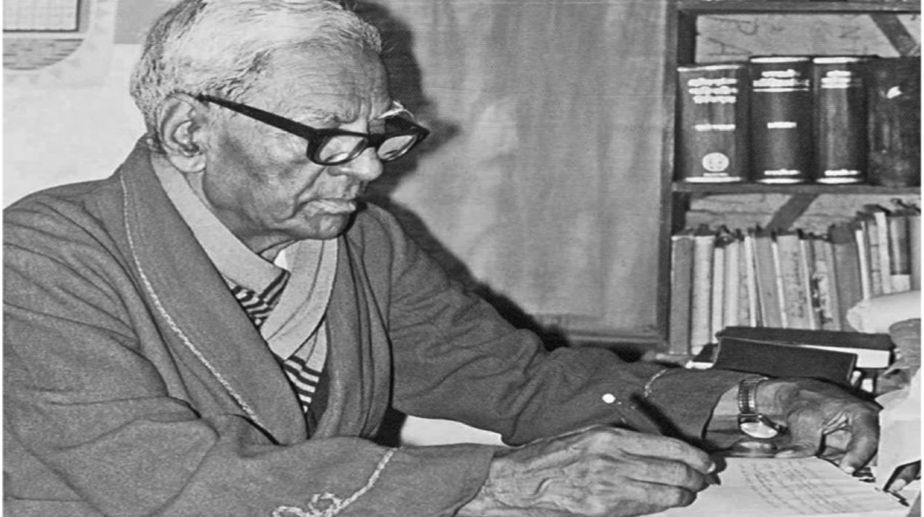

It was in a most turbulent period of the history of Bengal that Abul Mansur Ahmed fought hard against social prejudice and religious bigotry. His brilliance in various fields, be it politics, journalism or literature, made him a popular name in undivided Bengal. He was a superb satirist, a thoughtprovoking essayist and an astute political commentator.

Ahmed witnessed and contributed to the rise of political and cultural consciousness in Bengali Muslims. In his youth, he participated in different social and cultural movements and in his more mature years, he blossomed as a writer, journalist, politician and, most importantly, as a social thinker. Ahmed (1898-1979) was a keen observer of his contemporary world, which he saw with the eye of an artist, who portrayed life not only as it is but also as it could be. The many different roles he played made him an exceptional writer, experienced politician and an ace journalist. But it is in the capacity of a litterateur that Ahmed shines still today and will do so in future.

His youngest son and editor of The Daily Star, Mahfuz Anam, described as follows the moment of his father’s birth, “Abul Mansur Ahmed was born in the Farazi family when the muezzin was calling for Fazr prayers on Saturday, 3 September 1898. His mother suffered severe pain for several days before the boy was born. After the birth the midwife declared that the boy was stillborn.

Ahmed’s maternal grandfather Meherullah Faraizi was a prominent figure in the non-communal anti-British Faraizi movement. Being informed about the daughter’s prolonged delivery pains he came to see her and was informed about the stillborn baby. Deeply saddened, he wanted to see the child who was wrapped in banana leaves and left outside the hut. Emotionally shattered, the grandfather’s heart drew him to pick up the baby to kiss him. To his amazement he saw the ‘dead baby’ flicker his eyes and thus Abul Mansur was born a ‘second time’.”

Emeritus Professor Anisuzzaman, said, “Parashuram said many things about Hindu deities but the Hindu community tolerated that; Abul Mansur Ahmed’s contemporary society tolerated him too. I have doubts whether any editor now would dare to print such stories and society would tolerate him. The target of Abul Mansur Ahmed’s attack was not any individual, a community or any particular religion. He revolted against prejudice and superstition in general. Even 80 years after the publication of Aina, there is still a need for such a book.”

After completing his studies in Mymensingh and Dhaka, he went to Calcutta (now Kolkata) for further studies and to follow his dream of writing. He worked in many weekly and daily newspapers and wrote his famous satires during this period. He became involved in anti-British movements, was inspired by Netaji Subhas Chandra Bose, and worked under Sher-e-Bangla AK Fazlul Huq and Huseyn Shahid Suhrawardy. Ahmed started with the Swaraj Party led by Deshbandhu Chittaranjan Das and joined Congress, attracted by the leadership of Subhas Chandra Bose. He played a significant role in the Krishak Praja Party. He was a member of Indian National Congress, Krishak Praja Party of Fazlul Huq and later joined the Pakistan Movement. In 1946, he founded and edited Dainik Ittehad from Calcutta, which was to become one of the fastest growing newspapers of the time.

Through Ahmed’s satires, he struggled against all forms of bigotry and exploitation in the name of religion and political hypocrisy. In the early 1940s, when the demand for Pakistan was gathering support, Ahmed foresaw the issue and wrote that the state language of East Pakistan must be Bangla.

After the Partition, Ahmed returned to his native Mymensingh, restarted his law practice and continued his political activities. He was one of the early leaders of the Awami League and the principal author of the famous Ekush Dafa, the election manifesto of Jukta Front (United Front) in 1954, which routed the Muslim League from East Bengal politics. He later became the education minister in Sher-e-Bangla’s short-lived government. In 1956, he became the commerce and industries minister in the central government of Pakistan, headed by Husyen Shahid Suhrawardy as the Prime Minister. He used to be named the acting Prime Minister of Pakistan during Suhrawardy’s foreign trips.

Ahmed was imprisoned, along with many leaders of East Bengal including Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, when martial law was promulgated by General Ayub Khan in 1958. He was released in 1963 after which he practically retired from politics and devoted himself to writing.

Among his books are his political and personal autobiography, Amar Dekha Rajnitir Panchash Bachhar and Atmakatha, his satires, Aina,Food Conference,Guilliverer Safarnama, his books of essays, Sher-e-Bangla theke Bangabandhu and many others.

Of all his work, Ahmed is most remembered as a satirist. He chose satire as his main genre in literature but he also wrote several novels depicting social injustice.Each of his satires is timetested. Among them, Aina is most noteworthy. InAinar Frame, the foreword to Aina, poet Kazi Nazrul Islam wrote, “Normal mirrors reflect the outward picture of a man. But the Aina my friend Abul Mansur Ahmed has created has caught the inner picture of man. People who roam around us wearing various masks have had their real face revealed in Abul Mansur’s Aina. We met them all the time in temples, mosques, on the dais making public speeches, and also in the literary arena.”

Ahamd’s other humour pieces like Hujur Kebla and Nayebe Nabi are also unparalleled in Bangla literature. He showed his intellectual courage by writing these books in the 1930s and 1940s while contemporary writers were cowed down by fundamentalists.What Ahmed wrote at that time about religious bigotry one cannot think of writing in the 21st century.

In his typical satirical style Ahmed had this to say about the role of an editor. “To write editorials, editors have to be a scholar in all subjects. They are selfassigned advisor to all in all matters.They advise Mr Jinnah about politics, Gandhiji about non-violence, Acharya Prafulla Chandra about chemistry, Dr Ansari about medical science, Huq Shaheb (AK Fazlul Huq) about running the government, Shaheed Saheb (Huseyn Shaheed Suhrawardy) about party politics, Maulana Azad about religion, even General de Gualle about war policy and Stalin about communism. Giving advice is their responsibility and duty. That is why they are editors.”

As a visionary and an intellectual, Ahmed was far ahead of his time. Imbued with patriotism, he stood against corruption all his life. He used his mighty pen against all inconsistencies in society. His belief in democracy was life-long and unshakeable. For him it was the best form of government and he wrote relentlessly to build a democratic society.

In his writings, Ahmed was vocal against a backward, negative outlook towards life. He observed life from close quarters. He adopted satire as a medium to serve his people as he observed the plight of Bengalis in general and of the Bengali Muslim community in particular. With his keen sense of observation he also saw the hypocrisy of the people in the guise of so-called patriotism.

Rabindranath Tagore had written, “Baire jobe hashir chhata,bhitore thake ankhir jol (On the outer side is a ripple of laughter, inside drops of tears)”. This also applies to the literary works of Abul Mansur Ahmed. As Shilpacharya Zainul Abedin drew a sketch of the famine, Ahmed drew a sketch of social evils in his works. And he succeeded in unmasking those responsible for the famine and the distress of humanity.

In Bangla literature, Abul Mansur Ahmed remains an important figure. Society is not yet free from the social, political, religious and cultural vices against which he wrote so vigorously. Use of religion in politics, the influence of the pirfakirs in social life and the hypocrisy in the name of politics still persists. But today, no one is as vocal against these as Ahmed had been. We now need such writers and thinkers more than ever before.

The daily star/ann