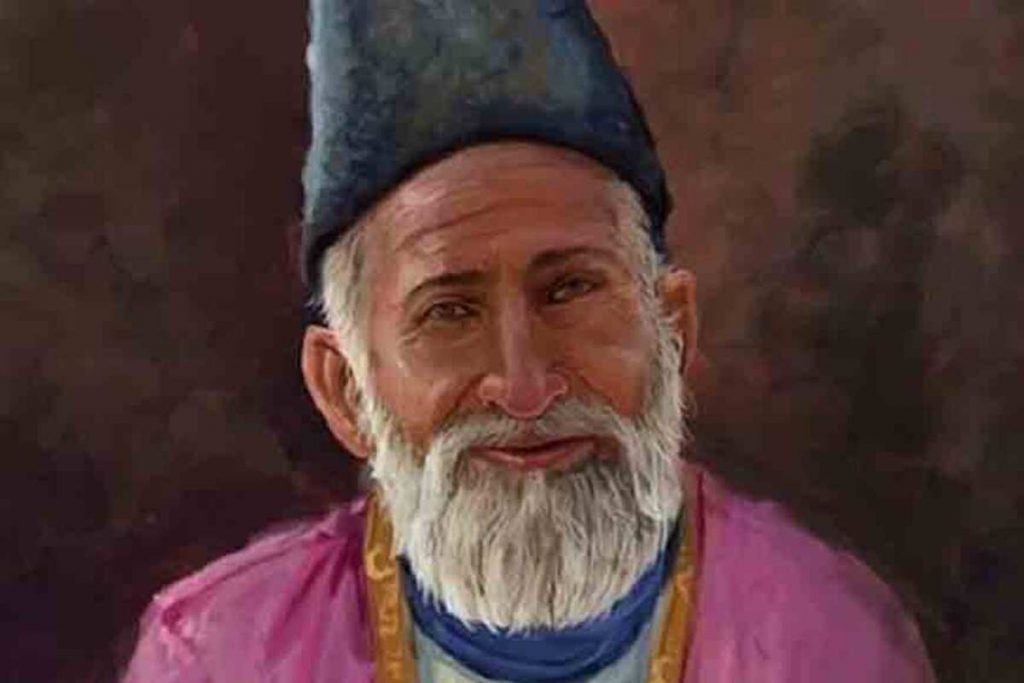

Did a city during colonial rule and times of peril offer everything except a remedy for death? Yes, the city was Kolkata, and the answer, a definite yes, was provided by one of India’s greatest exponents of creative dexterity and cerebral power, Mirza Asadullah Khan Ghalib (1797-1869). He termed it a city of bliss well before Dominique Lapierre’s much-talked-about sobriquet “City of Joy” (1985) gained currency.

Born in Agra and having spent a fulfilling literary life spanning more than a half-century in the culturally resplendent capital of the Mughal empire, Delhi (in his poetic idiom, the city was a paradise on earth or soul of the world), Ghalib arrived in Kolkata after an arduous journey lasting over nearly two months to seek redressal of his long-drawn pension case from the British government.

Ghalib stayed here for eighteen months (1828-1829). Kolkata’s cultural vibrancy, literary sensibility and cosmic vision had cast a spell on him, and he remembered the city all along. For him, merely mentioning the name of Kolkata would bring a shaft that pierced through his heart (“Kolkata ka jo zikr kiya tu ne hamnasheen, Ek teer mere Seeney mein mara key haye haye“). An unprecedented sync up of culture, spirituality, metaphysics, music, art, literature, dance, a quest for modern knowledge, adoption and remodelling of life retaining the essential cultural ethos left narcissist Ghalib awe-struck. He wrote to Mirza Ali Baksh Khan:

“Calcutta is remarkable! It is a world where everything except a remedy for death is available. Every task is easy for its talented people. Its markets have an abundance of everything except the commodity of good fortune. My house is in Shimla Bazaar. I was easily able to find a house within a day or two of arriving here. In short, it is God’s grace that a careless one like me, who had awakened from a deep sleep, and who went to the durbar without washing his face, was given a place in the heart of the rulers and awarded a position higher than I expected in the assemblies. I was blessed with a kindhearted mentor, a member of the council, Mr Andrew Sterling, who is willing to listen to the pleas of this brokenhearted one and put healing ointment on his wound”. (Meher Afshan Farooqui produced the translation of the letter in her book Ghalib: A wilderness at my doorstep, Penguin, Random House, 2021).

The honeyed adulation of some high-ranking British officers makes Ghalib’s streak of servility explicit, but it was more than a pretty speech. Ghalib witnessed the educational and technological advancement – astonishingly motorised ships, firearms, and well-oiled bureaucracy at Calcutta, which almost altered his worldview. Realising the effervescence of possibilities that the new world offered, Ghalib virtually castigated Sir Syed (1817-1898) for editing a historical text of the 16th century, “Aine Akbari” (administration of Akbar), produced by a well-known scholar of Akbar’s court Abul Fazal. Sir Syed requested Ghalib to write a foreword (taqriz) for it. Ghalib did oblige by writing a short Persian poem, but its vitriolic tone dashed Sir Syed’s hope. Instead of appreciating the compiler’s painstaking effort and research acumen, Ghalib saw no merit in the book. It has no relevance today and regretted that Sir Syed spent too much time on something that is an exercise of futility. He heaped praise on the British, who knew all the methods of governance that the world witnessed.

Ghalib’s visit to Kolkata can be reckoned as a voyage to modernism, cultural plurality, and new poetic sensibilities. The effervescence of possibilities that Kolkata offered left an indelible mark on Ghalib. Several eminent scholars, such as Qazi Abdul Wadood, Malik Ram, Ehtisham Hussain Khaleeq Anjum, and Haneef Naqvi, diligently spelt out how Ghalib responded to the new world that had the potential to subvert his literary assumptions and poetic convictions. During his stay, Ghalib sifted through his poetic works and made a judicious selection of Urdu Ghazal that appeared later, and his widespread popularity rests on it. Malik Ram mentioned that Ghalib composed more than a hundred ghazals here. Since several Persian-speaking Iranians and residents of Central Asian countries thronged the city, Ghalib got the opportunity to interact with them, and it helped him hone his Persian. It also prompted him to compose poetry in Persian more.

One also tends to agree with Meher Afshan Farooqui (2021), who asserted that the literary ambience of the city overwhelmed Ghalib as literary gatherings here offer a greater openness with more freedom to disagree. Ghalib had a stopover in Benaras on his way to Kolkata. On reaching the city, Ghalib produced two long poems (Masnavi). He was the first Urdu poet who evocatively depicted the multi-layered allure of Banaras in his poem Chiragh-e-dayer (Lamp of the temple) and Baad-e-Mukhalif (adverse wind), in which Ghalib showed how one could fashion the gripping narrative drawing on the language of abuse to teach a lesson to his petty adversaries. Did Kolkata impel Ghalib to adopt a new poetic idiom? This question is hardly explicitly answered by critics. However, Professor Qazi Jamal tried to find the answer using the close reading method, and his answer was a definite no. Ghalib evocatively rendered what he saw in Kolkata in one of his famous ghazals, “Woh baada-e-Shabana ki sarmastiyan Kahan/ Uthiye ki bus ab lazzat-e-khwab-e saher gaiye (Spirited days and nights intoxication no longer exist! Get up the pleasure of sleep of dawns melted away).

After Ghalib, it was the turn of another luminary of Urdu prose, Sir Syed, to explore the cultural vivacity and administrative resilience at Kolkata. As a member of the Vice Regal Legislative Council (two terms), he visited the city time and again. He developed a personal affinity with Surendernath Banerji, and his multilingual newspaper, The Aligarh Institute Gazette, wrote an editorial on him when he visited Aligarh in 1884. Sir Syed was greatly influenced by the public intellectuals and social reformers of the 19th century India, such as Raja Ram Mohan Roy, Ishwarchand Vidyasagar, Debendernath Tagore, and Keshab Chandra Sen, and he wrote their obituaries that appeared in his periodical.

Ghalib and Sir Syed’s fondness for Kolkata and its cultural moorings deflates the widespread but erroneous assumption that Urdu literature often regurgitates the themes of several well-known Persian and Arabic poets and authors. It also affirms that Urdu literature did not look up to the language of power, but it kept an eye on what was being discussed or written in the languages in different parts of India. In line with its resilience, Urdu turned its attention to Rabindranath Tagore, whose unmatched creative dexterity was reflected in various genres of literature, music, paintings, acting and teaching.

It looks pertinent to mention that Munshi Premchand (1880-1936), who laid the foundation of fiction in Urdu, expressed his deep sense of indebtedness to Tagore for acquainting him with the pulsating art of storytelling much before Tagore won the Nobel Prize. In a letter to Munshi Daya Narian Nigam, editor of Zamana, monthly, Kanpur, Premchand alludes to one of his unfinished stories that owed to Tagore:

“I started writing a fable titled Vikramait ka Tegha; jotted down thirteen pages or so and intend to add five or six more pages. I have been ruminating over the story for many months. I believe I have emulated it successfully. It is not a bad imitation; the plot is entirely original.”(My translation)

In the same letter, he advises the editor to get in touch with Tagore to obtain the painting:

“Zamana has not been carrying good colour photographs for the last two months. Ravi Verma’s paintings are no longer in; why don’t you contact Rabindranath Tagore as he was undoubtedly an exponent of painting (my translation).”

Premchand’s letters, written between 1910 and 1932, are replete with Tagore’s adulatory references, and his name appears twelve times, but one letter surprisingly interdicts him. Sensitive and sympathetic portrayal (having visible traces of patriarchal, patronising attitude) aside, Premchand denounced feminism which was nothing more than a call for providing fundamental human rights to women. He did not spare Tagore on this count. In his letter to Imtiyaz Ali, dated September 14, 1920, he says:

“I want to see literature as a masculine entity. I do not like feminism, no matter how it appears. This is the only reason I read many poems by Tagore and dislike them. It is my natural failing, and I cannot help it.”(My translation)

Exploring similarities between Premchand and Tagore, Abuzar Hashmi, a notable Urdu critic, asserts; ‘it is most likely that Premchand had learnt simplicity, lucidity of expression and depiction of reality from Tagore. He also translated two novels by Tagore into Urdu.

Besides Premchand, a celebrated Urdu poet, Josh Malihabadi (1898-1982), whose sensuous and revolutionary poetry blazed a new trail in Urdu, had cordial relations with Tagore. At his invitation, he had spent six months at Shantiniketan. Josh fashioned a gripping and candid narrative of his stay in his widely acclaimed autobiography, “Yadon ki Baarat”. Terse and compelling account in elegant prose reveals great literary merits and the unpredictable human psyche. The narration oscillates between adulation, objectivity, hostility and envy with equal vehemence. Josh’s anecdotes seem to be an honest effort to understand the literary phenomenon called Rabindranath Tagore. Josh Malihabaadi writes:

“When I returned to Lucknow from Ajmer, I found general admiration for Tagore. I went there to meet him. Looking at me carefully, he asked me in English, “Is it true that I am looking at the face of a young poet? I replied with a bowing head, probably, yes! He inquired about my name. I told my poetic name. Shaking hands with me, he said, ‘It was a pleasant surprise that Sarojini Naidu recited the translation of your poem, The Dawn, yesterday, and I saw you today. Your poem is unmatched; I can describe you as the son of the dawn after listening to it’. After that, he told me that his father was a great scholar of Persian, and a collection of Hafiz was found at his bedside. When I was leaving, he asked me, ‘Is it possible for you to stay at Shantiniketan with me for some time and explain the nuances of Hafiz’s poetry so that I could acquaint myself with the spirit of his poetry?‘. I quite happily accepted his invitation. I reached there with my servant Jugnu and several books. Tagore gave me a rousing welcome and put me in the room of his student Bunty.”

I was immersed in the radical thoughts rescinding mysticism, but Tagore’s poetry went well with me. Had I been Bengali, I would have understood him how he ought to be.

Turning his Tagore’s personality, Josh observes;

“I have spent six months with him, only six months one hence what could I say about him. The most noticeable feature is his truly cosmopolitan nature, he was always high spirited, extremely gentle, sensitive and an admirer of beauty.”

Josh found that the affable personality of Tagore was also riddled with one or two traits that look repugnant; “His penchant for publicity left me completely annoyed. Whenever a foreigner came for his interview, he would sit at a high-up place after getting himself fully spruced up. Ambergris would light up behind him. Fully surrounded by beautiful girls, he would give the interview in such a manner that the interview seeker would get the impression that he was speaking to a divinity.”

This trenchant observation combining wit and sobriety provides insights into the life of Maulana Abul Kalam Azad (1888-1958), whose euphuistic prose opened new vistas upon Urdu prose and was deeply influenced by the florid narration of Tagore.

Geetanjali fired the imagination of many Urdu authors and poets and was rendered into Urdu many times. The translations provided sustenance to two literary movements – Romanticism, and the Progressive writers’ movement in Urdu Tagore’s prose engendered a new genre Adab-e Lateef (light literature) in Urdu prose.

Many novels, plays and short story collections of Tagore appeared in Urdu. Gora and Kabuli Wala got widespread currency in Urdu, and a prominent short story writer Anwar Qamar created his text titled “Kabuli Wale Ki Waps

—The author is Head of the Department, Mass Communication, Aligarh Muslim (AMU), Aligarh.