In 333 B.C. Alexander the Great marched his army into the Phrygian capital of Gordium in modern day Turkey. Upon arriving in the city, he encountered an ancient wagon installed by King Midas in the Second Millennium, its yoke tied with ‘several knots all so tightly entangled that it was impossible to see how they were fastened’.

An oracle had declared that any man who could unravel its elaborate knots was destined to become ruler of Asia. Alexander was instantly seized with an ardent desire to untie the Gordian knot.

After wrestling with it for a time and finding no success, he stepped back from the mass of gnarled ropes and proclaimed, “It makes no difference how they are loosed.” He then drew his sword and sliced the knot in half with a single stroke. A 100-year-old problem was solved with a simple but bold solution.

Global bond yields relatively calm

On the other hand, global rates continue to be well below historical levels in advanced economies with inflation being held down by long-term drags such as ageing, slow productivity growth and technological improvement which are unlikely to change in the medium term.

The pool of bonds with negative yield (borrower receives interest) is still at a whopping $7 trillion compared to $18.3 billion at the start of 2014. Although yields have shown a synchronised pick-up in the last 6 months as G3 central banks are unwinding their unconventional monetary policies, they are expected to remain below historical levels.

In fact, the US yield curve has fallen to the flattest in a decade, with US 10Y/2Y sovereign spread trading at ~0.5per cent compared to its 10 year average of 1.5 per cent due to uncertain outlook on wage growth and long-term inflation.

India vis-a-vis other emerging markets

India’s external vulnerability is substantially lower with strong macro-fundamentals (strong current account, record FX reserves, moderate inflation) and stable political climate which is also reflected in the recent rating upgrade and record FDI/FPI flows.

Total external debt to annual exports is just 1 time which gives us significant cushion even if global growth were to falter while external debt to GNI (includes remittances where India is relatively strong) has in fact reduced to a very stable 20 per cent compared to 2012-14 levels.

Even if we add total government, corporate (non-financial) & household debt which many rating agencies and foreign investors look at, we are one of the few countries which has improved its position in the last 3 years. From a real rate perspective, India continues to offer the highest real yields & sufficient cushion among the larger emerging markets notwithstanding the expected increase in CPI.

In recent years, several countries including Australia, the United States, Japan, France, Italy, Spain, Canada and Switzerland have issued a number of securities maturing in 30 to 70 years. Mexico, Belgium, Austria, Belgium, Ireland have sold 100-year bonds, which are called “century bonds”.

Even Argentina rated B2 by Moody’s, 5 notches lower than India, which has defaulted 7 times on its international debt since its independence, was able to raise a 100-year $2.75 billion bond which received 3.5 into oversubscription.

There could be some opposition in India as well but we should not look at foreign currency borrowing from a position of weakness but one of strength which will reflect our global acceptance as we have built sufficient buffers in the form of high Forex reserves and stable inflation. Just like we welcome FDI flows, we should welcome long-term flows and help diversify our borrowing as well, especially when we want to channelise domestic financing towards private sector.

This will also alleviate RBI’s concerns on market volatility on opening of FPI limits on domestic market as dollar bonds will be outside the purview of domestic market. It will also help preserve the fiscal discipline for future as global bond vigilantes will make sure successive governments maintain macro-stability.

The government and the RBI have done a lot of hard work and swallowed political bitter pills to improve India’s fundamental position in the global market. Now it’s time to reap the benefits.

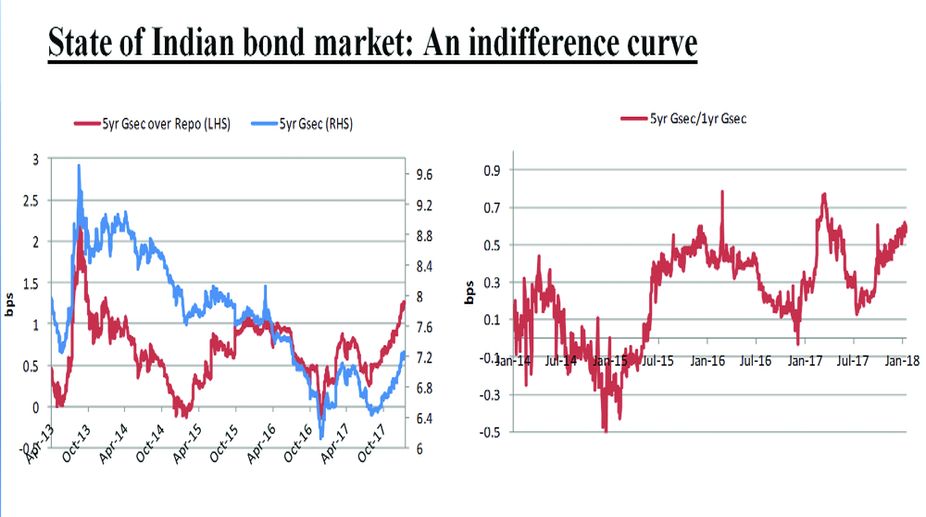

Despite a stable macroeconomic environment, Indian bond yields have risen significantly in the last 6 months with the 5 year Gsec rising from 6.5 per cent in August 2017 to 7.25 per cent in January 2018. While the 10 year benchmark has also moved in a similar direction, it’s equally important to look at the 5-year benchmark. The 3-5 year segment valuation not only reflects rate expectations but systemic liquidity and demand dynamics.

The rise in yields is being attributed to higher government borrowing due to structural reforms like GST, rising inflation expectations compared to FY 2018 & open market sales (17 per cent of gross borrowing) by RBI.

However, one overlooked but important facet is the demand dynamics where demand by financial institutions like insurance/pension/mutual funds has been limited by their inflows and mandates, FPIs are restricted by their limits and the banking system has ended up picking the rest of the tab.

PSU banks especially invariably got sucked into absorbing this excess supply due to high liquidity after demonetisation, limited MSS absorption (`1 lakh crore against average liquidity of 4.5 lakh crore in March 2017) & low credit offtake due to legacy issues..

As liquidity declined, credit picked up and PSU banks had to make higher provisions after the bankruptcy code.

Their incremental risk appetite came down in the face of relentless supply leading to hardening of yields and MTM losses on their existing investment book.

Market demand has gone sour to such an extent that RBI had to partially cancel 2 out of 3 auctions in December 2017/January 2018. The last time RBI had to reject bids in an auction was June 2015.

The current rise in yields on the short end is remarkable when the CPI inflation is expected to be range-bound (FY2019: 4.5-4.8 per cent average), output gap is still negative, current account is stable, FDI/FPI flows are at record high, sovereign rating has been upgraded and government is continuing on the path of fiscal consolidation.

While government has reduced this year’s extra borrowing, the main concern apart from RBI’s hawkish commentary is next year’s borrowing. Even if we assume the Centre will print a fiscal deficit of 3.2 per cent, expected gross market borrowing could be in the range of 6.5-7 lakh crore and state borrowing is expected to be 4.0-4.5 lakh crore which will be difficult to be met by banks.

(The writer is Associate Director in IDFC Mutual Fund, Mumbai)